During last year’s presidential campaign, US President Barack Obama distinguished himself on the economics of climate change, speaking far more sensibly about the issue than most of his rivals. Unfortunately, now that he is president, Obama may sign a climate bill that falls far short of his aspirations. Indeed, the legislation making its way to his desk could well be worse than nothing at all.

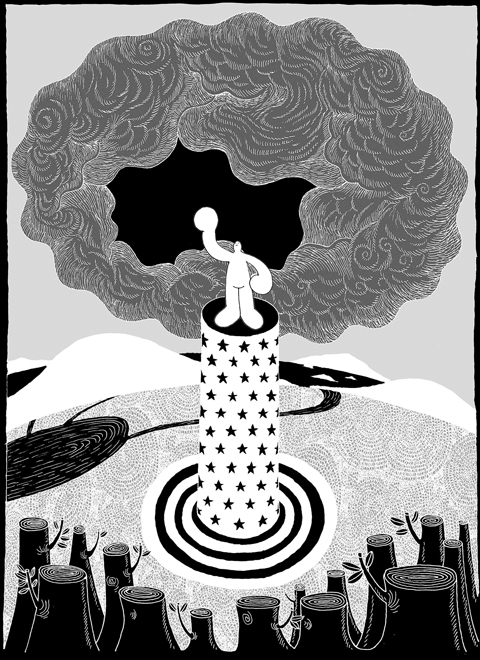

Let’s start with the basics. The essential problem of climate change, scientists tell us, is that humans are emitting too much carbon into the atmosphere, which tends to raise world temperatures. Emitting carbon is what economists call a “negative externality” — an adverse side effect of certain market activities on bystanders.

The textbook solution for dealing with negative externalities is to use the tax system to align private incentives with social costs and benefits.

Suppose the government imposed a tax on carbon-based products and used the proceeds to cut other taxes. People would have an incentive to shift their consumption toward less carbon-intensive products. A carbon tax is the remedy for climate change that wins overwhelming support among economists and policy wonks.

When he was a candidate, Obama did not exactly endorse a carbon tax. He wanted to be elected, and embracing any tax that hits millions of middle-class voters is not a recipe for electoral success. But he did come tantalizingly close.

What Obama proposed was a cap-and-trade system for carbon, with all the allowances sold at auction. In short, the system would put a ceiling on the amount of carbon released, and companies would bid on the right to emit carbon into the atmosphere.

Such a system is tantamount to a carbon tax. The auction price of an emission right is effectively a tax on carbon. The revenue raised by the auction gives the government the resources to cut other taxes that distort behavior, like income or payroll taxes.

So far, so good. The problem occurred as this sensible idea made the trip from the campaign trail through the legislative process. Rather than auctioning the carbon allowances, the bill that recently passed the House would give most of them away to powerful special interests.

The numbers involved are not trivial. From Congressional Budget Office estimates, one can calculate that if all the allowances were auctioned, the government could raise US$989 billion in proceeds over 10 years. But in the bill as written, the auction proceeds are only US$276 billion.

Obama understood these risks. When asked about a carbon tax in an interview in July 2007, he said: “I believe that, depending on how it is designed, a carbon tax accomplishes much of the same thing that a cap-and-trade program accomplishes. The danger in a cap-and-trade system is that the permits to emit greenhouse gases are given away for free as opposed to priced at auction. One of the mistakes the Europeans made in setting up a cap-and-trade system was to give too many of those permits away.”

Congress is now in the process of sending Obama a bill that makes exactly this mistake.

How much does it matter? For the purpose of efficiently allocating the carbon rights, it doesn’t. Even if these rights are handed out on political rather than economic grounds, the “trade” part of “cap and trade” will take care of the rest. Those companies with the most need to emit carbon will buy carbon allowances on newly formed exchanges. Those without such pressing needs will sell whatever allowances they are given and enjoy the profits that resulted from Congress’s largess.

The problem arises in how the climate policy interacts with the overall tax system. As the president pointed out, a cap-and-trade system is like a carbon tax. The price of carbon allowances will eventually be passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices for carbon-intensive products. But if most of those allowances are handed out rather than auctioned, the government won’t have the resources to cut other taxes and offset that price increase. The result is an increase in the effective tax rates facing most Americans, leading to lower real take-home wages, reduced work incentives and depressed economic activity.

The hard question is whether, on net, such a policy is good or bad. Here you can find policy wonks on both sides. To those who view climate change as an impending catastrophe and the distorting effects of the tax system as a mere annoyance, an imperfect bill is better than none at all. To those not fully convinced of the enormity of global warming but deeply worried about the adverse effects of high current and prospective tax rates, the bill is a step in the wrong direction.

What everyone should agree on is that the legislation making its way through Congress is a missed opportunity. Obama knows what a good climate bill would look like. But despite his immense popularity and personal charisma, he appears unable to persuade Congress to go along.

As for me, I hope the president refuses to sign a bill that fails to auction most of the allowances. Some might say a veto would make the best the enemy of the good. But sometimes good is not good enough.

N. Gregory Mankiw is a professor of economics at Harvard University. He was an adviser to former US president George W. Bush.

In the past month, two important developments are poised to equip Taiwan with expanded capabilities to play foreign policy offense in an age where Taiwan’s diplomatic space is seriously constricted by a hegemonic Beijing. Taiwan Foreign Minister Lin Chia-lung (林佳龍) led a delegation of Taiwan and US companies to the Philippines to promote trilateral economic cooperation between the three countries. Additionally, in the past two weeks, Taiwan has placed chip export controls on South Africa in an escalating standoff over the placing of its diplomatic mission in Pretoria, causing the South Africans to pause and ask for consultations to resolve

An altercation involving a 73-year-old woman and a younger person broke out on a Taipei MRT train last week, with videos of the incident going viral online, sparking wide discussions about the controversial priority seats and social norms. In the video, the elderly woman, surnamed Tseng (曾), approached a passenger in a priority seat and demanded that she get up, and after she refused, she swung her bag, hitting her on the knees and calves several times. In return, the commuter asked a nearby passenger to hold her bag, stood up and kicked Tseng, causing her to fall backward and

In December 1937, Japanese troops captured Nanjing and unleashed one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century. Over six weeks, hundreds of thousands were slaughtered and women were raped on a scale that still defies comprehension. Across Asia, the Japanese occupation left deep scars. Singapore, Malaya, the Philippines and much of China endured terror, forced labor and massacres. My own grandfather was tortured by the Japanese in Singapore. His wife, traumatized beyond recovery, lived the rest of her life in silence and breakdown. These stories are real, not abstract history. Here is the irony: Mao Zedong (毛澤東) himself once told visiting

When I reminded my 83-year-old mother on Wednesday that it was the 76th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, she replied: “Yes, it was the day when my family was broken.” That answer captures the paradox of modern China. To most Chinese in mainland China, Oct. 1 is a day of pride — a celebration of national strength, prosperity and global stature. However, on a deeper level, it is also a reminder to many of the families shattered, the freedoms extinguished and the lives sacrificed on the road here. Seventy-six years ago, Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東)