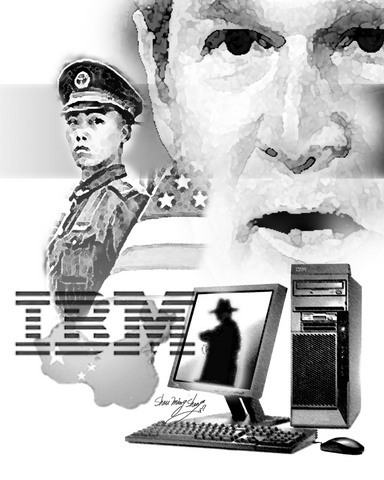

Long story short, an influential member of Congress played the China card, and the State Department folded.

It was a drama that reached its conclusion late last week, when the State Department, responding to fears that its security might be breached by a secretly placed device or hidden software, agreed to keep personal computers made by Lenovo of China off its networks that handle classified government messages and documents.

The damage to Lenovo is more to its reputation than to its pocketbook. The State Department will use the 16,000 desktop computers it purchased from Lenovo, just not on the computer networks that carry sensitive government intelligence.

Yet the episode does point to how much relations between the US and China have become a tangled web of political, trade and security issues. Mutual economic dependence and mutual distrust, it seems, go hand in hand.

To the Lenovo side, the outcome was a matter of anti-China politics overriding economic logic.

Last year, the Chinese company completed the purchase of the personal computer business of IBM, after the administration of President George W. Bush concluded a national security review. Given the nod, Lenovo figured it was free to do business in the US just like any other personal computer company.

But the State Department decision suggests that it is not that simple. "Unfortunately, we're in a situation where certain people in Congress and elsewhere want to make a political issue of this," said Jeffrey Carlisle, vice president of government relations for Lenovo. "They are trying to create as uncomfortable an atmosphere as possible for us in doing business with the federal government."

Carlisle characterizes the worry that the Chinese government might secretly slip spying hardware or software on Lenovo computers shipped to the State Department as "a fantasy." The desktop machines, he said, will be made in Monterrey, Mexico, and Raleigh, N.C., at plants purchased from IBM.

"It's the same places, using the same processes as IBM had," Carlisle said. "Nothing's changed."

Representative Frank R. Wolf, however, said that the change of ownership changes a lot. In a letter to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice earlier this month, he wrote that because of the Chinese government's "coordinated espionage program" intended to steal US secrets, the Lenovo computers "should not be used in the classified network."

Wolf is the chairman of the House subcommittee that oversees the budget appropriations for the State Department, Commerce Department and Justice Department.

bipartisan decision

In an interview on Monday, Wolf said the security concerns about the State Department's use of Lenovo computers had been brought to his attention by two members of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a bipartisan group appointed by Congress.

"They deserve the credit for this," Wolf said.

Larry Wortzel, a member of the review commission and former military attache to the US embassy in Beijing, said he and another commission member, Michael Wessel, began looking into the sale in March. What most concerned them, he said, was that 900 of the Lenovo computers were intended for use on the State Department's classified networks.

Lenovo is partly owned by the Chinese government, which holds 27 percent. "This is a company owned and beholden to agencies of the People's Republic of China," Wortzel said. "Our assumption is that if the Chinese intelligence agencies could take action, they would take action."

After meetings with US government securities agencies, including classified briefings, Wortzel and Wessel concluded that it would be possible for the Chinese government to put clandestine hardware or software on personal computers that might be able to tap into US intelligence.

"This is not off the wall as to whether there are potential security concerns here," Wessel said.

Both Wortzel and Wessel insisted that theirs is not an anti-China stance or even anti-Lenovo.

"I'm sure they are very good computers," Wortzel said. "I would use them in my home. But I would not use one on a classified network at the State Department."

The State Department said last week that it would not use the Lenovo computers on its classified networks. In a letter to Wolf, Richard Griffin, assistant secretary of state for diplomatic security, said that the department had "consulted with US government security experts and is recommending that the computers purchased last fall be utilized on unclassified systems only."

routine testing

The letter added that the State Department was "initiating changes in its procurement processes in light of the changing ownership" of computer equipment suppliers.

A spokesman said that "to allay any possible fears and any possible concerns, this is where we came out."

Certainly, there are fears aplenty these days in any matter related to China. Carlisle of Lenovo insists any security fears about its computers are unfounded. The company's computers and the software loaded on them are routinely tested inside the company and, on the State Department sale, by third-party US contractors.

"If anything were detected, it would be a death warrant for the company," Carlisle said. "No one would ever buy another Lenovo PC. It would make no sense to do it."

Lenovo, industry analysts say, may well have the stronger argument, but it may still suffer.

"Basically, this is much ado about nothing," said Roger Kay, president of Endpoint Technologies Associates. "Unfortunately, perceptions count. And the damage has already been done."

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just

On today’s page, Masahiro Matsumura, a professor of international politics and national security at St Andrew’s University in Osaka, questions the viability and advisability of the government’s proposed “T-Dome” missile defense system. Matsumura writes that Taiwan’s military budget would be better allocated elsewhere, and cautions against the temptation to allow politics to trump strategic sense. What he does not do is question whether Taiwan needs to increase its defense capabilities. “Given the accelerating pace of Beijing’s military buildup and political coercion ... [Taiwan] cannot afford inaction,” he writes. A rational, robust debate over the specifics, not the scale or the necessity,