Every year, World Water Week gathers experts and UN officials in their thousands, uttering vitriolic statements, holding meetings and forming alliances -- but ignoring the real problem that prevents a billion people getting decent water: Bad management.

This year, the main issue is (surprise, surprise!) climate change. But, whether or not climate change will increase droughts or increase rainfall, none of these meetings will lead to better water management because that management is generally accepted as a natural state monopoly: "Only governments can reach the scale necessary to provide universal access to services that are free or heavily subsidized for poor people and geared to the needs of all citizens," Oxfam says.

Water, like any resource, is scarce in many places. Normally, scarcity or demand drives people to devote their time, ingenuity and money to finding more efficient ways of using resources and increasing supplies. These entrepreneurs, whether they produce or sell wheat, shoes or water, need to be able to make a living out of their business -- but in most countries private water business is illegal.

To understand the problem with water, it is useful to look at another liquid resource: petroleum.

The management of water and of oil is heavily politicized -- oil supply is subject to cartels and political tensions, while water is one of the most heavily regulated and controlled goods on earth. And both are distributed unevenly across the globe: The Middle East is rich in oil but poor in water.

Still, to a large degree, oil production, transport and use is managed largely through the market process. As a result, its price enables all market participants -- from explorers to consumers -- to decide how much to use and whether to invest in the business.

Human ingenuity has been invested in discovering more oil and better ways of handling and using it because, when there is potential for reward, people invest their own resources (effort, skill, money and time).

Thanks to such investments, oil now accounts for 40 percent of the world's energy, supply has multiplied by more than 150 during the past century and the price has remained similar in real terms over that time. And this dangerous substance is transported safely to every corner of the world.

As with oil, water requires processing and transport. Water for households or industry generally requires treatment. It must also be transported from wells and reservoirs, whether by human, animal or mechanical labor or through pipes. And once water has been used, it needs to be properly disposed of or it can exacerbate the spread of diseases such as cholera and even contaminate clean water.

If water were oil, entrepreneurs would pounce upon myriad opportunities to find new or better ways to treat, distribute, use and recycle it. But, unlike oil, water is rarely subject to market processes.

Without the benefits of competition, water policy is determined by lobbying, corruption and inefficiency. This explains why in most poor countries, from Pakistan to Peru, farmers pay a subsidized price for water. This causes waste and shortages, usually to the detriment of the poor, who must spend their own scarce time and money in pursuit of other sources of water. For instance, 30 percent of India's urban population lacks access to municipal water. Around the world, slums rarely have any municipal supply.

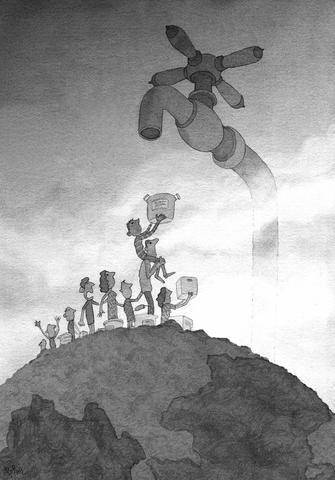

So, like with any other goods or services, the unconnected obtain water from entrepreneurs who use pushcarts, donkeys, water tankers or even private pipes: the World Bank estimates that half of urban residents in poor countries get their water from such private suppliers, especially in slums -- from South American aguateros to African jerrycan vendors.

The key to solving water scarcity in urban areas could lie with innovative entrepreneurs. Yet they are usually prevented from providing water more widely because their businesses are illegal or "informal."

Water is a more basic human need than oil so humans deserve the full benefits of the market process. This suggestion infuriates the many activists and politicians who believe that water is somehow special (unlike food, clothing and shelter) and must remain in government hands.

"Water privatization simply doesn't work" and governments should "invest instead in public solutions to the global water crisis," says the World Development Movement, which includes Oxfam and Christian Aid as partners.

So the poor must remain the victims of water policies created in their name but formed by corruption and cronyism.

Instead of being a political, emotive issue, the solution to water scarcity is to free it, so water can benefit from the economic forces of supply and demand and the startling power of innovation and enterprise.

Caroline Boin is a research fellow in the environment program at International Policy Network (IPN), an educational think-tank based in London. Kendra Okonski is editor of The Water Revolution and is environment program director of IPN.

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when