As night gave way to dawn, the dancing only intensified. The DJ built toward the furious climax, when columns of fire shot into the air and confetti rained down on the screaming crowd.

“Here, Ecstasy is everywhere,” said Mateus Loiecomo, 19, referring to the drug that helped fuel the long night of dancing for a number of the revelers.

He waved an arm at dozens of young people exiting with large sunglasses, their hair soaked with sweat.

“But everybody should be allowed to take whatever drug they want,” he said. “It’s their life, right?”

Argentina is adopting an increasingly liberal attitude toward recreational drug use, with the government of President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner moving to decriminalize the personal use of illicit substances and give the country one of the more tolerant drug-consumption policies in the world.

“I don’t like it when people condemn someone who has an addiction as if he were a criminal, as if he were a person who should be persecuted,” Kirchner said in August. “The ones that should be persecuted are the ones who sell the substances, who give it away, who traffic in it.”

That attitude is shared across Latin America, where governments or high courts in Ecuador, Colombia and Mexico have also recently moved to decriminalize small-scale possession for personal use.

Even so, the rising consumption of Ecstasy in Argentina has largely caught officials by surprise, helping ignite a heated debate in recent weeks over the government’s new drug policy.

Several provincial governors, as well as Kirchner’s own vice president, have spoken out against the proposal, which may go before Congress before the end of this month.

Also due soon is a decision from the Argentine Supreme Court on whether to uphold a lower court’s ruling invalidating a 20-year-old law imposing criminal penalties on drug users.

Meanwhile, a dispute has also erupted between the justice minister, who is promoting the idea of decriminalization, and the director of the government’s drug control and addiction prevention agency, who expresses skepticism, leading to much finger-pointing over who is to blame for the country’s drug problems.

Even the partygoers cannot agree. Sitting outside a club at 7am after a long night of dancing in this resort city on the Atlantic coast, Federico de la Rosa, 20, said that the law would be “way too liberal” if the policy was changed.

“Teenagers would not have any problems scoring drugs,” said de la Rosa, an architecture student. “To me, that’s not a good thing.”

Argentina already has the highest per-capita use of cocaine in the Americas after the US, a 2006 survey by the UN showed. But throughout Latin America, prison overcrowding is helping to soften policies on drug use, said Martin Jelsma, coordinator of the program on drugs at the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam, a research organization. So, too, is the notion that traditional approaches to limiting drug consumption and trafficking have not been working.

Last week, a commission led by three former Latin American presidents issued a report condemning the US-led “war on drugs” and saying that policies based on “the criminalization of consumption have not yielded the expected results.” The commission recommended that drug addicts be considered “patients of the healthcare system,” not “drug buyers in an illegal market.”

In Argentina, 70 percent of cases resulting in prison sentences in 2006 involved users arrested for having small amounts of drugs for personal use, said Monica Cunarro, an independent lawyer who leads the justice ministry committee studying the change in the drug law.

At the same time, Cunarro said, the anti-drug agency have been ineffective in slowing the drug trade, while dealers and big traffickers evaded jail because of corruption among the nation’s police forces.

Jose Ramon Granero, who leads the government’s drug control division, defended his agency’s actions, arguing that a proposal to crack down on chemical precursors used in drug production had been stalled in the justice ministry since 2005.

He also played down accusations against him relating to the discovery in December of about 8kg of cocaine in a van sent by the agency to a shop to be reupholstered. He said he thought the drugs had not been detected when the van was initially seized in a raid that found more than 20kg of cocaine in the vehicle.

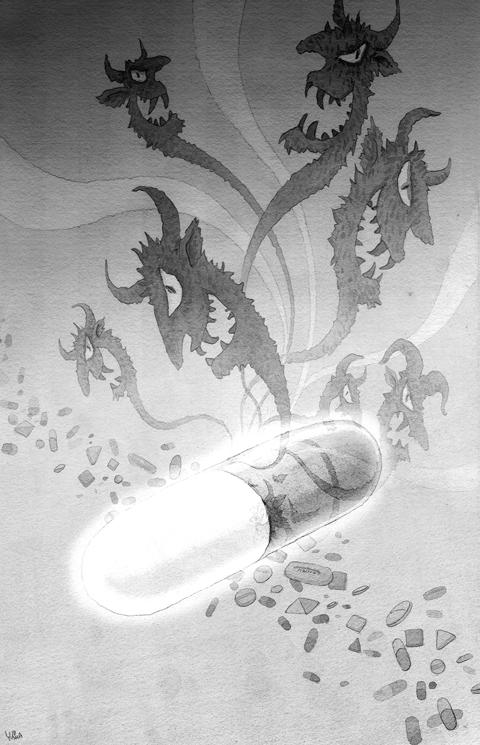

Recriminations aside, rising Ecstasy consumption in Argentina has taken a toll on users.

The government does not keep records on the number of deaths related to its use, but the drug appears to have been involved in a handful of fatalities in the past three years and is suspected in several others, Granero said.

The connection to the electronic music world is so strong here that anti-drug campaigners say some organizers of raves offer two kinds of admission: a regular entrance pass and a more expensive “plus” pass that includes an Ecstasy pill.

Granero said festival organizers had obstructed government efforts to monitor such events. In 2006, organizers of the annual Creamfields festival in Buenos Aires — the largest one-day electronic dance event in the world — rejected his request to allow two hospitals to set up emergency tents inside. Instead, the organizers set up their own health care station, he said, a decision the organizers did not deny.

“No one except them knows what happened inside,” he said.

In the past month, two important developments are poised to equip Taiwan with expanded capabilities to play foreign policy offense in an age where Taiwan’s diplomatic space is seriously constricted by a hegemonic Beijing. Taiwan Foreign Minister Lin Chia-lung (林佳龍) led a delegation of Taiwan and US companies to the Philippines to promote trilateral economic cooperation between the three countries. Additionally, in the past two weeks, Taiwan has placed chip export controls on South Africa in an escalating standoff over the placing of its diplomatic mission in Pretoria, causing the South Africans to pause and ask for consultations to resolve

An altercation involving a 73-year-old woman and a younger person broke out on a Taipei MRT train last week, with videos of the incident going viral online, sparking wide discussions about the controversial priority seats and social norms. In the video, the elderly woman, surnamed Tseng (曾), approached a passenger in a priority seat and demanded that she get up, and after she refused, she swung her bag, hitting her on the knees and calves several times. In return, the commuter asked a nearby passenger to hold her bag, stood up and kicked Tseng, causing her to fall backward and

In December 1937, Japanese troops captured Nanjing and unleashed one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century. Over six weeks, hundreds of thousands were slaughtered and women were raped on a scale that still defies comprehension. Across Asia, the Japanese occupation left deep scars. Singapore, Malaya, the Philippines and much of China endured terror, forced labor and massacres. My own grandfather was tortured by the Japanese in Singapore. His wife, traumatized beyond recovery, lived the rest of her life in silence and breakdown. These stories are real, not abstract history. Here is the irony: Mao Zedong (毛澤東) himself once told visiting

When I reminded my 83-year-old mother on Wednesday that it was the 76th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, she replied: “Yes, it was the day when my family was broken.” That answer captures the paradox of modern China. To most Chinese in mainland China, Oct. 1 is a day of pride — a celebration of national strength, prosperity and global stature. However, on a deeper level, it is also a reminder to many of the families shattered, the freedoms extinguished and the lives sacrificed on the road here. Seventy-six years ago, Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東)