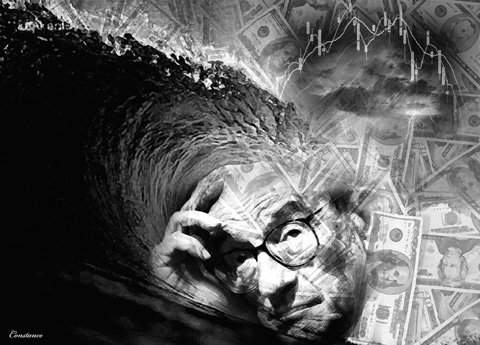

Economics, it seems, has very little to tell us about the current economic crisis. Indeed, no less a figure than former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan recently confessed that his entire “intellectual edifice” had been “demolished” by recent events.

Scratch around the rubble, however, and one can come up with useful fragments. One of them is called “asymmetric information.” This means that some people know more about some things than other people. Not a very startling insight, perhaps. But apply it to buyers and sellers. Suppose the seller of a product knows more about its quality than the buyer does, or vice versa. Interesting things happen — so interesting that the inventors of this idea received Nobel Prizes in economics.

In 1970, George Akerlof published a famous paper called “The Market for Lemons.” His main example was a used-car market. The buyer doesn’t know whether what is being offered is a good car or a “lemon.” His best guess is that it is a car of average quality, for which he will pay only the average price. Because the owner won’t be able to get a good price for a good car, he won’t place good cars on the market. So the average quality of used cars offered for sale will go down. The lemons squeeze out the oranges.

Another well-known example concerns insurance. This time it is the buyer who knows more than the seller, since the buyer knows his risk behavior, physical health and so on. The insurer faces “adverse selection” because he cannot distinguish between good and bad risks. He therefore sets an average premium too high for healthy contributors and too low for unhealthy ones. This will drive out the healthy contributors, saddling the insurer with a portfolio of bad risks — the quick road to bankruptcy.

There are various ways to “equalize” the information available — for example, warranties for used cars and medical certificates for insurance. But since these devices cost money, asymmetric information always leads to worse results than would otherwise occur.

All of this is relevant to financial markets because the “efficient market hypothesis” — the dominant paradigm in finance — assumes that everyone has perfect information and therefore that all prices express the real value of goods for sale.

But any finance professional will tell you that some know more than others, and that these people earn more, too. Information is king. But just as in used-car and insurance markets, asymmetric information in finance leads to trouble.

A typical “adverse selection” problem arises when banks can’t tell the difference between a good and bad investment — a situation analogous to the insurance market. The borrower knows the risk is high, but tells the lender it is low. The lender who can’t judge the risk goes for investments that promise higher yields. This particular model predicts that banks will over-invest in high-risk, high-yield projects, that is, asymmetric information lets toxic loans onto the credit market. Other models use principal/agent behavior to explain “momentum” (herd behavior) in financial markets.

Although designed before the current crisis, these models seem to fit current observations rather well: banks lending to entrepreneurs who could never repay, and asset prices changing even if there were no change in conditions.

But a moment’s thought will show why these models cannot explain today’s general crisis. They rely on someone getting the better of someone else: the better informed gain — at least in the short term — at the expense of the worse informed. In fact, they are in the nature of swindles. So these models cannot explain a situation in which everyone, or almost everyone, is losing — or, for that matter, winning — at the same time.

The theorists of asymmetric information occupy a deviant branch of mainstream economics. They agree with the mainstream that there is perfect information available somewhere out there, including perfect knowledge about how the different parts of the economy fit together. They differ only in believing that not everyone possesses it. In Akerlof’s example, the problem with selling a used car at an efficient price is not that no one knows how likely it is to break down, but rather that the seller knows perfectly well how likely it is to break down, and the buyer does not.

And yet the true problem is that in the real world no one is perfectly informed. Those who have better information try to deceive those who have worse, but they are deceiving themselves that they know more than they do. If only one person were perfectly informed, there could never be a crisis — someone would always make the right calls at the right time. But only God is perfectly informed, and He does not play the stock market.

“The outstanding fact,” John Maynard Keynes wrote in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, “is the extreme precariousness of the basis of knowledge on which our estimates of prospective yield have to be made.”

There is no perfect knowledge “out there” about the correct value of assets because there is no way we can tell what the future will be like.

Rather than dealing with asymmetric information, we are dealing with different degrees of no information. Herd behavior arises, Keynes thought, not from attempts to deceive but from the fact that in the face of the unknown we seek safety in numbers. Economics, in other words, must start from the premise of imperfect rather than perfect knowledge. It may then get nearer to explaining why we are where we are today.

Robert Skidelsky, a member of the British House of Lords, is professor emeritus of political economy at Warwick University, author of a prize-winning biography of the economist John Maynard Keynes and a board member of the Moscow School of Political Studies.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

Workers’ rights groups on July 17 called on the Ministry of Labor to protect migrant fishers, days after CNN reported what it described as a “pattern of abuse” in Taiwan’s distant-water fishing industry. The report detailed the harrowing account of Indonesian migrant fisher Silwanus Tangkotta, who crushed his fingers in a metal door last year while aboard a Taiwanese fishing vessel. The captain reportedly refused to return to port for medical treatment, as they “hadn’t caught enough fish to justify the trip.” Tangkotta lost two fingers, and was fired and denied compensation upon returning to land. Another former migrant fisher, Adrian Dogdodo