For months, European car buyers have been junking clunkers for cash, boosting automakers sales — but making experts fear that once the government handouts stop, the struggling car industry will return to a slump that no pile of cash can conquer.

The various programs have surged in popularity since France introduced the idea in December.

Germany, Italy, Britain, Romania, Austria, the Netherlands, Spain and Serbia have introduced their own versions aimed at shoring up local automakers, from Germany’s Daimler AG to Romania’s Dacia.

While critics contend the billions of dollars in handouts only benefit automakers at the expense of other industries and have just delayed a slump in car sales, proponents say it has kept large companies operating and helped reduce layoffs and temporary shutdowns.

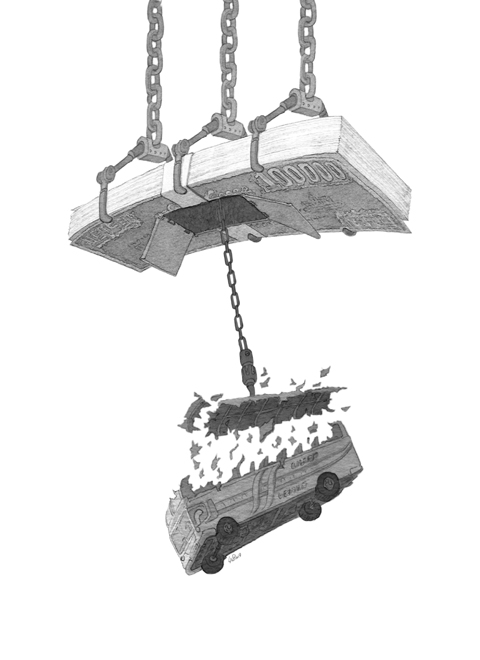

But only for a time, some fear. The question is, what happens when the money runs out — will the industry ease off the ramp or drive off a cliff?

“It is a question of somewhat forestalling the inevitable,” Paul Newton, an auto analyst for IHS Global Insight, said on Friday. “The reality is that without it, the chances are you’ll see a lot of businesses going to the wall.”

Instead, he said that auto companies and dealership owners are using the programs, for now, to clear inventory and build up cash on hand before “what is very likely to be a very tough 2010.”

US officials consulted with Germany before implementing their own version of the auto rebate program, according to guidelines published by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the federal agency running the US cash-for-clunkers effort.

One dramatic difference? The US has idled the clunkers by requiring dealers to kill the engine by pouring sodium silicate into it in order to claim a refund for the clunker rebate. The substance, often referred to as liquid glass, permanently damages engine parts.

German officials noted this week that there has been firm evidence of clunkers there being routed abroad — to Africa and even eastern Europe — and being resold. The Association of Criminal Investigators, estimated that about 50,000 cars — polluting makes and models — have been sent outside of Germany. Clunkers in Germany aren’t required to have their engines disabled and thousands have not made it to the scrap yard.

The programs have drawn fierce criticism. Last month, Czech President Vaclav Klaus vetoed parts of a stimulus package, including a local version of the cash for clunkers.

His office said the measure favored “short-term interests of several strong players from the auto industry at the expense of other sectors and firms.”

In Germany, critics have likened the bailout to giving free drugs to addicts.

“The auto industry is waiting on the bonus like a drug addict waits for the next shot,” Steffen Kampeter, a senior lawmaker of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats, was quoted as telling the Financial Times Deutschland newspaper. “It should instead put forward concepts on how it plans to deal with the structural challenges for the industry.”

Sylvie Cariou, the director of a Citroen dealership just outside of Paris, said that as soon as France implemented its own program, the impact was noticeable.

“Right away, the effect that we saw was more traffic” in her dealership, she said. “For people who didn’t think they could afford a car, it motivated them to buy.”

Across Europe, the programs helped to limit the year-on-year sales decline in the second quarter to 5.6 percent, compared with a 17.4 percent drop in the first quarter.

European manufacturers group ACEA reported a 2.4 percent rise in European car sales in June, the first increase after 14 months of falling sales.

It said sales at Europe’s top seller, Volkswagen AG, rose 9.5 percent, while Italy’s Fiat saw a 11.7 percent gain as its cheaper small cars sold strongly. Peugeot Citroen SA sales increased 4.4 percent, Ford Motor Co rose 2.2 percent and Renault SA was up 3.4 percent.

Among the chief beneficiaries have been makers of small cars such as Peugeot and Fiat.

After France launched its program in December, Renault said that orders for its cars were boosted by 40 percent that month by the government-sponsored 1,000 euro (US$1,435) bonus for French consumers who trade in old cars for new, lower-emissions models.

Germany quickly followed suit, starting its plan in February after Europe’s biggest economy fell into a recession.

Owners of cars that are at least nine years old and registered in Germany for at least a year receive a 2,500 euro bonus if they buy a new car. The initial goal was to help the economy — which is expected to shrink by some 6 percent this year — by promoting big-ticket consumer purchases and newer, lower-emissions vehicles.

The government seeded 1.5 billion euros for the program, but it proved so popular that it was increased to 5 billion euros. To date, around 1.7 million applications have been received, tying up around 4.3 billion euros.

Other countries, including Italy, Spain and Britain, quickly followed suit, as did the US, which on Thursday earmarked another US$2 billion to its own program — bringing it to US$3 billion.

“There is not a single doubt that, if the incentives are removed from the European arena, they will have a substantial impact on demand,” Fiat SpA chief executive Sergio Marchionne said of the programs, which helped it reduce temporary layoffs and has sparked demand for its Fiat Panda model.

Some analysts also insist that the surge in sales is not merely pushing up demand, leaving automakers to face a precipice once the incentives are removed, but are instead creating sales because buyers trading in older polluting models would normally buy used, not new, cars.

How long they can last, though, is not certain. Germany — home to Volkswagen, BMW and Daimler — has made clear that when the money runs out, the program won’t be continued.

“After that, it’s over,” German Economy Minister Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg said.

Europe’s auto makers are pleading for governments to withdraw the support gradually, fearing that until the economy is back on track, a dramatic end to the plans could result in a disorderly collapse in demand and chaos in the industry.

Renault chief operating officer Patrick Pelata said such schemes can’t last forever, but the crisis “is still here.”

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

For nearly eight decades, Taiwan has provided a home for, and shielded and nurtured, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). After losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the KMT fled to Taiwan, bringing with it hundreds of thousands of soldiers, along with people who would go on to become public servants and educators. The party settled and prospered in Taiwan, and it developed and governed the nation. Taiwan gave the party a second chance. It was Taiwanese who rebuilt order from the ruins of war, through their own sweat and tears. It was Taiwanese who joined forces with democratic activists

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) held a news conference to celebrate his party’s success in surviving Saturday’s mass recall vote, shortly after the final results were confirmed. While the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would have much preferred a different result, it was not a defeat for the DPP in the same sense that it was a victory for the KMT: Only KMT legislators were facing recalls. That alone should have given Chu cause to reflect, acknowledge any fault, or perhaps even consider apologizing to his party and the nation. However, based on his speech, Chu showed