As the captains of business and industry meet in Davos for the World Economic Forum, the devastation caused by the recent earthquake in Haiti will be near the top of their agenda. It should be, for there is much they can do to help.

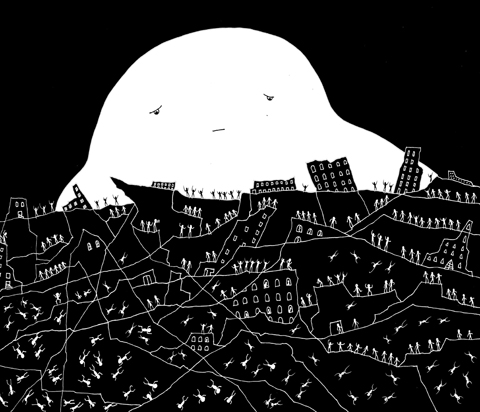

Haiti was in dire straits even before the earthquake struck. Rapid population growth, coupled with political and social turmoil, helped make Haiti the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere. Right now, international relief efforts in Haiti are rightly focused on the country’s urban areas, which suffered most in the earthquake. But when rebuilding starts, rural areas must not be overlooked.

Many of those who have lost their homes and jobs in Port-au-Prince and other Haitian cities will likely return to rural communities where they have family. This will put pressure on the rural economy and place more strain on areas already grappling with meager resources.

Agriculture plays a vital role in Haiti’s economy, yet the country does not produce enough food to feed its people. Some 60 percent of the food Haitians need, and as much as 80 percent of the rice they eat, is imported. Sustainable agricultural development is essential to improving the country’s prospects for long-term economic and food security.

The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) has seen first-hand how investing in agriculture can help people recover from natural disasters. Our experience in developing countries tells us that investments in agriculture can be twice as effective in reducing poverty as similar investments in other sectors.

Less than two years ago, Haiti was devastated by a hurricane that caused about US$220 million in damage to food crops at a time when the population was already struggling to feed itself because of high world food prices.

IFAD funded a program to kick-start food production. The 2008 winter planting yielded US$5 million in bean crops, helping to improve food security and the incomes of poor farmers.

While the crisis in Haiti is a major setback in achieving increased food production, it should not be a stop sign on the path to long-term development. The challenge is to ensure that earlier efforts are not lost, and that recovery includes a push toward sustainable agricultural production systems for Haiti.

One group now rising from the rubble is Fonkoze, a microfinance organization operating predominantly in rural Haiti. With assistance from IFAD’s multi-donor Financing Facility for Remittances, Fonkoze purchased satellite phones and diesel generators in 2007, and began delivering remittance services in rural areas where basic infrastructure is often weak or lacking.

Only today is the true value of that investment coming to light. Fonkoze was back in operation only days after the earthquake. Remittances transferred through Fonkoze are free, giving recipient families in Haiti vital resources to meet short-term needs while encouraging long-term development.

More than US$1.9 billion was sent to Haiti in 2008 through remittances, more than official development assistance and foreign direct investment combined, with more than half of these funds going directly into the hands of families in rural areas.

In Davos I will highlight for the CEOs and business leaders the mutual benefits of forming partnerships with small producers. Much-needed capital investment can enable smallholder farmers to provide the private sector with a sustainable supply of high-quality agricultural produce.

Indeed, smallholder farmers are often extremely efficient producers per hectare and can contribute to a country’s economic growth and food security. For example, Vietnam transformed itself from a food-deficit country to the second-largest rice exporter in the world by developing its smallholder farming sector. As a result, poverty fell from 58 percent in 1979 to less than 15 percent today.

In Haiti, and in developing countries around the world, smallholder farmers can contribute to food security and economic growth just as they did in Vietnam. But they cannot do so without secure access to land and water — as well as to rural financial services to pay for seed, tools and fertilizer. They also need roads and transportation to get their products to market, and technology to receive and share the latest market information on prices. Above all, they need a long-term commitment to agriculture from their own governments, the international community and the private sector, backed up by greater investment.

The productive capacity of Haiti’s small farmers will be crucial in helping the country to overcome this crisis and avert severe food shortages. That is why Haiti needs the private sector now more than ever — to help rebuild both the country and the livelihoods of poor rural people.

Indeed, the private sector has a pivotal role to play in rural development, not just in Haiti but throughout the developing world. But public-private partnerships must be backed up with the right policies and support for rural communities so that poor rural people can increase food production, improve their lives and contribute to greater food security for all.

Organizations like IFAD can help link the private sector and smallholder farmers. We can support investments that expand the productive potential of the smallholder sector in the developing world by helping investors reduce their risks, and by assisting smallholder farmers in accessing new financing and markets through private-sector partnerships.

Klaus Schwab, the founder and chairman of the World Economic Forum, has said that this year’s Davos meeting should be used to “solicit commitments in practical help for relief of the continued pain of Haiti’s people, and particularly for the reconstruction of Haiti.”

In Davos, I will work to ensure that the interests of the world’s smallholder farmers — in Haiti and in developing countries around the world — are represented.

Kanayo F. Nwanze is president of the International Fund for Agricultural Development, an international financial institution and a specialized agency of the UN.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Father’s Day, as celebrated around the world, has its roots in the early 20th century US. In 1910, the state of Washington marked the world’s first official Father’s Day. Later, in 1972, then-US president Richard Nixon signed a proclamation establishing the third Sunday of June as a national holiday honoring fathers. Many countries have since followed suit, adopting the same date. In Taiwan, the celebration takes a different form — both in timing and meaning. Taiwan’s Father’s Day falls on Aug. 8, a date chosen not for historical events, but for the beauty of language. In Mandarin, “eight eight” is pronounced

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

It is difficult to think of an issue that has monopolized political commentary as intensely as the recall movement and the autopsy of the July 26 failures. These commentaries have come from diverse sources within Taiwan and abroad, from local Taiwanese members of the public and academics, foreign academics resident in Taiwan, and overseas Taiwanese working in US universities. There is a lack of consensus that Taiwan’s democracy is either dying in ashes or has become a phoenix rising from the ashes, nurtured into existence by civic groups and rational voters. There are narratives of extreme polarization and an alarming