The three years since the onset of the credit crunch have seen the cost of borrowing for households soar despite interest rates falling to a record low and the banks returning to bumper profitability.

Young people and first-time buyers are bearing the brunt of the crunch with a much higher premium charged to those who lack large deposits for mortgages. Figures from Countrywide, Britain’s largest estate agency, reveal that the most common mortgage taken out by its customers last month had a starting interest rate of 6.49 percent.

That is almost 6 percentage points above the Bank of England’s historic low rate of 0.5 percent, but while base rates have fallen over the past three years, the cost of borrowing has headed in the opposite direction, fast.

Personal loans were selling at an interest rate of 6.8 percent in August 2007, according to Moneyfacts. Today the best rate is 8.8 percent — but only for those with an “excellent” credit record. If the borrower has a “fair” credit rating, then the best rate is an extraordinary 53.9 percent.

The average credit card three years ago charged 16.5 percent, but that rate has not been seen since. Moneyfacts says now the average credit card charges 18.6 percent — and applicants who have only a middling credit record are more likely to be offered rates of 30 to 35 percent.

The best two-year fixed rate mortgage in August 2007 was a 5.39 percent deal from Alliance & Leicester, available on a deposit of just 5 percent, but less than a year later, Alliance & Leicester was taken over by Santander and low-deposit mortgages went the same way. Of the few still around, the interest rate charged is 7 percent or more. Those mortgage customers of Countrywide are paying 6.49 percent because, perhaps not surprisingly, they can only find a 10 percent deposit.

According to Moneyfacts, the margin on five-year fixed-rate mortgages at six leading lenders increased from 2.39 points to 3 points in 12 months, raising the cost of a £200,000 (US$313,000) loan by £1,200 a year, the Sunday Times reported.

The ultra-low deals that appear at the top of best-buy tables are reserved for new buyers who can stump up a 30 percent or even 40 percent deposit. Most people on an average income struggle to raise a 10 percent deposit, and for them, talk of record-low interest rates is a sham. They might consider themselves lucky even to be offered a loan at 6.49 percent. Ray Boulger, of mortgage brokers John Charcol, says he knows of one major bank that turns down 90 percent of people who apply for a 90 percent loan.

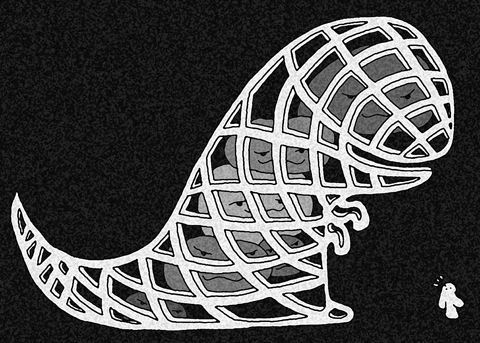

The decade of easy money came to an abrupt halt in August 2007, but what has emerged since is a divided Britain in which young adults are paying the price of the credit crunch, while their parents have landed a get-out-of-jail-free card. New borrowers are either locked out of the market or face permanently higher loan costs.

The grim mathematics of new capital adequacy requirements for banks mean that cheap and plentiful loans of 90 percent or more for first-time buyers will never return.

Under the new international rules — what’s known as “Basel II” — banks have to set aside a much higher amount of capital for higher-risk lending, such as a 90 percent loan-to-value mortgage.

“Banks now have to set aside six or seven times as much capital for a 90 percent loan compared with a 60 percent loan,” Boulger said.

It certainly explains why banks can charge sub-3 percent interest on 60 percent mortgages, but want an interest rate of more than 6 percent on a 90 percent deal.

“And this is not going to go away in five or even 10 years’ time. If anything, Basel III is likely to be even more onerous,” Boulger says.

The long-term implications are indeed worrying. Well-off parents will be able to access the equity in their homes and use the money to help their offspring put down a deposit on their first home, but the children of low-income families may find themselves permanently excluded.

“What’s happening with deposits will tend to accelerate divides in society,” Boulger says.

The lending landscape has changed dramatically, possibly for many years to come. A collapse in wholesale funding was at the heart of the credit crunch — banks such as Northern Rock, at one time the source of 25 percent of all new mortgages in Britain, found they could no longer tap the wholesale market. There are few signs of that funding returning. Meanwhile, building societies (savings and loans mutual societies) have retreated massively and are only prepared to lend out what they bring in from their savers.

In August 2007, HSBC barely featured as a mortgage lender and Santander was still getting to grips with its purchase of Abbey. Now they are the two biggest gross lenders in what is a much-shrivelled mortgage market.

“HSBC has played a very clever game. In 2007, when mortgage margins were incredibly skinny, they were lending very little, but today they can offer market-leading products at 2 to 3 percent that still give them a better margin than in 2007,” Boulger said.

However, exhortation by the British Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne to make the banks lend more is also likely to fall on deaf ears. By some estimates the UK banks have to find an astonishing £800 billion over the next few years. They owe about £180 billion under the emergency Special Liquidity Scheme, introduced in 2008 and designed to run until 2012. There is a further £200 billion in another emergency vehicle, the Credit Guarantee Scheme, designed to run until 2014, and as much as £400 billion in other securities that will need to be repaid or refinanced. It’s not an environment in which retail credit will be eased or extended.

Kevin Mountford, banking expert at moneysupermarket.com, says the phony war period of the credit crunch is firmly over.

“Technically, when we went into recession, most consumers didn’t really feel like it, as it wasn’t hurting them, but credit has been getting tougher ever since,” he said.

Not only do borrowers now have to fulfil much tighter income and affordability criteria, the credit crunch has also spelled the end for the “rate tarts” who moved mortgages frequently to take advantage of easy money.

“Banks are now much more likely to turn you down if you are deemed to be a rate chaser. They are much better at determining whether you are going to be a profitable customer or not,” Mountford said.

An ongoing review of the mortgage market ordered by the Financial Services Authority (FSA) will further tighten credit conditions. The FSA’s early findings reveal how lax borrowing had become — with more than half of all mortgages granted without proper checks on the borrower’s salary or ability to repay. It is now minded to ban so-called “fast track” mortgages in which a borrower’s details are only briefly checked and force borrowers to take out repayment rather than cheaper interest-only mortgages. The self-employed will also face enormous challenges finding mortgages, with “self-cert” loans — where borrowers attest but don’t need to prove that they can afford the repayments — facing the axe.

However, although the credit crunch has dramatically altered the borrowing landscape, the forecast meltdown in the property market has not materialized — for now at least. Housing prices fell, although by less than many experts predicted and in some parts of the country, such as central London, they have recovered to peak levels. Repossessions have also been more benign than anticipated. The Council of Mortgage Lenders expected 75,000 repossessions last year, but in the event there were only 48,000, which Boulger attributes to the decision to allow income support for mortgage interest after three months rather than six.

The slow-burn victims of the credit crunch have been savers, particularly the elderly who rely on deposit accounts to provide an income. Before the credit crunch, savers could find rates as high as 7 percent, but they went the same way as Icesave, the Iceland owned Internet bank that offered generous interest rates, but collapsed in 2008.

Typical rates today are closer to 2.5 to 3 percent. Future pensioners will also suffer — as millions of employees have been shifted to “defined contribution” plans, where payout values are dependent on the vagaries of the stock market. When these schemes mature, pensioners will have to buy an annuity with all or part of the proceeds built up. If the recession results in interest rates remaining low for years, as many in the City, London’s financial district, are now predicting, then annuity rates will also remain at paltry levels. Many employees will simply not be able to afford to retire. Working into our 70s may be the true legacy of the credit crunch.

The slump in value of newly constructed apartments triggered by the credit crunch has left many young professionals facing financial ruin.

At the height of the property boom, Euan Robertson, a 31-year-old information technology consultant, put down a £45,000 deposit — “my life savings,” he says — on a new £450,000 three-bed apartment in London’s Docklands. Before signing up, he was prudent enough to make sure he could get a mortgage for the remaining 90 percent, which was valid until March last year, by which time the apartments would be completed. However, things started to unravel when, in December 2008, he obtained a valuation that indicated the flat had plunged in value to £340,000.

No lender would be willing to advance him £405,000 on a property valued at significantly less than that and he could only access a loan of £270,000 against the property, but the developer, Berkeley Homes, insisted he stump up the full purchase price agreed in the initial contract. It left him in the near-impossible position of having to find more than £100,000 to plug the gap.

Robertson said he was so worried that “I couldn’t sleep and couldn’t eat.”

He was one of dozens of buyers caught out who joined the berkeleyhomescollective.com action group. He was served with legal papers by Berkeley in June last year, but the case did not reach court.

“An agreement has been reached, the details of which are confidential,” he said.

Today he’s living in a one-bed apartment in Greenwich.

“We are hopeful of starting a family in the next 12 months,” he said. “We’ve tried to put this behind us and enjoy where we live now, despite the constraints of space. We’ve been married two years now and I think having survived this together, we can survive anything.”

A check on the Land Registry shows the Berkeley flat originally valued at £450,000 was later sold for £350,000.

“It remains Berkeley Homes’ position that purchasers cannot be released from contracts or offered price reductions as to do so would be unfair to those buyers who have been able to complete and who were faced with the same issues,” a spokesman for Berkeley Homes said.

“Berkeley Homes stated at the outset that they were willing to meet with all customers who were having difficulty in completing so that the customer could provide full financial disclosure. As a result of this process, Berkeley Homes have been able to resolve the majority of these cases without the need to take legal action,” he said. “Mr Robertson’s case has been resolved without the need for legal action.”

In the past month, two important developments are poised to equip Taiwan with expanded capabilities to play foreign policy offense in an age where Taiwan’s diplomatic space is seriously constricted by a hegemonic Beijing. Taiwan Foreign Minister Lin Chia-lung (林佳龍) led a delegation of Taiwan and US companies to the Philippines to promote trilateral economic cooperation between the three countries. Additionally, in the past two weeks, Taiwan has placed chip export controls on South Africa in an escalating standoff over the placing of its diplomatic mission in Pretoria, causing the South Africans to pause and ask for consultations to resolve

An altercation involving a 73-year-old woman and a younger person broke out on a Taipei MRT train last week, with videos of the incident going viral online, sparking wide discussions about the controversial priority seats and social norms. In the video, the elderly woman, surnamed Tseng (曾), approached a passenger in a priority seat and demanded that she get up, and after she refused, she swung her bag, hitting her on the knees and calves several times. In return, the commuter asked a nearby passenger to hold her bag, stood up and kicked Tseng, causing her to fall backward and

In December 1937, Japanese troops captured Nanjing and unleashed one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century. Over six weeks, hundreds of thousands were slaughtered and women were raped on a scale that still defies comprehension. Across Asia, the Japanese occupation left deep scars. Singapore, Malaya, the Philippines and much of China endured terror, forced labor and massacres. My own grandfather was tortured by the Japanese in Singapore. His wife, traumatized beyond recovery, lived the rest of her life in silence and breakdown. These stories are real, not abstract history. Here is the irony: Mao Zedong (毛澤東) himself once told visiting

When I reminded my 83-year-old mother on Wednesday that it was the 76th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, she replied: “Yes, it was the day when my family was broken.” That answer captures the paradox of modern China. To most Chinese in mainland China, Oct. 1 is a day of pride — a celebration of national strength, prosperity and global stature. However, on a deeper level, it is also a reminder to many of the families shattered, the freedoms extinguished and the lives sacrificed on the road here. Seventy-six years ago, Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東)