When Human Rights Watch declared last January that the Iraq War did not qualify as a humanitarian intervention, the international media took notice. According to the Internet database Factiva, 43 news articles mentioned the report, in publications ranging from the Kansas City Star to the Beirut Daily Star. Similarly, after the abuses of Iraqi detainees at the Abu Ghraib prison were disclosed, the views of Amnesty International and the International Committee of the Red Cross put pressure on the Bush administration both at home and abroad.

As these examples suggest, today's information age has been marked by the growing role of non-governmental organizations (NGO's) on the international stage. This is not entirely new, but modern communications have led to a dramatic increase in scale, with the number of NGO's jumping from 6,000 to approximately 26,000 during the 1990's alone. Nor do numbers tell the whole story, because they represent only formally constituted organizations.

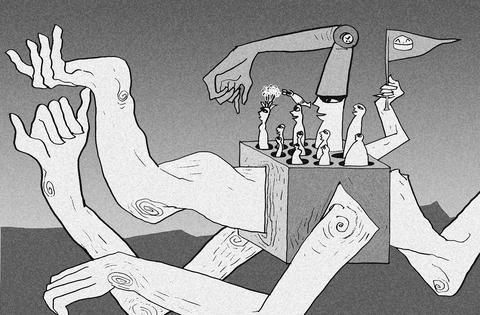

Many NGOs claim to act as a "global conscience," representing broad public interests beyond the purview of individual states. They develop new norms by directly pressing governments and businesses to change policies, and indirectly by altering public perceptions of what governments and firms should do. NGOs do not have coercive "hard" power, but they often enjoy considerable "soft" power -- the ability to get the outcomes they want through attraction rather than compulsion. Because they attract followers, governments must take them into account both as allies and adversaries.

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

A few decades ago, large organizations like multinational corporations or the Roman Catholic Church were the most typical type of transnational organization. Such organizations remain important, but the reduced cost of communication in the Internet era has opened the field to loosely structured network organizations with little headquarters staff and even to individuals. These flexible groups are particularly effective in penetrating states without regard to borders. Because they often involve citizens who are well placed in the domestic politics of several countries, they can focus the attention of media and governments onto their issues, creating new transnational political coalitions.

A rough way to gauge the increasing importance of transnational organizations is to count how many times these organizations are mentioned in mainstream media publications. The use of the term "non-governmental organization" or "NGO" has increased 17-fold since 1992. In addition to Human Rights Watch, other NGO's such as Transparency International, Oxfam, and Doctors without Borders have undergone exponential growth in terms of mainstream media mentions. By this measure, the biggest NGOs have become established players in the battle for the attention of influential editors.

In these circumstances, governments can no longer maintain the barriers to information flows that historically protected officials from outside scrutiny. Even large countries with hard power, such as the US, are affected. NGOs played key roles in the disruption of the WTO summit in 1999, the passage of the Landmines Treaty, and the ratification of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in May last year.

The US, for example, initially had strong objections to the Convention on Tobacco Control, but dropped them in the face of international criticism. The Landmines Treaty was created despite the opposition of the strongest bureaucracy (the Pentagon) in the world's largest military power.

Similarly, transnational corporations are often targets of NGO campaigns to "name and shame" companies that pay low wages in poor countries. Such campaigns sometimes succeed because they can credibly threaten to damage the value of global brand names.

Royal Dutch Shell, for example, announced last year that it would not drill in any spots designated by UNESCO as World Heritage sites. This decision came two years after the company acceded to pressure from environmentalists and scrapped plans to drill in a World Heritage site in Bangladesh. Transnational drug companies were shamed by NGOs into abandoning lawsuits in South Africa in 2002 over infringements of their patents on drugs to fight AIDS. Similar campaigns of naming and shaming have affected the investment and employment patterns of Mattel, Nike, and a host of other companies.

NGOs vary enormously in their organization, budgets, accountability, and sense of responsibility for the accuracy of their claims. It is hyperbole when activists call such movements "the world's other superpower," yet governments ignore them at their peril.

Some have reputations and credibility that give them impressive domestic as well as international soft power. Others lack credibility among moderate citizens but can mobilize demonstrations that demand the attention of governments. For better and for worse, NGOs and network organizations have resources and do not hesitate to use them.

Do NGOs make world politics more democratic? Not in the traditional sense of the word. Most are elite organizations with narrow membership bases. Some act irresponsibly and with little accountability. Yet they tend to pluralize world politics by calling attention to issues that governments prefer to ignore, and by acting as pressure groups across borders. In that sense, they serve as antidotes to traditional government bureaucracies.

Governments remain the major actors in world politics, but they now must share the stage with many more competitors for attention. Non-governmental actors are changing world politics. After Abu Ghraib, even US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld must take notice.

Joseph Nye is dean of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and author of Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Copyright: Project Syndicate

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

After “Operation Absolute Resolve” to capture former Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, the US joined Israel on Saturday last week in launching “Operation Epic Fury” to remove Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his theocratic regime leadership team. The two blitzes are widely believed to be a prelude to US President Donald Trump changing the geopolitical landscape in the Indo-Pacific region, targeting China’s rise. In the National Security Strategic report released in December last year, the Trump administration made it clear that the US would focus on “restoring American pre-eminence in the Western hemisphere,” and “competing with China economically and militarily