The first deep-sea mining machines — for extracting gold, silver and copper deposited near volcanic fissures on the ocean floor — are being built by a British engineering company. The pioneering designs, which will resemble giant, abrasive vacuum cleaners, are at the forefront of an emerging underwater mineral extraction industry that is sounding alarm bells among marine biologists and environmental scientists.

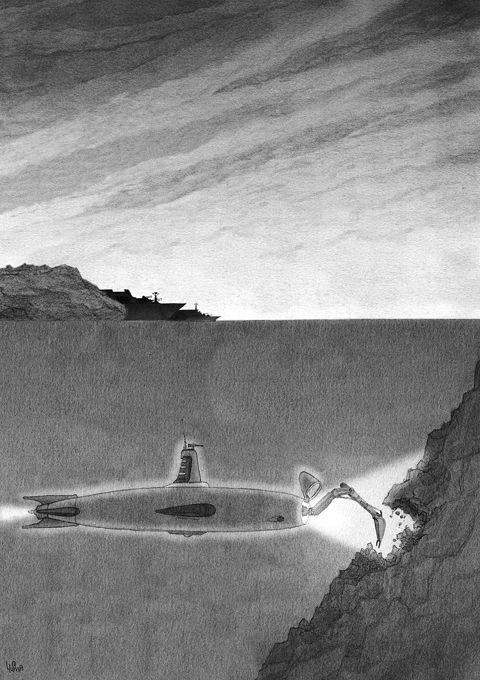

A £33 million (US$66 million) contract for two seafloor mining tools, capable of working at depths of more than 1,700m, was awarded last December to the Newcastle upon Tyne firm, Soil Machine Dynamics. If delivered according to schedule, the machines could begin excavation work by 2010 in the Pacific and inaugurate a new era in sub-sea exploration and mining.

The operation to recover these “poly-metallic” minerals, which are found in far higher concentrations than land-based ores, will generate a rich revenue source at a time when commodity prices are hitting record levels.

“We are leading the mining industry into the deep oceans,” said Scott Trebilcock, vice president of business development at Nautilus Minerals, the Canadian prospecting company that has ordered the machines.

“This is as big a change as it was for the oil and gas industry when it went offshore in the 1960s and 70s. Billions of dollars have been spent over decades developing [underwater] pumps, hydraulics and trench-digging machinery. We can use their technology for new targets: the poly-metallic deposits that contain gold, silver, zinc and copper,” he said.

Nautilus’s first project, the Solwara 1 field, is within Papua New Guinea’s territorial waters, but the firm, whose operational management is based in Brisbane, Australia, has also taken up license options on sites near Tonga, Fiji and New Zealand. Those locations have been chosen because of proximity to volcanic activity at the margins of the Earth’s tectonic plates.

“Deposits are formed from heated sea-water,” Trebilcock said. “As it filters deeper into cracks, it absorbs sulphur and becomes acidic. It can reach 300°C and dissolves minerals until it bubbles up and hits water on the ocean floor, which is at approximately 2°C.”

The metals precipitate out of solution and are deposited on the seabed. These so-called SMS — seafloor massive sulphides — resemble giant “elephant turds,” one oceanographer said.

Nautilus will work on underwater old vents that have cooled, some way back from the super-heated, active plate edges.

“Our material is 8 percent-10 percent copper,” Trebilcock said. “In land mines, the average is 0.5 percent. So for every tonne of copper produced, we move 40 times less material.”

Similar SMS deposits lie on the ocean floors around the world, particularly in the Arctic and along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Those areas, however, are at far greater depths and are subject to worse sea conditions.

Soil Machine Dynamics is designing and assembling a tool that has a rotating, cutting head — like the machines used to hew coal out of underground seams — surrounded by a giant suction pipe.

The company describes the equipment as “a novel design for recovering ore which is found in massive sulphide deposits in rugged terrain. It draws on technology developed in recent projects for trenching systems.”

The two seafloor mining systems will suck up 1.5 million tonnes of ore annually.

Trebilcock believes the operation will cause far less environmental damage than a similar-sized onshore mine.

“There’s no disturbance to the site around the mine. We’ll have no waste rock. Everything we take up will be smelted,” he said.

“We have carried out an environmental impact study, which will be published this year. We will have to show that we don’t have any long-term impact on any species or ecosystems. We have spoken to NGOs [non-governmental organizations] and the Papua New Guinea government about this,” he said.

“Oil and gas [companies] disturb a far larger area when they open up a new field. The dredging industry takes millions of tonnes off the ocean floor. We have significant [environmental] advantages over land-based companies,” he said.

However, some environmental groups are concerned that underwater mining will lead to despoilation of vast tracts of the seabed before they can be explored.

“These sites have limited physical integrity and great biodiversity,” Simon Cripps, director of WWF’s global marine program, recently told Chemistry World magazine.

“We would like to see a thorough, independent impact assessment before any mining work begins,” he said.

Catherine Coumans, a coordinator at Mining Watch Canada, has been to Papua New Guinea to examine the impact of mining.

“I have studied mines ... where the tailings [wastes] are flushed out to sea or simply dumped in rivers,” she said. “[Papua New Guinea] has, tragically, some of the worst forms of mining and disposal. Now it is going to have experimental undersea mining.”

“There are concerns about disturbance of the sea bottom. Very little is known about it. This is a new frontier that has yet to be explored with a fragile, marine ecosystem. There’s no significant independent work that has been done on the impact of mining. I would challenge the company to provide an independent scientific study,” she said.

Nautilus will not be the first underwater mining operation in the world.

De Beers has been stripping diamonds from the seabed off Namibia for several years, but at far shallower depths — generally around 150m.

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

For nearly eight decades, Taiwan has provided a home for, and shielded and nurtured, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). After losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the KMT fled to Taiwan, bringing with it hundreds of thousands of soldiers, along with people who would go on to become public servants and educators. The party settled and prospered in Taiwan, and it developed and governed the nation. Taiwan gave the party a second chance. It was Taiwanese who rebuilt order from the ruins of war, through their own sweat and tears. It was Taiwanese who joined forces with democratic activists

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) held a news conference to celebrate his party’s success in surviving Saturday’s mass recall vote, shortly after the final results were confirmed. While the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would have much preferred a different result, it was not a defeat for the DPP in the same sense that it was a victory for the KMT: Only KMT legislators were facing recalls. That alone should have given Chu cause to reflect, acknowledge any fault, or perhaps even consider apologizing to his party and the nation. However, based on his speech, Chu showed