A tear rolls down Sabaheta Fejzic's cheek as she twists open the blue tin of hand cream and gazes at the fingertip tracks left by her son. The 17-year-old and his father have never been seen since they were taken away to the factory where Europe's worst massacre since World War II was being perpetrated.

Nearly 8,000 people died in the five-day bloodbath of Srebrenica that was set in motion 10 years ago on Monday with the Bosnian-Serb capture of the town from UN peacekeepers. Over the next two days, troops rounded up the town's males, shot all who couldn't flee and scattered their remains in dozens of mass graves that are still turning up today.

Srebrenica was supposed to be a UN "safe haven" but its 600 Dutch peacekeepers, outmanned and outgunned, could only watch as soldiers supervised by Bosnian-Serb General Ratko Mladic separated men from women and children at a factory in the suburb of Potocari.

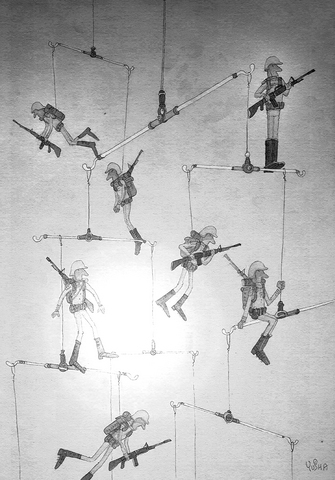

ILLUSTRATION: YUSHA

Ten years later, Srebrenica remains an emblem of a three-and-a-half-year war that left 260,000 dead and 20,000 missing. Even now some 800,000 remain uprooted, often -- as in the case of Srebrenica's Muslims -- afraid to go back to towns now run by their former enemies.

Rijad, Fejzic's only child, was taken from his mother on the morning of July 12. As the Serbs led him away, she grabbed his belt pack to hold him back. It broke off in her hands.

Opening it later, she found music cassettes of Dire Straits and Bosnian rockers, and the half-used Nivea tin.

"When you lift the lid you can see the traces of his fingertips in the cream," she says, searching for a tissue to catch her tears.

Bosnia now is united, on paper, as a Serb republic and a Muslim-Croat federation. But it still needs international supervision enforced by armed foreign peacekeepers to keep its ethnic groups working together in a central government.

Already inefficient before the war, its post-communist economy remains dependent on outside help.

The strong sense of accounts unsettled is highlighted by NATO forces' failure to capture Mladic, as well as the wartime Bosnian Serb leader, Radovan Karadzic, so that they can be tried for the Srebrenica massacre and other war crimes.

The US Congress recently passed a resolution deeming the Srebrenica killings to be genocide and demanding the perpetrators be punished.

But a text with the same message was voted down in Bosnia's federal parliament by Bosnian Serb lawmakers.

Still, after nearly a decade of denial, Serbs are starting to come to grips with their wartime conduct.

The evidence has become impossible to ignore, now that ordinary Serbs have seen TV footage of Srebrenica's victims being rounded up and shot.

Screened last month, the video has poked huge holes in the Serb nationalist spin on the Bosnian and other Balkan wars -- that Serbs were the victims and other ethnic groups the perpetrators.

The president of now defunct Yugoslavia, Slobodan Milosevic, was ousted by street protesters in 2001 and is on trial for war crimes in The Hague, Netherlands, and Monday's memorial in Srebrenica will for the first time be attended by a Serbian president, the pro-Western Boris Tadic. Organizers expect 50,000 people to show up.

In Belgrade, capital of neighboring Serbia, billboards have been put up by a human-rights group as a reminder of the Srebrenica anniversary.

They show a forensic examiner holding a human arm, a child's smashed doll, coffins awaiting burial.

Too subtle, says Dragana Marinkovic, 60, a passerby.

"You need to shock Serbia to make it face the past," he says.

Muslims like Fejzic need no reminders.

A tiny woman with dark brown hair and a permanently sad face, she remembers losing sight of Saban, her husband, in the melee of Serb soldiers, crying children and wailing women who had gathered in the UN compound. She tried to hold on to her son with both arms when the Serbs started separating the men from the women.

She fell on her knees and begged the soldiers to take her instead. Then she pleaded with them to kill her.

She remembers Rijad's thin shoulders heaving with sobs as he watched his mother crawling after him on all fours, clutching his fanny pack.

The remains of her son and husband have never been identified.

Since the previous anniversary, another 600 victims of the massacre, aged 14 to 75 and found in 60 mass graves, have been identified and will be buried on Monday at the cemetery of Srebrenica Muslims killed by Serbs.

Of the 2,079 sets of remains that have been identified by name after exhaustive investigations including DNA matching, the cemetery holds 1,327.

From missing-persons reports filed by close relatives, authorities estimate 7,800 people were massacred in Srebrenica.

Many may be among the 5,000 corpses stored in Bosnia pending identification. Or they may have belonged to families slaughtered in their entirety, leaving no one alive to report them dead.

Ahead of the ceremony, at the Potocari Memorial Center, work crews were busy repairing the main road into Srebrenica and digging graves.

"It's the only time I get some work for a few days," said Mirsad Karahasanovic, a 24-year old Muslim and temporary gravedigger.

Before the post-communist rivalries that led to the breakup of Yugoslavia, Bosnia was a place of ethnic coexistence and Srebrenica and the surrounding countryside were home to about 36,000 people, of whom 27,500 were Bosnian Muslim, the rest Serb and Croat.

Today, Srebrenica, whose name roughly means silver town, doesn't really come alive except for massacre anniversaries, when it fills with dignitaries, TV crews and massacre survivors.

Some 10,000 people are left, most of them Serbs. They are mostly shunned by the 1,000 Muslims who have returned to their old homes.

Not so the two 76-year-olds bantering and sipping coffee at a restaurant called Omer's, by a street sign from better days pointing to the Square of Brotherhood and Unity, surrounded by collapsed roofs and bullet-scarred walls. Bosko Obric is a Serb, his friend Edhem Delic a Muslim.

They talk about the supposed benefits of Srebrenica's waters -- enough to make an ugly person look good.

"It didn't work for you!" Delic says.

"Nor for you!" Obric retorts.

They erupt in hoots of laughter.

Fejzic, Rijad's mother, comes here for anniversaries, but otherwise avoids the town and her former Serb neighbors, who she says must share blame for the massacre because they were there, and in uniform.

"I will not return to Srebrenica while the perpetrators are still freely walking the streets and until I see Karadzic and Mladic in The Hague," she says.

"Only old people return here," says Obric, the Serb in the cafe. "Like elephants who come to die."

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other