In any war, the primary focus is on dead, wounded and displaced people. The number of people killed as a result of Israel's offensive in Lebanon at the time of writing is reported to be roughly 800 Lebanese and 120 Israelis -- a typical ratio for Arab-Israeli conflicts. The UN estimates the number of displaced persons to be more than a million, about 800,000 of them Lebanese.

Damage to infrastructure and the environment will also continue to be felt once hostilities cease. Of course, infrastructure can be rebuilt much more quickly than the environment can be restored or recover on its own. In the case of Lebanon, however, the two are closely linked, as much of the environmental damage comes from destroyed infrastructure.

As in most modern wars, oil spills are one of the most visible -- and therefore most reported -- forms of environmental damage. Until the war started, Lebanon's beaches were among the cleanest in the Mediterranean. They are now to a large extent covered with oil. For a rare species of sea turtle this is bad news, as the eggs laid in the sand on those very beaches in the annual spawning season are due to hatch at precisely this time of the year. The total amount of oil released into the sea is now well over 100,000 tonnes.

Naturally, oil cisterns are not the only targets, and coastal locations are not the only regions hit. It is far too early to assess the damage done by releases of other, less visible, chemicals, but it is safe to assume that ground water will be contaminated for a long time. The drier the environment, the worse the problem.

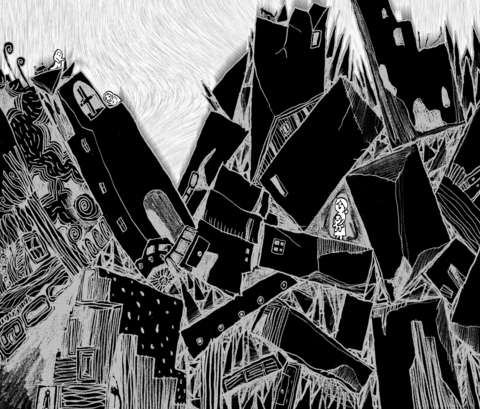

Moreover, bombs and grenades not only ignite buildings, but also grass, bushes and trees. The number of forest and brush fires that start is thus much higher than during a normal summer. Worse still, there is little capacity to fight them, as existing firefighting resources are used to try to save human lives. Consequently, bushes and forests burn, reducing the stands of cedar trees -- a symbol of Lebanon as much as the bald eagle is of the US, and just as close to extinction. A unique ecosystem is being lost.

There have also been reports, more often on the Internet than in the press, about despairing Lebanese doctors, who, not recognizing the wounds patients have sustained after Israeli air strikes, have described what they see and asked colleagues around the world for help.

One such type of wound reportedly resembles second-degree burns over large parts of bodies, but with the hairs intact not a typical reaction to fire and heat. There have been suggestions that agents containing some acid or alkali were possibly stored in buildings destroyed in the bombing.

According to this theory, such agents were dispersed after a missile or bomb hit, rather than being delivered with incoming warheads. The last word probably has not been heard. One has only to recall Gulf War Syndrome, which emerged after the 1991 conflict, and the controversy surrounding the issue of what, if anything, affected US soldiers, to understand how difficult it can be to answer such questions until well after the fact.

The worst environmental effect on health is probably the one most directly associated with the destruction of infrastructure: the release of asbestos. As in many parts of the world with hot climates, apartment and office buildings in Lebanon use asbestos for heat insulation. This has been standard practice for decades, and most buildings that have been erected or restored since Israel's last bombings in 1982 have plenty of it.

When pulverized by bombs and missiles, asbestos fibers are freed and can be inhaled with the rest of the dust. The protective suits that specially-trained people are legally required to wear in the EU or the US when demolishing, rebuilding or repairing any building containing asbestos underscore the risk of pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer for Lebanese who inhale dust from bombed-out houses and offices. Indeed, US companies have been forced to pay tens of billions of dollars to former employees who worked with asbestos.

Lebanon cannot afford to pay anything close to such a sum. But this is just one of many environmental debts that will somehow have to be paid in long after the fighting has stopped by the victims, if by nobody else.

Arne Jernelov is professor of environmental biochemistry, former director of the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis in Vienna and a UN expert on environmental catastrophes.

copyright: project syndicate

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

The stocks of rare earth companies soared on Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10 percent stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp, exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned US growth and innovation since its founding. Prior to Intel’s Jan. 22 call with analysts

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

International debate on Taiwan is obsessed with “invasion countdowns,” framing the cross-strait crisis as a matter of military timetables and political opportunity. However, the seismic political tremors surrounding Central Military Commission (CMC) vice chairman Zhang Youxia (張又俠) suggested that Washington and Taipei are watching the wrong clock. Beijing is constrained not by a lack of capability, but by an acute fear of regime-threatening military failure. The reported sidelining of Zhang — a combat veteran in a largely unbloodied force and long-time loyalist of Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) — followed a year of purges within the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA)