What international association brings together 18 countries straddling three continents thousands of kilometers apart, united solely by their sharing of a common body of water?

That is a quiz question likely to stump the most devoted aficionado of global politics. It’s the Indian Ocean Rim Countries’ Association for Regional Cooperation, blessed with the unwieldy acronym IOR-ARC, perhaps the most extraordinary international grouping you have ever heard of.

The association manages to unite Australia and Iran, Singapore and India, Madagascar and the United Arab Emirates, and a dozen other states large and small — unlikely partners brought together by the fact that the Indian Ocean washes their shores. I have just come back from attending the association’s ministerial meeting in Sanaa, Yemen. Despite being accustomed to my eyes glazing over at the alphabet soup of international organizations I have encountered during a three-decade-long UN career, I find myself excited by the potential of IOR-ARC.

Regional associations have been created on a variety of premises: geographical, as with the African Union; geopolitical, as with the Organization of American States; economic and commercial, as with ASEAN or Mercosur; and security-driven, as with NATO. There are multi-continental ones, too, like IBSA, which brings together India, Brazil and South Africa, or the better-known G8.

Even Goldman Sachs can claim to have invented an intergovernmental body, since the “BRIC” concept coined by that Wall Street firm was recently institutionalized by a meeting of the heads of government of Brazil, Russia, India and China in Yekaterinburg, Russia, last month. But it is fair to say there is nothing quite like IOR-ARC in the annals of global diplomacy.

For one thing, there is not another ocean on the planet that takes in Asia, Africa and Oceania — and could embrace Europe, too, since the French department of Reunion, in the Indian Ocean, gives France observer status in IOR-ARC, and the French foreign ministry is considering seeking full membership.

For another, every one of Samuel Huntington’s famously clashing civilizations finds a representative among its members, giving a common roof to the widest possible array of world views in their smallest imaginable combination (just 18 countries). When IOR-ARC meets, new windows are opened between countries separated by distance as well as politics.

Malaysians talk with Mauritians, Arabs with Australians, South Africans with Sri Lankans, and Iranians with Indonesians. The Indian Ocean serves as both a sea separating them and a bridge linking them together.

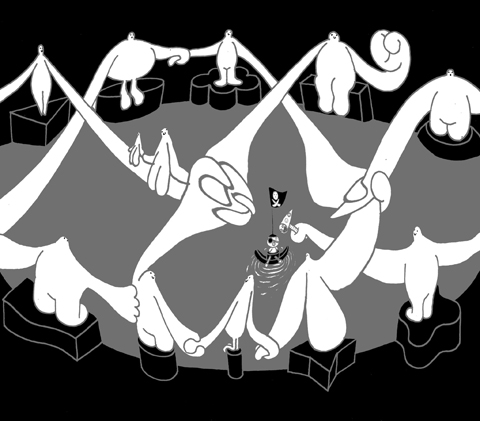

The potential of the organization is huge. There are opportunities to learn from one another, to share experiences and to pool resources on such issues as blue-water fishing, maritime transport and piracy in the Gulf of Aden and the waters off Somalia, as well as in the Strait of Malacca.

But IOR-ARC does not have to confine itself to the water: It’s the countries that are members, not just their coastlines. So everything from the development of tourism in the 18 countries to the transfer of science and technology is on the table. The poorer developing countries have new partners from which to receive educational scholarships for their young and training courses for their government officers. There is already talk of new projects in capacity building, agriculture and the promotion of cultural cooperation.

This is not to imply that IOR-ARC has yet fulfilled its potential in the decade that it has existed. As often happens with brilliant ideas, the creative spark consumes itself in the act of creation, and IOR-ARC has been treading water, not having done enough to get beyond the declaratory phase that marks most new initiatives. The organization itself is lean to the point of emaciation, with just a half-dozen staff — including the gardener — in its Mauritius secretariat. The formula of pursuing work in an Academic Group, a Business Forum and a Working Group on Trade and Investment has not yet brought either focus or drive to the parent body.

But such teething pains are inevitable in any new group, and the seeds of future cooperation have already been sown. Making a success of an association that unites large countries and small ones, island states and continental ones, Islamic republics, monarchies and liberal democracies, and every race known to mankind, represents both a challenge and an opportunity.

This diversity of interests and capabilities can easily impede substantive cooperation, but it can also make such cooperation far more rewarding. In this diversity, we in India see immense possibilities, and in Sanaa we pledged ourselves to energizing and reviving this semi-dormant organization. The brotherhood of man is a tired cliche, but the neighborhood of an ocean is a refreshing new idea. The world as a whole stands to benefit if 18 littoral states can find common ground in the churning waters of a mighty ocean.

Shashi Tharoor, minister of state for external affairs for India, is a former UN undersecretary-general and an award-winning novelist and commentator.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

Workers’ rights groups on July 17 called on the Ministry of Labor to protect migrant fishers, days after CNN reported what it described as a “pattern of abuse” in Taiwan’s distant-water fishing industry. The report detailed the harrowing account of Indonesian migrant fisher Silwanus Tangkotta, who crushed his fingers in a metal door last year while aboard a Taiwanese fishing vessel. The captain reportedly refused to return to port for medical treatment, as they “hadn’t caught enough fish to justify the trip.” Tangkotta lost two fingers, and was fired and denied compensation upon returning to land. Another former migrant fisher, Adrian Dogdodo