What is China playing at on climate change? That may be the most important question in the world right now, thanks alone to its status as the world’s biggest producer of greenhouse gases. But what Beijing is — or is not — prepared to do will also determine whether the rest of the world can reach a deal on combating global warming that is worth the paper it’s written on.

So it is hardly surprising that reading the Chinese approach has become the latter-day equivalent of Cold War Kremlinology. Britain alone has more than 20 diplomats in Beijing devoted to monitoring and nudging the Chinese position ahead of December’s UN Copenhagen summit. The US has twice as many.

A flying visit to Beijing (3.9 tonnes of carbon dioxide to offset, before you ask) does not fill you with optimism about the prospects for a deal. For some months now, the mood music from China has been distinctly upbeat: a massive renewable energy drive that could see it surpass Europe’s challenging targets for clean power by 2020, a climate change resolution passed for the first time by the country’s top legislative body, the beginnings of a public debate about when Chinese emissions should peak and begin to fall. Beijing even retained London public relations firm Freuds to try to polish its image on the issue.

But at a conference on reporting climate change last week, senior Chinese scientists and negotiators were in an altogether less emollient mood. The official Chinese position is snappily summarized as “shared burden, differentiated responsibilities,” which roughly translates as “We’re all in the same boat but it’s your fault that it’s taking on water, so you’d better do most of the baling.”

Both publicly and privately, Chinese officials seemed at pains to emphasize just how differentiated those responsibilities should be.

“The developed countries have the money, they have the technology and they think it’s an important issue,” one told me. “So why don’t they do something about it?”

A leading UK government adviser has sounded another disconcerting note: China will not sacrifice economic growth to prevent the world from warming by more than 2oC, the threshold beyond which scientists warn we could face disastrous effects.

European diplomats say they have noticed a hardening of the Chinese position during the summer.

“In the past they used to refer to rich countries cutting their emissions by between 25 percent and 40 percent [by 2020],” one said. “Now they only talk about 40 percent.”

Some speculate that it is little more than pre-summit gamesmanship designed to increase pressure on developed countries desperate for a deal.

But it may also reflect a deeper ambivalence about the issue within the Chinese leadership, the diplomat suggested. “They are caught between a fairly recent understanding that climate change is real, and going to do them real damage, and the competing idea that they don’t fully believe that it’s possible for industrial economies to grow without producing lots of carbon.”

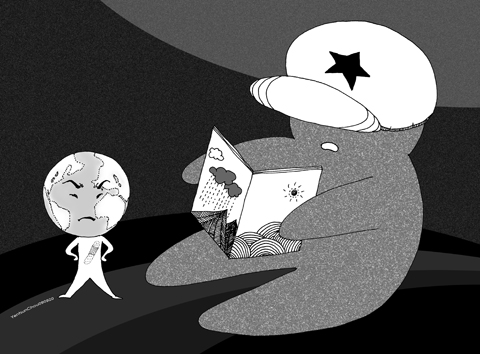

Understanding China’s approach to climate change involves negotiating a number of apparent contradictions. The country that insists it can only begin to tackle its emissions with the help of Western technology and cash is the same one that is spending billions on an ambitious space program, an industrial behemoth intensely proud of its technological prowess.

Meanwhile, China is — as my colleague Jonathan Watts puts it — on course to become “both a green superpower and a black superpower,” that is, simultaneously the world’s green energy giant and its carbon villain.

One Western expert who advises the Chinese on climate policy says the messages from Beijing may not be as contradictory as they seem. China’s talk of decarbonizing is genuine, he says.

“They are bloody serious about this. Their planning is more advanced than anywhere in the world,” he says.

At the same time, Beijing is determined to make the rich countries cut deeper and hand over more technology and cash to developing nations.

Some of this may have more to do with strategic powerbroking than climate change. According to the senior diplomat, China’s aim is to emerge from Copenhagen as the protective uncle that brings home the bacon for the developing nations — which just happen to have a lot of the resources that China needs to fuel its continued economic growth.

But there are less calculating reasons why most Chinese do not consider carbon dioxide emissions the burning issue that we do — they are more worried about the noxious pollutants they face every day. At the Beijing conference a Chinese journalist pointed out that there are 20,000 chemical plants along the course of the Yangtze.

A year or so ago I asked a leading Chinese environmentalist why he was not making more noise about greenhouse gas emissions.

“Because I’m more concerned about whether my son is going to be able to breathe in the morning,” he replied.

No one is expecting Beijing’s negotiators to undergo a Damascene conversion during the late nights of cajoling and compromise in Copenhagen. Instead, it is hoped that China will make a unilateral move in the run-up to the summit, probably spelling out targets to cut its carbon intensity (the amount of greenhouse gases produced per unit of GDP, rather than total emissions) in its next five-year plan. This would theoretically allow China to continue to enjoy the economic growth it says it is entitled to while beginning to move in the right direction.

Then the hard wrangling will switch to the question of how binding any such commitments are. Too strong and Beijing will balk at them; too weak and the deal will look toothless in Washington, London and Berlin.

What does all this mean for those of us trying to decide whether to do our own humble bit to reduce carbon dioxide emissions? The relentless rise of Chinese emissions is often cited as a reason why small-scale unilateral efforts, or even large-scale ones in small countries like Britain, are pointless. If the new power plants that China is building between now and 2020 alone will produce about 25 billion tonnes of carbon over their lifetime, what is the point of my saving 1 tonne by not flying to Spain on holiday?

The answer is that small signals can matter, even to very big countries. Again and again last week I heard Chinese officials bemoan the failure of the West to lead by example on tackling emissions. There had been no shortage of targets, they complained, but precious little action.

After one session with a group of Chinese science journalists, one young reporter approached me looking quite angry. How could Westerners tell Chinese people that they would have to make sacrifices in future to tackle climate change? “And how are you getting to the airport — by taxi or on the Airport Express?”

The government and local industries breathed a sigh of relief after Shin Kong Life Insurance Co last week said it would relinquish surface rights for two plots in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投) to Nvidia Corp. The US chip-design giant’s plan to expand its local presence will be crucial for Taiwan to safeguard its core role in the global artificial intelligence (AI) ecosystem and to advance the nation’s AI development. The land in dispute is owned by the Taipei City Government, which in 2021 sold the rights to develop and use the two plots of land, codenamed T17 and T18, to the

Taiwan’s first case of African swine fever (ASF) was confirmed on Tuesday evening at a hog farm in Taichung’s Wuci District (梧棲), trigging nationwide emergency measures and stripping Taiwan of its status as the only Asian country free of classical swine fever, ASF and foot-and-mouth disease, a certification it received on May 29. The government on Wednesday set up a Central Emergency Operations Center in Taichung and instituted an immediate five-day ban on transporting and slaughtering hogs, and on feeding pigs kitchen waste. The ban was later extended to 15 days, to account for the incubation period of the virus

The ceasefire in the Middle East is a rare cause for celebration in that war-torn region. Hamas has released all of the living hostages it captured on Oct. 7, 2023, regular combat operations have ceased, and Israel has drawn closer to its Arab neighbors. Israel, with crucial support from the United States, has achieved all of this despite concerted efforts from the forces of darkness to prevent it. Hamas, of course, is a longtime client of Iran, which in turn is a client of China. Two years ago, when Hamas invaded Israel — killing 1,200, kidnapping 251, and brutalizing countless others

Art and cultural events are key for a city’s cultivation of soft power and international image, and how politicians engage with them often defines their success. Representative to Austria Liu Suan-yung’s (劉玄詠) conducting performance and Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen’s (盧秀燕) show of drumming and the Tainan Jazz Festival demonstrate different outcomes when politics meet culture. While a thoughtful and professional engagement can heighten an event’s status and cultural value, indulging in political theater runs the risk of undermining trust and its reception. During a National Day reception celebration in Austria on Oct. 8, Liu, who was formerly director of the