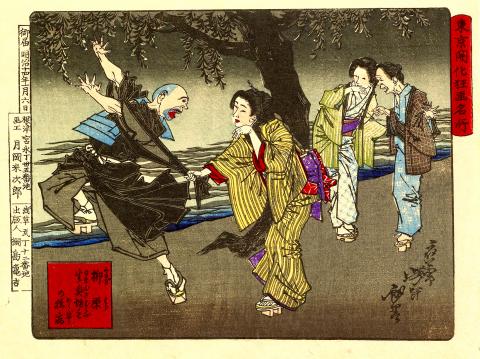

Chinese practice

大驚小怪

make a fuss about nothing

Photo: Wikimedia Common

照片:維基共享資源

(da4 jing1 xiao3 guai4)

有一句古老的拉丁諺語「elephantem ex musca facere」(把蒼蠅說成大象),最早的文獻見諸古羅馬作家琉善的《蒼蠅贊》。把陸地上最大的動物和一隻小昆蟲並列,是比喻把微小的事物放大成很大的東西,也就是指不理性地誇大其嚴重性。此諺語現仍存於俄文中,但在英文裡已不大使用了。

《伊索寓言》中的〈震動的山〉,便使用了類似的並置手法。這故事是說,有一座山開始震動並發出巨大聲響,當地的人便擔心這座山隨時會爆發。他們聚集在一起看著這座山,看看會發生什麼事──有一天這座山終於裂開了,從裡面跑出了一隻老鼠。這故事也傳達了與前段相同的意義:對於無關緊要的小事,別誇大其嚴重性。

一四八四年,英國商人、外交官及作家威廉‧卡克斯頓(西元一四二二~一四九一年)發表了〈震動的山〉的英譯,他說這故事是「山裡一隻鼴鼠讓整個山丘開始顫動和搖晃的寓言」。換句話說,卡克斯頓對這寓言的詮釋是,當地人把鼴鼠打洞在旁堆起的小土丘誤認為是一座山,最後山裡冒出來的不是什麼危險的熔岩,而只是一隻嚙齒動物,如此才真相大白。

尼古拉斯‧尤達爾所編、西元一五四八年出版的《新約聖經伊拉斯謨譯本釋義:卷一》,其中有這麼一句話:「希臘哲人透過擴張性的詮釋,可以把蒼蠅放大成大象、把小土堆放大成一座山」。尤達爾這句話顯然已加進「mountain of a molehill」這個比喻,其靈感可能來自卡克斯頓對《伊索寓言》的解釋。這是「make a mountain out of a molehill」一語首次出現在刊行的書中,沿用至今。它指的是把實為小問題的東西搞得很大。

「make a mountain out of a molehill」的意思,在中文裡可用成語「大驚小怪」來表達。由此語之形式來看,有人或許會認為它的意思是「對小小的奇怪的東西大感驚訝」;然而,這種「大…小…」的構詞形式,其實是中文裡很常見的結構,為的是強調語意──例如「大驚小怪」所強調的是「驚怪」的意思。「驚怪」一詞由來甚久,意思是「驚嘆」;以上述「大…小…」的結構變化後,便成了「大驚小怪」,意指「被嚇倒」(∕被震懾)。宋代理學家朱熹在其〈答林擇之書〉中,談到陶養學問操守的方法,即用了「大驚小怪」一語:「要須把此事來做一平常事看,朴實頭做將去,久之自然見效,不必如此大驚小怪,起模畫樣也」(應該把它看成一件平常事,在日常中踏實地去做,久而久之便會有成效,不需要過分聲張,當成大事般憂心嚴肅地去討論與教導,如此反而無助於事)。朱熹此處用「大驚小怪」來表示「被某事物所震懾」,但他是用否定句來表達。因此成語「大驚小怪」,即是勸人不要把小問題放大成大問題來看。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

拜託,我只不過是燙了個頭髮而已,這有什麼好大驚小怪的?

(Oh, come on, it’s just a perm, why are you making such a big thing of it?)

孩子考差了,就督促他們好好努力下次改進就好了,家長沒必要大驚小怪。

(If their children don’t do well in their exams, the parents need only encourage them to work harder and do better next time: there’s no need for them to make a mountain out of a molehill over it.)

英文練習

make a mountain out of a molehill

There is an old Latin proverb, quoted in Ode to a Fly by the Ancient Roman writer Lucian, that goes elephantem ex musca facere: “to make an elephant from a fly.” The juxtaposition of the largest known land animal with a tiny insect was a metaphor for creating something substantial from something trivial: that is, unreasonably exaggerating its importance. The proverb still exists as a Russian saying, but it has largely gone out of usage in the English language.

A similar juxtaposition was used in the Aesop’s fable The Mountain in Labor, which tells of a mountain that began shaking and emitting loud noises, convincing anxious locals it was about to erupt. They assembled and watched it, to see what would happen, and then one day it split open and out came a mouse. Here, the message is essentially the same: do not exaggerate the importance of inconsequential things.

In 1484, the English merchant, diplomat and writer William Caxton (1422–1491) published a translation of The Mountain in Labor, which he described as a “fable Of a hylle whiche beganne to tremble and shake by cause of the molle whiche delued hit” (a fable of a hill which began to tremble and shake because of the mole inside it). In other words, Caxton was interpreting the fable as saying the local people had mistaken the mountain for a molehill, something that became quite apparent when all that emerged was a rodent-like mammal.

In 1548, The First Tome or Volume of the Paraphrase of Erasmus upon the New Testament, edited by Nicholas Udall, was published, and included the sentence “The Sophistes of Grece coulde through their copiousness make an Elephant of a flye, and a mountaine of a mollehill” (The Greek Sophists could, through their expansive explanations, make an elephant of a fly, or a mountain of a molehill). Here, Udall had apparently added the “mountain of a molehill” metaphor, possibly taking a cue from Caxton’s interpretation of Aesop’s fable. It is the first example in print of the proverb, which has been in use since that time. It refers to making too much of what is essentially a minor problem.

A Chinese alternative to “make a mountain out of a molehill” is the idiom 大驚小怪 (literally “big surprise, small oddity). From the format, it would be easy to suppose that it can be interpreted as meaning “being shocked at something vaguely untoward,” but actually the Chinese construction “大...小...” is a common one, meant to emphasize the word it contains, in this case 驚怪 (to marvel at something). The word 驚怪 is of considerable antiquity, and the phrase 大驚小怪, meaning “to be overawed,” evolved from it. It was used as such by the Song Dynasty Neo-confucian scholar Zhu Xi in his da linze zhi shu (Letter in Response to Lin Ze), in which he wrote concerning the optimal approach to self-cultivation, saying 要須把此事來做一平常事看,朴實頭做將去,久之自然見效,不必如此大驚小怪,起模畫樣也: “If you wish to approach this anxiety-free, practise it on a daily basis and, over time, you will excel at it, and will have no need to be intimidated by it, for this will do you no good.” Here, Zhu Xi is using the phrase to mean “to be intimidated” by something, but he uses it in a negative sentence. The idiom 大驚小怪, then, is a suggestion not to make a fuss of something.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

Why don’t you calm down? You’re making a mountain out of a molehill.

(你冷靜一點好嗎?你這樣根本就是大驚小怪。)

This is no mountain out of a molehill: I don’t think you fully appreciate how serious it is.

(不是我小題大作,是你不了解事情的嚴重性。)

Step into any corner of Turkiye, and you’ll likely encounter the iconic “Evil Eye,” known as “nazar boncu?u” in Turkish. This striking blue glass ornament is shaped like an eye with concentric circles of dark blue, white, and light blue. While its name in English suggests something threatening, it’s actually a charm designed to ward off misfortune. The origins of the nazar boncu?u can be traced back to ancient Mediterranean and Middle Eastern traditions. The word nazar comes from Arabic, meaning “gaze,” while boncu?u translates to “bead” in Turkish. Central to the nazar boncu?u’s mythology is the idea that

A: Wow, Les Miserables Staged Concert Spectacular is visiting Taiwan for the first time. B: Isn’t Les Miserables often praised as one of the world’s four greatest musicals? A: Yup. Its concert is touring Taipei from tonight to July 6, and Kaohsiung between July 10 and 27. B: The English version of the French musical, based on writer Victor Hugo’s masterpiece, has been a huge success throughout the four decades since its debut in 1985. A: The musical has never toured Taiwan, but going to the concert sounds like fun, too. A: 哇,音樂劇《悲慘世界》紀念版音樂會首度來台巡演! B: 《悲慘世界》……它不是常被譽為全球四大名劇之一嗎? A: 對啊音樂會將從今晚到7月6日在台北演出,從7月10日到27日在高雄演出。 B: 這部法文音樂劇的英文版,改編自維克多雨果的同名小說,自1985年首演以來,在過去40年造成轟動。 A:

Some 400 kilometers above the Earth’s surface, the “International Space Station” (ISS) operates as both a home and office for astronauts living and working in space. Astronauts typically stay aboard the station for up to six months and engage in groundbreaking research projects in various fields, such as biology, physics and astronomy. These projects help scientists understand life in space and contribute to advancements that benefit people on Earth. The ISS has experienced significant growth since construction began in 1998. The station’s design and assembly represent an extraordinary international collaboration among Canada, the European Union, Japan, Russia and the United States.

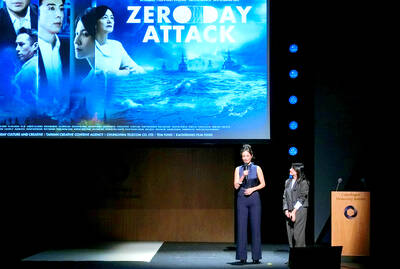

A: While hit musical Les Miserables’ concert tour kicks off, South Korean drama Squid Game 3 will be back at the end of this month. B: New Taiwanese dramas The World Between Us 2 and Zero Day Attack have also gained attention. A: I heard that Zero Day Attack is a story about the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Liberation Army trying to attack Taiwan by force. B: The drama’s subject is so sensitive that it has sparked a lot of controversy in society. A: I just hope that such a horrible story will never happen in