On paper at least, Asian-Americans seem like perfect US Republicans. Many are small-business owners. Their communities tend to be more culturally conservative. And a lot of them, having fled oppressive communist governments, found comfort in the Republican Party’s aggressive anti-communist policies.

However, in what could be a significant realignment of political allegiance, Asian-Americans are identifying as US Democrats at a quicker pace than any other racial group. And many Republicans worry this election will only accelerate that trend, damaging their party for years to come with what is now the fastest-growing minority in the US.

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump is not helping. His attacks on Chinese — which he has sometimes delivered in a crude, mocking accent — are a feature of his populist campaign. He has suggested cutting off immigration from the Philippines, citing fears that the longtime US ally poses the same national security threat as countries like Syria and Afghanistan.

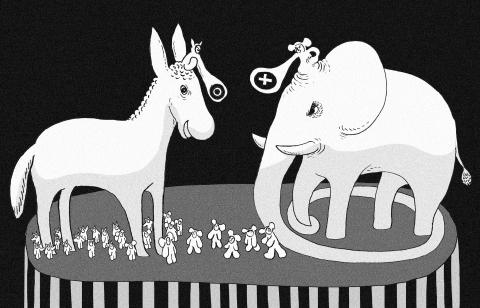

Illustration: Mountain People

Trump’s talk of deporting millions of undocumented immigrants has also stirred up painful memories among a group that has been singled out under US law before, whether by the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred the immigration of Chinese laborers until 1943, or by the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

“It’s like we’re going back in time,” said Marc Matsuo of Las Vegas, who grew up in Hawaii with parents of Japanese ancestry and recalled how his family used to feel uncomfortable expressing their heritage, to the point they would not speak Japanese.

He now helps register Asian-Americans to vote.

“I was always brought up that you don’t talk about religion, you don’t talk about politics. Not anymore,” he said.

Though Asian-Americans are still just 4 percent of the overall eligible voting population, their political power is concentrated in important swing states like Nevada and Virginia, where both parties have been building on their efforts to reach out.

In and around Las Vegas, home to one of the US’ largest Asian populations, this means printing campaign leaflets in Korean, having a Vietnamese translator on standby at speeches, publishing opinion-editorial articles in the local Filipino newspaper and hiring employees who know enough Mandarin to recruit voters at the Chinatown seafood market.

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton’s campaign has a resident staff member in Las Vegas dedicated to Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders. Staff members and volunteers there speak Chinese, Korean, Hindi and Tagalog, a Filipino language.

The campaign has recently been conducting native language training on how to use voting machines in a local Chinese cultural center. Volunteers are sent to court supporters in Buddhist temples.

Although Trump’s campaign last week announced a new Asian Pacific American Advisory Committee, a Republican National Committee spokesman, Ninio Fetalvo, said Trump’s outreach to Asian-American voters had been coordinated until now mainly through two staff members at the party’s Washington headquarters. The party, he added, has also printed materials in a variety of Asian languages in cities like Las Vegas.

Republicans’ difficulties with Asian-Americans are similar to those the party has faced with most minority groups. A sense that the party is hostile to immigrants and minorities has driven more Asian-American voters into the Democratic Party lately, political scientists and community leaders said.

And if Republicans do not make more of an effort, those voting shifts could harden, just as Hispanics’ voting patterns have.

“What we see now are some early indications that people who either leaned toward the Democratic Party or did not identify with either party are now starting to identify as Democrats,” said Karthick Ramakrishnan, a professor of political science at the University of California, Riverside.

“This is still a group that is making up its mind, but it should be concerning to the Republican Party that you’re starting to see this crystallization,” he said.

A national survey in the spring by Asian and Pacific Islander American Vote, a nonpartisan research group, showed “a significant leftward shift” since 2012 among Asian-American registered voters, with 47 percent now identifying with the Democratic Party, compared with 35 percent in 2012. Fifteen percent identified as Republican.

In 1992, the year national exit polls started reporting Asian-American sentiment, the group leaned Republican, supporting then-president George H.W. Bush over then-Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton 55 percent to 31 percent.

However, by 2012, that had reversed. Asian-Americans overwhelmingly supported President Barack Obama over then-Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney — 73 percent to 26 percent, almost the same margin by which Hispanics favored Obama.

A Pew Research Center report released last month showed that Asian-Americans have since 2008 embraced the Democratic Party at a faster rate than any other ethnic group.

Still, many Republicans believe that the damage is reversible and see Asian-Americans’ political identity as still very young and malleable. For example, among many Asian-Americans, there is a tendency to be less forgiving on illegal immigration, which is sometimes seen — unfairly or not — as an issue specific to Latinos.

Lanhee Chen, who was Romney’s policy director in 2012, said the effect of Trump’s harsh talk on immigration could be more muted with Asian-Americans than it is with other minorities.

“Trump has not been helpful,” Chen said. “Now is it as directly harmful as it would be to Latinos? I don’t think so.”

As Asian-Americans have replaced Hispanics as the nation’s fastest growing racial group, Nevada has become the center of their emerging political class. Asian-Americans are now about 7 percent of the electorate in the state, a figure that is expected to double by 2060.

Democrats and Republicans have concluded that winning in closely divided Nevada requires performing strongly among Asian-Americans: Republican Senator Dean Heller carried Asian-Americans when he narrowly won in 2012. And Harry Reid, the state’s long-serving Democratic senator who is retiring, performed even better with them than he did among Hispanics in his 2010 election.

None of which is lost on the two candidates vying to succeed Reid: US Representative Joe Heck, the Republican, employs an aide who speaks Mandarin and has made Kamayan dinners — traditional Filipino banquets — as much a campaign staple as marching in parades.

And Catherine Cortez Masto, the Democrat, grew up in the Las Vegas neighborhood that has since become the city’s Chinatown, with Korean barbecue restaurants, Vietnamese noodle bars, foot spas and Chinese arches. When she attended a lunar celebration last month, she spoke in English as someone translated her words into Vietnamese.

As much as Trump’s positions seem to be driving Asian-Americans into the Democratic Party, the group defies easy political categorization. Many Koreans are evangelical Christians. Filipinos overwhelmingly belong to the Roman Catholic Church. Many Vietnamese who emigrated during the war identify closely with the Republican Party’s anti-communism.

“In general, Asian values are very much in line with Republican values: family, education, the country needs to be stable,” said James Yu, a member of the Las Vegas Asian Chamber of Commerce, which has endorsed Heck in the Senate race.

Notably, it has not backed Trump.

By next month, about 9.3 million Asian-Americans will be able to vote nationally, or 4 percent of the eligible voting population. That is up from 8 million in 2012. And that growth has spawned new civic organizations, like the nonpartisan Asian Community Development Council in Las Vegas, which aims to boost the group’s low voter turnout. Only 47 percent of eligible Asian-Americans voted in 2012.

Vida Chan Lin, the group’s founder, said that her message each time she goes out to register Asian-Americans to vote — in casinos’ employee lunchrooms, in Chinatown shopping malls and at employee orientations for businesses like the Panda Express fast-food chain — is that they have to harness the power of their growing numbers.

“We’ve got to get them to vote,” Lin said in her office, which was humming with volunteers planning registration drives, as well as follow-up calls as reminders to vote.

One positive consequence of Trump’s divisiveness, she said, was that interest in the election is like nothing she has ever seen. And the chatter about it follows her everywhere.

“When I went to China, they were talking about it,” she added.

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

“Can you tell me where the time and motivation will come from to get students to improve their English proficiency in four years of university?” The teacher’s question — not accusatory, just slightly exasperated — was directed at the panelists at the end of a recent conference on English language learning at Taiwanese universities. Perhaps thankfully for the professors on stage, her question was too big for the five minutes remaining. However, it hung over the venue like an ominous cloud on an otherwise sunny-skies day of research into English as a medium of instruction and the government’s Bilingual Nation 2030