Like many Muslims, Ahmed Aboutaleb has been disturbed by the angry tenor of the Dutch election campaign. Far-right candidates have disparaged Islam, often depicting Muslims as outsiders unwilling to integrate into Dutch culture.

It is especially jarring for Aboutaleb, given that he is the mayor of the Netherlands’ second-largest city, Rotterdam; fluent in Dutch; and one of the country’s most popular politicians.

Nor is he alone: Dutch Speaker of the House of Representatives Khadija Arib is Muslim, although her Labour Party is expected to lose ground in today’s national elections.

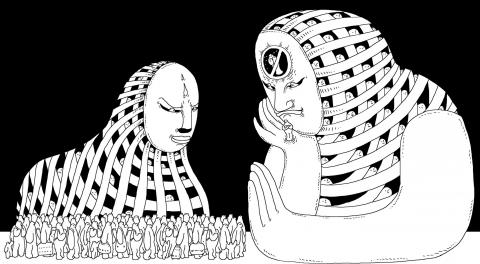

Illustration: Mountain People

The Netherlands also has a burgeoning professional class of Muslims: social workers, journalists, comedians, entrepreneurs and bankers.

“There’s a feeling that if there are too many cultural influences from other parts of the world, then what does that mean for our Dutch traditions and culture?” said Aboutaleb, whose city is 15 percent to 20 percent Muslim and home to immigrants from 174 countries.

Today’s elections begin Europe’s year of political reckoning. The Dutch elections, coming ahead of others in France, Germany and possibly Italy, will be the first test of Europe’s threshold for tolerance as populist parties rise by attacking the EU and immigration, making nationalistic calls to preserve distinct local cultures.

It is an especially striking gauge of the strength of anti-establishment forces that such calls are falling on receptive ears even in the Netherlands, a country that for generations has seen successive waves of Muslim immigration.

If anything, the Netherlands is a picture of relatively successful assimilation, especially when compared with France or Belgium.

In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders, one of the most stridently anti-Muslim politicians in Europe, recently described some Moroccans as “scum.”

His Party for Freedom is expected to be one of three to receive the most votes, challenging the center-right government of Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

If barriers exist, many Muslims — like Aboutaleb, 55, who arrived in this low-lying country from a mountain village in Morocco when he was a teenager, speaking hardly a word of Dutch — say that hard work is nonetheless rewarded.

However, Aboutaleb’s extraordinary success story, and sense that he was given many opportunities by the Netherlands, is more characteristic of an earlier generation.

There is no doubt that religious prejudice is on the rise in response to both the more recent influx of Muslim immigrants and growing fears of terrorism in Europe. Both are readily manipulated by politicians, who promote the idea that there are now so many nonwhite, non-Christians in the Netherlands that Dutch traditions will be lost or obliterated.

However, there is a seed of fact: There are more non-Western migrants or their children in the Netherlands, comprising about 10 percent of the population in a country of about 17 million, but not all of them are Muslim: There are, for example, a number of Indians who are Hindus or Buddhists.

The latest figures released by the Netherlands’ central bureau of statistics show a net increase of 56,000 immigrants in 2015 and 88,000 last year, with the largest number last year, about 29,000, coming from Syria.

The number of municipalities that have populations with 10 percent to 25 percent non-Western migrants doubled between 2002 and 2015, according to the Netherlands Institute for Social Research, a government agency that studies social policy.

A disproportionate amount of crime is committed by young Muslims, especially Moroccan teenagers and young men, but that is also true of immigrants from the Netherlands Antilles in the Caribbean.

And there are many first, second and now third-generation Muslims in the Netherlands who play significant roles in both public life and private work.

“Wilders speaks to a part of Dutch society that feels their Dutch identity is threatened,” said Fouad El Kanfaoui, 28, a banker at ABN Amro in The Hague and a second-generation Moroccan Muslim.

He also serves as the chairman of the Ambitious Networking Society, an organization for young businesspeople, entrepreneurs and those in the arts who are mostly of a Moroccan background.

“The Dutch supermarkets and bakeries are leaving,” he said. “Instead of Hans’ bakery, it’s Muhammad’s bakery. When traditions change it’s difficult; when it’s confronting them personally, it’s challenging.”

Those perceptions make for some stark juxtapositions. Recently, Dutch-Moroccan comedian Anuar Aoulad Abdelkrim was having brunch on one of the main squares in Utrecht when his conversation was interrupted by noise from a rally of the far-right group Pegida. The group, which was founded in Germany, now has a Dutch chapter.

Abdelkrim shook his head and said that “after 15 to 16 years in comedy, I refuse to go on a TV show explaining why a guy with a beard does something that everyone knows is wrong,” referring to militant terrorism.

“Everyone comes to my shows, every religion, every color, a lot of executives,” he said. “Sometimes people come up to me afterward and they say: ‘You know, I’m a little bit racist, I don’t like my neighbors, but I like you.’”

To some extent, that is the Dutch way, Abdelkrim said.

In his neighborhood, a mixture of immigrants and white Dutch people, there was great reluctance initially to welcome the Syrian refugee families whom the government had placed there.

“People said: ‘No, no, no, what do we have to do with them,’ but now it’s a 180-degree turn because people got motivated to help the refugees because they know their story,” he said.

Achraf Bouali, 42, who was born in Morocco, left a diplomatic post to run for parliament in the current election on the slate of D66, the leading left-leaning party. The party has a strong focus on education and the environment and is socially liberal.

He sees the current anti-immigration politics as a product of external factors that have reverberated in the Netherlands: terrorism in Europe; the 2008 financial crisis, which left many Dutch feeling less well off and less secure; and the recent wave of refugees coming to Europe from war-torn regions in the Middle East.

However, part of what gives Muslim politicians like him hope is that in the past many Muslim immigrants have blended quite seamlessly into Dutch society.

“We have been working together in this country for centuries to protect ourselves from the water, building the dikes,” he said. “At the end of the day, there’s a pragmatism and a spirit of working together to solve our problems — and there are problems.”

In the 1990s, tens of thousands of Muslims came from Bosnia during the civil wars in the former Yugoslavia. Afghans came during their country’s civil war and the Taliban period. Both groups have integrated well.

Before them, large numbers of Indo-Dutch immigrants came in the 1940s from what was then Dutch parts of Indonesia. Moroccans and Turks came for jobs in the 1960s and 1970s.

The politics are less hospitable now, said Marianne Vorthoren, the director of SPIOR, a group that trains teachers to give Islamic religious instruction in Dutch schools.

Vorthoren, who converted to Islam and is married to a Turkish doctor, said that in 2015, her organization had gathered 174 reports of hate crimes against Muslims — more than three times the number collected by the government.

She said the current debate had become overly focused on whether Muslims were “integrated enough” or “assimilated enough,” crowding out actual dialogue.

“When you tell people their problem is their identity, it’s who they are, there’s no room to talk about real issues like forced marriage, radicalization, domestic violence,” she said, referring to the criticisms some Dutch make of Muslims.

The modest Schilderswijk neighborhood in The Hague, which has been the scene of riots in the past, has become synonymous in the Dutch media with the troubled Muslim part of town.

Jan Kok, a career police inspector in The Hague, has become a sort of chief cultural officer for the police force and works with three station houses around the city to improve relations with Muslims.

He created a mandatory course for new police recruits to teach them about working with minorities and a course for those already on the force.

He said many of the young immigrant men “grow up without a father, without respect for the police, for the rules in the Netherlands.”

However, he is empathetic to their deeper struggle.

“They have a problem with their identity: Am I a Dutchman, am I a Moroccan, am I both?” he said. “Everyone needs to belong somewhere — to a church, to a mosque — and most of them don’t have that.”

“And then you have Wilders and Rutte, the prime minister, saying: ‘You don’t like it here, then go away,’ but these boys were born here. Where are they going to go?” he added.

On the outskirts of Amsterdam, a group of young Muslim men gather most nights at a community center called the Hood, where they came as teenagers and now act as volunteer mentors to encourage younger children in the neighborhood to stay out of trouble.

Most of the young men who volunteer found jobs out of high school — but only after long searches. They say they feel trapped because even if they wanted to study to be lawyers or doctors or have an advanced degree, they could not afford it.

“A lot of people in this neighborhood have to work to help their families, they can’t stay in school,” said Zaid Belmahdi, 19, who got his first job interview only after sending out 131 applications.

Yassir Aknin, 21, has training in information technology, but he said nine out of 10 prospective employers will not even see him because of his Muslim name.

“You have to learn to live with it, you have to be strong,” he said, as his friends around the table nodded in agreement. “But other guys don’t have this and it happens twice and they get depressed and stop trying.”

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,