Whistling a somber tune as he strides through echoing halls, Richard Chang (

The chief of Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC, 中芯國際集成電路) -- a US$1.5 billion foundry symbolizing China's aspirations to become a global chip powerhouse -- lives in company quarters, sports a cheap digital watch and wears a plain plastic name tag.

Chang's unassuming ways belie the hype surrounding the country's chip sector. China is touted as the market of the future, but many analysts say its chip makers still have a long way to go before they can approach the sophistication of Japan or Taiwan.

"China's market is huge, but regarding profits in this business, there are plenty of uncertainties," Chang said in an interview at his factory in Shanghai's eastern financial district, built on what used to be vegetable farmland.

Since construction of their factories began to much fanfare in 2000, SMIC and cross-town rival Grace Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (

Industry experts say SMIC and other domestic operators may initially have trouble securing long-term clients used to Taiwan foundries, and that they could incur high labor costs because of a lack of expert local engineers.

"I think they'll rack up incredible losses in DRAM," a senior executive at a China-based chipmaker told reporters. "They're building production lines, but they have no customers."

SMIC, hoping to prove them wrong, aims for monthly capacity of 40,000 wafers by June, from 32,000 now, making it the country's largest operation. That should shoot to 85,000 wafers by next year.

But Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (TSMC,

"Because China has a huge domestic economy, it can sustain growth in chip demand for very long," said Chang, who set up his first foundry in Taiwan in the early 1980s.

Semiconductor demand in China is likely to grow an average of 16 percent a year and hit US$46.7 billion in 2007, technology research group Gartner estimates.

The country, which uses up to 8 percent of the chips made worldwide, imports more than 80 percent of its chips, signalling huge potential for domestic production to replace that.

Experts say there's no denying the promise, but talk about the inflated expectations inherent in China's ambition to mould itself into a global chip powerhouse.

The industry has come a long way.

David Wang (

It really needed just 500 workers, Wang said. The state firm's schools, hospitals and movie theaters employed the rest.

"The quantum leap in the semiconductor industry really happened back in 1999," Wang said.

SMIC has since become a barometer for the burgeoning chip industry. It has forged deals with Germany's Infineon Technologies AG and Japan's Elpida Memory Inc, and is gunning for a listing sometime late this year or early next year.

"A listing this year might be challenging," Chang conceded.

SMIC has not disclosed its shareholder structure, but Taiwanese investors are believed to hold a significant stake.

It also has financial backing from Goldman Sachs and Shanghai Industrial Holdings.

Now for the bad news. China still lacks many elements essential elements to drive its chip industry -- mass capacity, a viable design industry and a critical mass of the companies that supply the equipment to convert the silicon wafers into chips.

Without those suppliers, global giants like Intel Corp are unlikely to start making chips there.

Most domestic players now make simple chips for appliances and remote controls.

But things could change. TSMC is seeking final approval to set up a US$900-million plant in China, which would be a milestone for the country's chip industry.

"We believe that by 2006, 2008, China will play a significant role on a worldwide basis," said Edward Braun, chief of US chip equipment maker Veeco Instruments Inc.

"We're in the first or second year of a 10-year development cycle," he said. "We need to be patient and allow growth."

Chang says there is another daunting challenge.

"Inertia in government is huge. It's hard to get it moving," said Chang, former boss of Worldwide Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (

"Top leaders are clear what needs to be done, but a lot of lower officials haven't caught up yet," he said.

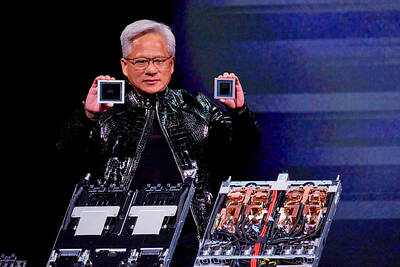

Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Monday introduced the company’s latest supercomputer platform, featuring six new chips made by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), saying that it is now “in full production.” “If Vera Rubin is going to be in time for this year, it must be in production by now, and so, today I can tell you that Vera Rubin is in full production,” Huang said during his keynote speech at CES in Las Vegas. The rollout of six concurrent chips for Vera Rubin — the company’s next-generation artificial intelligence (AI) computing platform — marks a strategic

REVENUE PERFORMANCE: Cloud and network products, and electronic components saw strong increases, while smart consumer electronics and computing products fell Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密) yesterday posted 26.51 percent quarterly growth in revenue for last quarter to NT$2.6 trillion (US$82.44 billion), the strongest on record for the period and above expectations, but the company forecast a slight revenue dip this quarter due to seasonal factors. On an annual basis, revenue last quarter grew 22.07 percent, the company said. Analysts on average estimated about NT$2.4 trillion increase. Hon Hai, which assembles servers for Nvidia Corp and iPhones for Apple Inc, is expanding its capacity in the US, adding artificial intelligence (AI) server production in Wisconsin and Texas, where it operates established campuses. This

Garment maker Makalot Industrial Co (聚陽) yesterday reported lower-than-expected fourth-quarter revenue of NT$7.93 billion (US$251.44 million), down 9.48 percent from NT$8.76 billion a year earlier. On a quarterly basis, revenue fell 10.83 percent from NT$8.89 billion, company data showed. The figure was also lower than market expectations of NT$8.05 billion, according to data compiled by Yuanta Securities Investment and Consulting Co (元大投顧), which had projected NT$8.22 billion. Makalot’s revenue this quarter would likely increase by a mid-teens percentage as the industry is entering its high season, Yuanta said. Overall, Makalot’s revenue last year totaled NT$34.43 billion, down 3.08 percent from its record NT$35.52

PRECEDENTED TIMES: In news that surely does not shock, AI and tech exports drove a banner for exports last year as Taiwan’s economic growth experienced a flood tide Taiwan’s exports delivered a blockbuster finish to last year with last month’s shipments rising at the second-highest pace on record as demand for artificial intelligence (AI) hardware and advanced computing remained strong, the Ministry of Finance said yesterday. Exports surged 43.4 percent from a year earlier to US$62.48 billion last month, extending growth to 26 consecutive months. Imports climbed 14.9 percent to US$43.04 billion, the second-highest monthly level historically, resulting in a trade surplus of US$19.43 billion — more than double that of the year before. Department of Statistics Director-General Beatrice Tsai (蔡美娜) described the performance as “surprisingly outstanding,” forecasting export growth