The lead story in a recent issue of the Daily Graphic, Ghana's most influential newspaper, was designed to shock: "Four Gay Men Jailed." Homosexual acts are crimes in Ghana -- and across much of sub-Saharan Africa.

Uganda's leader, Yoweri Museveni, is vehemently opposed to homosexuality. So is Zimbabwe's embattled President Robert Mugabe. Namibia's President Sam Nujoma complains that the West wants to impose its decadent sexual values on Africa through the guise of gay tolerance.

Indeed, the global movement to fight discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS -- which first surfaced as a "gay disease" in the US -- has elicited little sympathy for homosexuals in sub-Saharan Africa. Only in South Africa have gays and lesbians won significant legal protections.

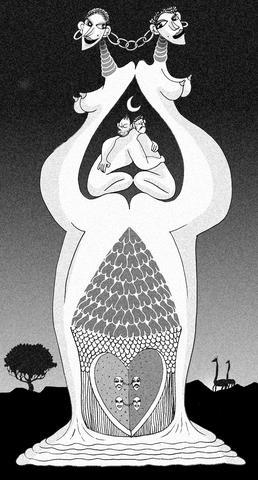

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

The arrests in Ghana, while typical of African bigotry towards gays, were all the more shocking because gays and lesbians actually thrive in Ghana's capital, Accra. A country of 20 million people, Ghana is unusually tolerant. Whites, Asians and Middle Easterners mix well. Ghana has never had a civil war -- a badge of honor in conflict-prone sub-Saharan Africa -- and three years ago staged a peaceful transfer of power from one elected government to another.

Although homosexuality remains taboo, gays seem safe. Physical attacks against them are rare. In Accra, a trendy street club named Strawberries is well known as a hangout for gays, and there are a few prominent, if still discreet, clubs where homosexual men and women gather. One gay man has his own television show, even though his sexual preferences are no secret.

Precisely because gays seem so accepted, the arrests sent a disturbing message. The paper that reported the story is owned by the government and sells more copies than all other newspapers combined. In the day following its original report, the Daily Graphic went further in showing its revulsion over gay activities by publishing a lead editorial that blamed Europeans and Americans for "all the reported cases of homosexuality" in Ghana.

The paper alleged that the men had been enticed into such practices by a Norwegian, who gave them money and gifts in exchange for photos of them engaged in homosexual acts. The Norwegian posted the photos on the Web and supposedly mailed printouts to his Ghanaian friends.

I am neither gay, nor Ghanaian, but I have spent considerable time in Ghana and I reject the argument -- heard in other parts of Africa as well -- that Western notions of sexuality have perverted Africans. In my experiences, Africans simply have a moral blind spot on the subject of homosexuality.

Journalists seem especially ignorant. Last year I worked in Ghana as country director of Journalists for Human Rights, a Canadian group that helps African journalists give voice to the voiceless in their society while raising awareness of human rights abuses. The editor of the Daily Graphic supported my organization, and I held training sessions for his newspaper's reporters and editors. The sessions resulted in stories that highlighted mistreatment of women and children and the failures of government agencies to deliver promised services. But when I complained about bias against gays, the editor responded that gays don't deserve any sort of protection.

Although this example may suggest that Africans are united against homosexuality, they are not; gay advocates are simply terrified of speaking out, frightened that their support will be interpreted as an admission that they are gay.

Two years ago, the silence was broken briefly by Ken Attafuah, who directs Ghana's truth and reconciliation commission, charged with investigating rights violations during two decades of dictatorships.

"It should not be left to gays alone to fight for gay rights, because we are talking about fundamental violations of justice," Attafuah said. "You do not have to be a child to defend the rights of children."

That point is lost in Ghana. After the gay arrests, I spoke at the University of Ghana about media coverage of homosexuals. While no one objected to the coverage by the Daily Graphic, no one denounced homosexuality either. Instead I received a short dissertation from one of the female students on how older married women often proposition her in nightclubs. Two other females said the same thing happens to them and asserted that lesbianism is widely practiced in Accra, if publicly unacknowledged.

Lesbianism is, of course, a less threatening practice to the men who run Ghana. No African man is supposed to be gay, and physical contact between men is presumed to be innocent.

Yet contradictions abound. Once, at a traditional ceremony, in which an infant child receives his tribal name, I watched the proud father and a half dozen male friends dance together before a crowd of well-wishers. The movements of these men were sexually suggestive, and at times they touched, even held hands. As I watched, a European next to me explained that such dancing is accepted, so long as the contact between the men is left undefined.

In Ghana and in much of Africa, a culture of silence exists around same-sex love -- a culture that many Westerners, raised on a belief in rights and openness -- find unacceptable. Yet the notion of "coming out" may not be a solution for every African homosexual. Notions of what is right and wrong often collapse under the irreconcilable tensions between tradition and modernity, the individual and the community.

In sub-Saharan Africa, I am reminded of the saying that silence is golden. Under the cover of silence, gays refrain from provoking the conflicts that a more vocal advocacy of homosexuality would bring. But the recent arrests in Ghana expose this strategy's true price.

Pascal Zachary is the author of The Diversity Advantage: Multicultural Identity in the New World Economy and a member of the board of the Toronto-based Journalists for Human Rights. Copyright: Project Syndicate

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in