A trove of files from former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein’s era secretly returned to Iraq has pried open the country’s painful past, prompting hopes some may learn the fate of long-lost relatives, along with fears of new bloodshed.

The 5 million pages of internal Baath Party documents were found in 2003, just months after the US-led invasion that toppled Saddam, in the party’s partly flooded headquarters in Baghdad.

Two men were called in by confused US troops to decipher the Arabic files. One was Kanan Makiya, a long-time opposition archivist; the other was Mustafa al-Kadhemi, then a writer and activist, and now Iraq’s prime minister.

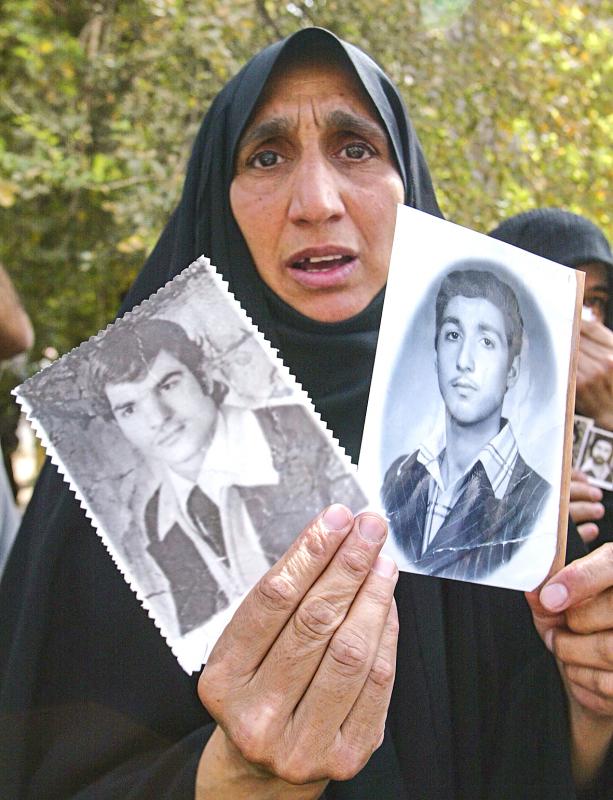

Photo: AFP

“With flashlights, because the electricity was out, we entered the waterlogged basement,” Makiya said by phone from the US. “Mustafa and I were reading through these documents and realized we had stumbled upon something huge.”

There were Baath membership files, and letters between the party and ministries on administrative affairs, but also reports from regular Iraqis who were accusing their neighbors of criticizing Saddam.

Other papers raised suspicions that relatives of Iraqi soldiers taken prisoner during the 1980-1988 war with Iran were potential traitors.

As sectarian violence ramped up in Baghdad after the US-led invasion, Makiya agreed with occupation force authorities to transfer the massive archive to the US, a move that has remained controversial.

The documents were digitized and stored at the Hoover Institution, a conservative-leaning think tank at Stanford University, with access restricted to researchers on-site.

However, on Monday last week, the full 48 tonnes of documents were quietly flown back to Baghdad and immediately tucked away in an undisclosed location, a top Iraqi official said.

Neither government announced the transfer, and Baghdad is not planning to open the archive to the public, the official said.

This could disappoint the thousands of families who might have a personal stake in the archive’s contents.

“Saddam destroyed Iraq’s people — you can’t just keep quiet on something like that,” said Ayyoub al-Zaidy, 31, whose father, Sabar, went missing after being drafted for Iraq’s 1991 invasion of Kuwait.

The family was never given notice of his death or capture, and hopes the Baath archive could hold a clue.

“Maybe these documents are the beginning of a thread that we can follow to know if he’s still alive,” said Ayyoub’s 51-year-old mother, Hasina, who spent the 1990s pleading with the Baath-dominated regime for information on her husband’s whereabouts, and holds little hope of more transparency now.

“At this rate, I’ll be dead before they make them public,” she said.

Some argue the archive could help Iraq prevent its blood-stained history from repeating itself.

“Many kids nowadays say ‘Saddam was good,’” Iraqi filmmaker Murtadha Faisal said.

Faisal was 12 days old when his father was arrested in the holy city of Najaf during a 1991 uprising. He has not been heard from since.

He wants the archives opened to end any rosy nostalgia or revisionism about Baath rule, which some have praised compared to today’s instability under a fragmented political class.

“People should realize how not to create another dictator,” he said. “It’s already happening — we have a lot of small dictators today.”

Divisions over the Baath’s legacy still run deep, and some of its defenders argue the archives would serve to exonerate Saddam’s rule.

“Making the archives public would prove the Baath Party was patriotic,” a former low-ranking party member said.

Those fault lines are precisely what makes the archive’s return a “reckless” move, said Abbas Kadhim, the Iraq Initiative director at the Atlantic Council.

“Iraq is not ready. It has not started a process of reconciliation that would allow this archive to play a role,” said Kadhim, who pored over the documents to write several academic books on Iraqi history and society.

What he found even implicated current officials, he said.

Others say the files could be redacted to make them less inflammatory, but still accessible to local academics.

“The least we can do is have them available to Iraqi researchers the same way they were to American ones,” said Marsin Alshamary, an incoming fellow at the US-based Brookings Institute who also used the archive for her PhD.

Indonesia yesterday began enforcing its newly ratified penal code, replacing a Dutch-era criminal law that had governed the country for more than 80 years and marking a major shift in its legal landscape. Since proclaiming independence in 1945, the Southeast Asian country had continued to operate under a colonial framework widely criticized as outdated and misaligned with Indonesia’s social values. Efforts to revise the code stalled for decades as lawmakers debated how to balance human rights, religious norms and local traditions in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation. The 345-page Indonesian Penal Code, known as the KUHP, was passed in 2022. It

‘DISRESPECTFUL’: Katie Miller, the wife of Trump’s most influential adviser, drew ire by posting an image of Greenland in the colors of the US flag, captioning it ‘SOON’ US President Donald Trump on Sunday doubled down on his claim that Greenland should become part of the US, despite calls by the Danish prime minister to stop “threatening” the territory. Washington’s military intervention in Venezuela has reignited fears for Greenland, which Trump has repeatedly said he wants to annex, given its strategic location in the arctic. While aboard Air Force One en route to Washington, Trump reiterated the goal. “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” he said in response to a reporter’s question. “We’ll worry about Greenland in

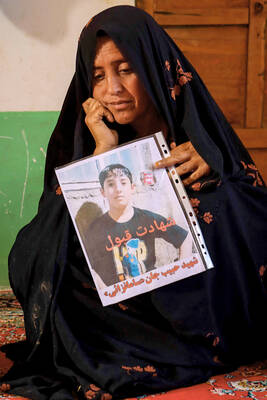

PERILOUS JOURNEY: Over just a matter of days last month, about 1,600 Afghans who were at risk of perishing due to the cold weather were rescued in the mountains Habibullah set off from his home in western Afghanistan determined to find work in Iran, only for the 15-year-old to freeze to death while walking across the mountainous frontier. “He was forced to go, to bring food for the family,” his mother, Mah Jan, said at her mud home in Ghunjan village. “We have no food to eat, we have no clothes to wear. The house in which I live has no electricity, no water. I have no proper window, nothing to burn for heating,” she added, clutching a photograph of her son. Habibullah was one of at least 18 migrants who died

Russia early yesterday bombarded Ukraine, killing two people in the Kyiv region, authorities said on the eve of a diplomatic summit in France. A nationwide siren was issued just after midnight, while Ukraine’s military said air defenses were operating in several places. In the capital, a private medical facility caught fire as a result of the Russian strikes, killing one person and wounding three others, the State Emergency Service of Kyiv said. It released images of rescuers removing people on stretchers from a gutted building. Another pre-dawn attack on the neighboring city of Fastiv killed one man in his 70s, Kyiv Governor Mykola