The consecration and recognition of its first gay bishop threatens to split the Anglican communion down the middle. There has not been such ferment in the Church of England since the decision to ordain women to the priesthood. There is similar uproar in the US, where an openly gay priest has been elected Episcopalian bishop of New Hampshire, even though many American Christians regard a rejection of homosexuality as the benchmark orthodoxy.

Issues of sexuality and gender have long been the Achilles' heel of Western Christianity. Indeed, in the earliest days of the church, Christians had a jaundiced view of heterosexual marriage, and saw celibacy as the prime Christian vocation. Jesus had urged his followers to leave their wives and children (Luke 14:25-26). St Paul, the earliest Christian writer, believed that because Jesus was about to return and inaugurate the Kingdom of God, where there would be no marriage or giving in marriage, it was simply not worth saddling yourself with a wife or husband. This, Paul was careful to emphasize, was simply his own opinion, not a divine ruling. It was perfectly acceptable for Christians to marry if they wished, but in view of the imminent second coming, Paul personally recommended celibacy.

The fathers of the church often used these New Testament remarks to revile marriage, with the same intensity as those Christians who condemn homosexual partnerships today. The fathers accepted -- albeit grudgingly -- that marriage was part of God's plan. St Augustine taught that originally in the Garden of Eden, married sex had been rational and good. But after the fall, sexuality became a sign of humanity's chronic sinfulness, a raging and ungovernable force, a mindless, bestial enjoyment of the creature that held us back from the contemplation of God. Augustine's doctrine of original sin fused sexuality and sin indissolubly in the imagination of the Christian West.

For centuries this tainted the institution of matrimony. Augustine saw his conversion to Christianity as a vocation of celibacy.

"We ought not to condemn wedlock because of the evil of lust," he explained, "but nor must we praise lust because of the good of wedlock."

His teacher, St Ambrose of Milan, believed that "virginity is the one thing that keeps us from the beasts." The north African theologian Tertullian equated marriage with fornication.

"It is not disparaging wedlock to prefer virginity," wrote St Jerome. "No one can compare two things if one is good and the other evil."

When one of his women disciples contemplated a second marriage, Jerome turned on her in disgust: "The dog has turned to his own vomit again and the sow that was washed to her wallowing in the mire."

In England during the Middle Ages, couples were married in the church porch and not in the sanctuary -- a practice that eloquently revealed the liminal status of matrimony in the Christian worldview: Chaucer's Wife of Bath married five husbands "at the church door."

Even Luther, who left his monastery to marry, inherited Augustine's bleak view of sex.

"No matter what praise is given to marriage," he wrote, "I will not concede that it is no sin." Matrimony was a "hospital for sick people."

It merely covered the shameful act with a veneer of respectability, so that "God winks at it."

Calvin was the first Western theologian to praise marriage unreservedly, and thereafter Christians began to speak of "holy matrimony." The present enthusiasm for "family values" is, therefore, relatively recent.

In the Roman Catholic church, however, priests are still required to be celibate, and whatever the official teaching about the sanctity of marriage, the ban on artificial contraception implies that sex is only legitimate when there is a possibility of procreation. For most of its history, Christianity has had a more negative view of heterosexual love than almost any other major faith.

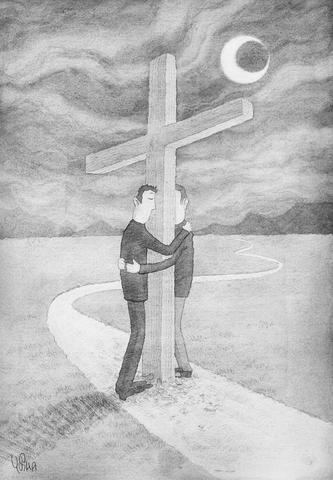

The current attempt to recognize homosexual partnerships is thus the latest development in a long struggle to bring sexuality into the ambit of the sacred. In principle, Christianity should have a special reverence for the physical, because it teaches that in some sense God took a human body and used it to redeem the world. But the evangelicals who oppose gay priests would argue that because the Bible condemns the sin of Sodom, the recognition of homosexuality is a step too far.

But in fact everybody reads the Bible selectively. If people followed every single biblical ruling to the letter, the world would be full of Christians who love their enemies and refuse to judge other people, which is plainly not the case.

Christians would also be obliged to eat kosher meat (Acts 15:20) and stone their disobedient sons to death (Deuteronomy 21:18-21). The world has changed and practices that were acceptable 2,000 years ago have become abhorrent.

We also have a more complex understanding of sexuality than the biblical writers.

Yet the Bible has to be read with care. The story of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19 condemns homosexual rape and the violation of the sacred rules of hospitality rather than homosexuality per se. It has nothing to say about the open, stable gay relationships that are essentially a feature of modern Western society, and did not exist in their current form in the biblical world.

Again, the rules against sodomy in Leviticus 18 and 20 are not legislating for ordinary human affairs. Throughout, the authors of Leviticus are chiefly concerned with temple ritual.

The practices forbidden in these chapters featured prominently in the idolatrous religions of the near east, which, as we know from the Bible, the people of Israel found extremely alluring: ritual bestiality (as practised in Egypt), child sacrifice, and the cultic use of menstrual blood in sorcery.

The verses against sodomy (Leviticus 18:22; 20:13) forbid temple prostitution: in the late 7th century BC, there had been a house of sacred male prostitutes in God's temple in Jerusalem (2 Kings 23:7) It is this kind of worship, which defiles the land, that concerns Leviticus.

In the same spirit, St. Paul's condemnation of the "unnatural practices" of the Graeco-Roman world springs from a visceral disgust with idolatry, the root cause of all the disorders in Paul's long list (Romans 1:20-31). The Bible is not a holy encyclopedia, giving clear and unequivocal information; nor is it a legal code that can be applied indiscriminately to our very different society.

Lifting isolated texts out of their literary and cultural context can only distort its message. Instead, we should look at the underlying principles of biblical religion, and apply these creatively to our own situation.

Modern readers frequently misunderstand Leviticus. Throughout the Pentateuch, the priestly writers insist on God's compassionate care for his creatures: all are pronounced good, exactly as he made them.

Even those animals declared "unclean" in the cult must be left in peace and their integrity respected. In the New Testament, Jesus goes out of his way to consort with those whose sexual lives were condemned by the self-righteous establishment. According to Jesus, nobody has the right to cast the first stone in these matters.

For centuries Christians failed to live up to this inclusive mandate, and found it difficult to accept their sexuality.

Eventually, however, they learned to overcome their prejudice in favor of celibacy, and realized that heterosexual marriage could bring them to God. They should now be ready for the next step.

Karen Armstrong is the author of A History of God.

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

More than a week after Hondurans voted, the country still does not know who will be its next president. The Honduran National Electoral Council has not declared a winner, and the transmission of results has experienced repeated malfunctions that interrupted updates for almost 24 hours at times. The delay has become the second-longest post-electoral silence since the election of former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez of the National Party in 2017, which was tainted by accusations of fraud. Once again, this has raised concerns among observers, civil society groups and the international community. The preliminary results remain close, but both

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

The Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation has demanded an apology from China Central Television (CCTV), accusing the Chinese state broadcaster of using “deceptive editing” and distorting the intent of a recent documentary on “comfort women.” According to the foundation, the Ama Museum in Taipei granted CCTV limited permission to film on the condition that the footage be used solely for public education. Yet when the documentary aired, the museum was reportedly presented alongside commentary condemning Taiwan’s alleged “warmongering” and criticizing the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government’s stance toward Japan. Instead of focusing on women’s rights or historical memory, the program appeared crafted