Eating glutinous rice balls during the Lantern Festival

Lunar New Year celebrations traditionally conclude with the Lantern Festival, which is on the 15th day of the first lunar month. With every household decorated with lanterns and streamers, the Lantern Festival can be seen as an extended New Year celebration.

Lighting lanterns during the Lantern Festival can be traced to the Western Han Dynasty in China. The 15th day of the first lunar month is the first full moon of the year, and has the significance of a new start. People light lanterns to pray for a bumper harvest in the coming year.

Photo courtesy of Ambassador Hotel Kaohsiung 照片:高雄國賓飯店提供

Since the Song Dynasty, the custom of eating glutinous rice balls during the Lantern Festival has taken shape and has been passed down to today. People often associate tangyuan (glutinous rice balls) with two festivals, the Winter Solstice and the Lantern Festival. Eating glutinous rice balls on these two festivals symbolizes the auspicious meaning of family reunion and success in all aspects of life. However, the glutinous rice balls (yuanxiao) eaten on the Lantern Festival are actually a bit different from those commonly seen on the market. The two are often confused, and many people cannot tell them apart. Indeed, many have never eaten real yuanxiao at all.

Yuanxiao or Tangyuan?

Both tangyuan and yuanxiao have glutinous rice as their main ingredient, differing mostly in the way in which they are made. Traditionally, in southern China, tangyuan and yuanxiao are regarded as the same thing, produced by kneading glutinous rice flour and water into a round shape. While the method used in northern China is different — glutinous rice flour is spread on a bamboo sifter, with the stuffing cut into small pieces placed onto the sifter and shaken so that they will be covered in the rice flour, producing the “yuanxiao.” Due to its geographical location and ethnic groups, Taiwan has inherited the southern method of stuffing and rubbing the glutinous rice balls, and these are the glutinous rice balls that we are now familiar with.

Photo: Liberty Times 照片:自由時報

The nature of the fillings differs according to local customs. In addition to the traditional small red and white glutinous rice balls without fillings, there are also bigger rice balls with sweet fillings, and “savory glutinous rice balls” wrapped with meat in Hakka culture. Most of the yuanxiao have sweet fillings such as sesame, bean paste and peanuts. In China’s Zhejiang Province, there are even rose-flavored glutinous rice balls.

(Translated by Lin Lee-kai, Taipei Times)

元宵節為什麼要「吃圓仔」?

Photo: Chen En-hui, Liberty Times 照片:自由時報記者陳恩惠

傳統上,春節要到元月十五的「元宵節」才算正式結束。元宵節家家戶戶張燈結綵,可說是慶賀新春的延續。元宵點花燈的習俗最早可溯自西漢時期,因農曆正月十五是一年當中第一個月圓夜,有著「一元復始」的意味,人們便會點亮花燈祈求整年的豐收。

自宋朝開始,元宵節「吃圓仔」的習俗便漸漸形成、流傳至今,一般人講到湯圓便會直覺地聯想到冬至與元宵節兩個節日;取圓仔的外型、諧音,在這兩個節日吃湯圓都象徵了闔家團圓、諸事圓滿的吉祥意味。不過,元宵節吃的「圓仔」其實跟市面上常見的湯圓不大相同,兩者常常讓人搞不清楚,許多人更是根本沒吃過真正的元宵。

元宵?湯圓?

Photo courtesy of New Taipei City Government 照片:新北市政府提供

湯圓和元宵的主要食材都是糯米,最大的差異在「製作方式」:傳統上,南方把湯圓和元宵視為同樣的食物,是用糯米粉加水揉捏成圓形;而北方的做法則不同,會在竹篩中鋪上糯米粉,再將切成小塊的餡料放入篩中「搖」,在滾動的過程中便會裹上糯米粉,漸漸成形,就是所謂的「元宵」了。台灣因地理位置、族群的關係,自然而然承襲了「搓」湯圓的做法,便是我們熟悉的湯圓囉!

至於是否含有內餡,依照各地習俗有不同的做法,湯圓除了傳統無餡的紅白小湯圓外,也有加入甜餡料的「圓仔母」、客家文化中包了鮮肉的「鹹湯圓」;而元宵多是芝麻、豆沙和花生等甜口味,在中國浙江一帶,甚至還有玫瑰味元宵呢!

(自由時報)

Long before numerals and arithmetic systems developed, humans relied on tally marks to count. These simple, repeated marks — often just straight lines — are one of the earliest and most widespread methods of recording numbers. Archaeological findings suggest that humans began tallying in prehistoric times. During the Late Stone Age in Africa, humans began to carve notches onto bones to create tangible records of quantities. One of the earliest known examples is the Wolf bone, an artifact unearthed in Central Europe in 1937. This bone bears notches believed to be an early form of counting. Even more intriguing

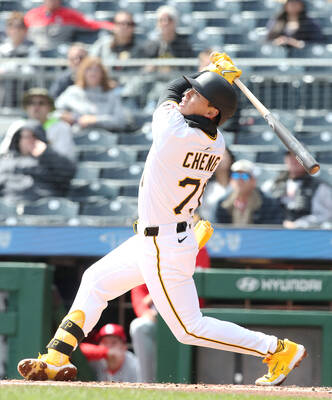

A: In addition to Teng Kai-wei, Taiwanese infielder Cheng Tsung-che was called up temporarily to play for the Pittsburgh Pirates in early April. B: Yeah, Cheng is the 18th player in Taiwan’s baseball history to be moved up to the majors. A: Back in 2002, Chen Chin-feng became the first Taiwanese to play in the Major League Baseball (MLB), followed by Tsao Chin-hui, Wang Chien-ming, Kuo Hung-chih, Hu Chin-lung and Lin Che-hsuan. B: Those pioneers were later joined by Lo Chia-jen, C.C. Lee, Ni Fu-te, Chen Wei-yin, Wang Wei-chung, Hu Chih-wei, Tseng Jen-ho, Lin Tzu-wei, Huang Wei-chieh, Yu Chang,

When Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang revealed on Friday last week that the company is working with the Trump administration on a new computer chip designed for sale to China, it marked the latest chapter in a long-running debate over how the US should compete with China’s technological ambitions. The reasoning has sometimes changed — with US officials citing national security, human rights or purely economic competition — but the tool has been the same: export controls, or the threat of them. Nvidia believes it can eventually reap US$50 billion from artificial intelligence (AI) chip sales in China. But it so far has

Continued from yesterday(延續自昨日) https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/lang In many Western countries, the most common form of tally marks employs a five-bar gate structure: four vertical lines followed by a diagonal slash. To form this group, one begins by drawing four parallel vertical lines, each representing one. For the fifth, draw a diagonal line across the existing four. This diagonal stroke effectively creates a distinct group of five. To continue counting, just initiate a new cycle in the same manner. A set of five tallies combined with a single vertical line next to it represents the number six. Across many Asian countries, the Chinese character