Each morning, workers at Alphabet Inc’s Google get an internal newsletter called the “Daily Insider.” Kent Walker, Google’s top lawyer, set off a firestorm when he argued in the Nov. 14 edition that the 21-year-old company had outgrown its policy of allowing workers to access nearly any internal document.

“When we were smaller, we all worked as one team, on one product, and everyone understood how business decisions were made,” Walker wrote. “It’s harder to give a company of over 100,000 people the full context on everything.”

Many large companies have policies restricting access to sensitive information to a “need-to-know” basis.

However, in some segments of Google’s workforce, the reaction to Walker’s argument was immediate and harsh.

On an internal messaging forum, one employee described the data policy as “a total collapse of Google culture.” An engineering manager posted a lengthy attack on Walker’s note, which he called “arrogant and infantilizing.”

The need-to-know policy “denies us a form of trust and respect that is again an important part of the intrinsic motivation to work here,” the manager wrote.

The complaining also spilled into direct action. A group of Google programmers created a tool that allowed employees to choose to alert Walker with an automated e-mail every time they opened any document at all, according to two people with knowledge of the matter.

The deluge of notifications was meant as a protest to what they saw as Walker’s insistence on controlling the minutiae of their professional lives.

The actions were just the latest chapter in an internal conflict that has been going on for almost two years. About 20,000 employees walked out last fall over the company’s generous treatment of executives accused of sexual harassment, and a handful quit over Google’s work on products for the US military and a censored search engine for the Chinese market.

When it was founded two decades ago, Google established an unusual corporate practice. Nearly all of its internal documents were widely available for workers to review.

Employees also had access to notes taken during brainstorming sessions, candid project evaluations, computer design documents, and strategic business plans.

The idea came from open-source software development, where the broader programming community collaborates to create code by making it freely available to anyone with ideas to alter and improve it.

Google has flaunted its openness as a recruiting tool and public relations tactic as recently as 2015.

“As for transparency, it’s part of everything we do,” Laszlo Bock, then-head of Google human relations, said that year.

Google’s open systems also proved valuable for advocates within the company, who have examined its systems for evidence of controversial product developments and then circulated their findings among colleagues.

Such investigations have been integral to campaigns against the projects for the Pentagon and China. Some people involved in this research refer to it as “internal journalism.”

Management would describe it differently.

Last month, Google fired four engineers who it said had been carrying out “systematic searches for other employees’ materials and work. This includes searching for, accessing, and distributing business information outside the scope of their jobs.”

Other employees have said they are now afraid to click on certain documents from other teams or departments because they are worried they could later be disciplined for doing so, a fear the company said is unfounded.

Amy Edmonson, a professor of leadership and management at Harvard Business School, said that Google’s idealistic history increases the burden on its executives to bring along reluctant employees as it adopts more conventional corporate practices.

“It’s just really important that if you’re going to do something that is perceived as change that you’re going to explain it,” she said.

Bock, who is now chief executive officer of Humu, a workplace software start-up, suggested that Google has not succeeded here.

“Maybe Alphabet is just a different company than it used to be,” he wrote in an e-mail to Bloomberg News. “But not everyone’s gotten the memo.”

With assistance from Josh Eidelson

Taiwan’s exports soared 56 percent year-on-year to an all-time high of US$64.05 billion last month, propelled by surging global demand for artificial intelligence (AI), high-performance computing and cloud service infrastructure, the Ministry of Finance said yesterday. Department of Statistics Director-General Beatrice Tsai (蔡美娜) called the figure an unexpected upside surprise, citing a wave of technology orders from overseas customers alongside the usual year-end shopping season for technology products. Growth is likely to remain strong this month, she said, projecting a 40 percent to 45 percent expansion on an annual basis. The outperformance could prompt the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and

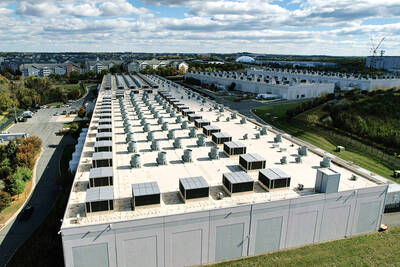

The demise of the coal industry left the US’ Appalachian region in tatters, with lost jobs, spoiled water and countless kilometers of abandoned underground mines. Now entrepreneurs are eyeing the rural region with ambitious visions to rebuild its economy by converting old mines into solar power systems and data centers that could help fuel the increasing power demands of the artificial intelligence (AI) boom. One such project is underway by a non-profit team calling itself Energy DELTA (Discovery, Education, Learning and Technology Accelerator) Lab, which is looking to develop energy sources on about 26,305 hectares of old coal land in

Netflix on Friday faced fierce criticism over its blockbuster deal to acquire Warner Bros Discovery. The streaming giant is already viewed as a pariah in some Hollywood circles, largely due to its reluctance to release content in theaters and its disruption of traditional industry practices. As Netflix emerged as the likely winning bidder for Warner Bros — the studio behind Casablanca, the Harry Potter movies and Friends — Hollywood’s elite launched an aggressive campaign against the acquisition. Titanic director James Cameron called the buyout a “disaster,” while a group of prominent producers are lobbying US Congress to oppose the deal,

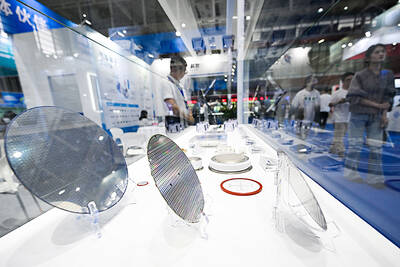

Two Chinese chipmakers are attracting strong retail investor demand, buoyed by industry peer Moore Threads Technology Co’s (摩爾線程) stellar debut. The retail portion of MetaX Integrated Circuits (Shanghai) Co’s (上海沐曦) upcoming initial public offering (IPO) was 2,986 times oversubscribed on Friday, according to a filing. Meanwhile, Beijing Onmicro Electronics Co (北京昂瑞微), which makes radio frequency chips, was 2,899 times oversubscribed on Friday, its filing showed. The bids coincided with Moore Threads’ trading debut, which surged 425 percent on Friday after raising 8 billion yuan (US$1.13 billion) on bets that the company could emerge as a viable local competitor to Nvidia