Wu Tsai-li is all business as he leans over a pile of human bones that he’s just dumped on top of a grave, and begins to arrange them back into a vaguely skeletal form.

Wu is in the process of performing a rite of ancestor worship called “picking up the bones.” A part of a ritual generally known as double or second burial, the bones are placed in an urn with the skull at the top. The urn is then re-interred in the ancestral tomb.

Common in Taiwan for over two centuries, the custom has its origins in China’s Fujian Province. When farmers and merchants began migrating to Taiwan in the 17th century, they brought with them their custom of second burial. Over time, the tradition began to spread in Taiwan as it was an inexpensive way of sending the bones back to Fujian for burial in the ancestral tomb.

Photo: Liu Hsiao-hsin, Liberty Times

照片︰自由時報記者劉曉欣

However, as their roots sank deeper into the nation’s soil and people from Fujian began to regard Taiwan as their home, the process of returning the urns to China ceased as family plots were established in Taiwan.

The process, which has changed very little over the centuries, begins with the first burial taking place almost immediately after death. Regarded as a temporary grave, the body remains underground for at least seven years.

The length of time allows the flesh to decompose, making it easier for Wu, a “bone-picking” master, to clean the remaining flesh so that all that is left are the bones. After the flesh is removed, the bones are set out under the sun for three days to dry. They are then “picked up” and placed into the urn, and returned to the family gravesite.

Photo: Liu Hsiao-hsin, Liberty Times

照片︰自由時報記者劉曉欣

If it happens that the flesh hasn’t achieved a level of decomposition suitable for cleaning, Wu sprinkles rice wine over the corpse and dresses it with the leaves of six heads of cabbage. The body is then re-interred. The concoction is enough to ensure sufficient decomposition after an additional three months.

The reason for such an elaborate procedure, Wu says, is that the soul adheres to the bones and not the flesh. This is why the flesh is dispensed with and the bones are re-buried after cleaning.

(Noah Buchan, Taipei Times)

Photo: Liu Hsiao-hsin, Liberty Times

照片︰自由時報記者劉曉欣

吳財立莊重肅穆地俯身向前,面朝著他剛剛倒在墓地上的一堆人骨,開始進行整理,重新排列成一組模糊的骨骸。

吳財立正在進行祭拜祖先的一項儀式,稱為「揀骨」。在這項通常又稱「二次葬」的儀式中,祖先遺骨會被安放在金斗甕中,頭骨放在最上方,再將金斗甕重新葬入祖墳中。

超過兩世紀以來,在台灣廣泛可見的這項習俗,源自於中國的福建省。隨著當地農民與商賈人士在十八世紀移居台灣,他們將「二次葬」的習俗也帶了過來。時光荏苒,這項傳統逐漸盛行於台灣各地。主要的原因在於,當時的先人如果想將祖先遺骨送回福建,葬入祖墳,這種方式並不算昂貴。

Photo: Liu Hsiao-hsin, Liberty Times

照片︰自由時報記者劉曉欣

不過,隨著先人逐漸深入扎根於台灣的土地,來自福建的移民也開始視台灣為家鄉,將金斗甕送回中國的習俗遂逐漸式微,人們也在台灣建起自己家的祖墳。

幾世紀以來,撿骨儀式的過程並沒有太大的改變。首先是一次葬,幾乎在過世後馬上開始進行。接下來遺體會在地下待上起碼七年,這段時間的墳墓則被視為暫時性的。

時間的長度會讓肉體逐漸分解,也使撿骨師傅吳先生更容易清理殘留的身體組織,最後只留下骨頭。徹底清除餘肉後,再將骨頭鋪在太陽底下曝曬三天,進行乾燥,接著便是「撿骨」,放入金斗甕,再重新葬回家族墓園。

萬一發生肉體還未達到適合清理的腐化程度時,吳師傅會在屍身上灑下米酒,再用六顆高麗菜裹住,再度葬回土中。米酒和高麗菜混合的成份足以確保腐化效率,再等三個月後就能重新撿骨。

根據吳師傅的說法,如此複雜的程序,背後原因在於靈魂附著於骨骸而非肉體上。這也就是為什麼肉體最後會被捨去,而骨骸則會在清理後重新下葬。

(台北時報章厚明譯)

Every February, the US observes Black History Month, a time dedicated to recognizing the contributions, experiences, and achievements of African Americans. The tradition began in 1926, when historian Carter G. Woodson proposed a national week to promote the teaching of Black history in schools. He deliberately chose the second week of February to honor the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, two figures held in high esteem by the Black community for their roles in ending slavery. In 1976, the initiative expanded into a month-long observance, with then US president Gerald Ford urging Americans to acknowledge the accomplishments of

★ Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 The fog came before the knock. It covered the street and pressed against the window. Chao Gung-dao lit a small oil lamp, but his makeshift hut stayed dim. Another knock. Chao opened the door. The inspector stepped inside and removed his hat. He did not smile. “You remember me?” the inspector said. Chao resented the question. The inspector looked around the small room. His eyes stopped on a wooden box resting on a low beam above Chao’s head. “What is that?” Chao stayed silent. The inspector pulled the box down and

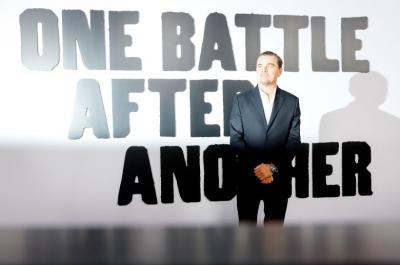

A: The Oscars are set to take place next weekend. It’s a pity that the Taiwanese film “Left-handed Girl” got snubbed. B: And this year, the horror film “Sinners” broke the all-time record with 16 nominations, followed by “One Battle After Another” with 13 nods. Both are nominated for Best Picture. A: What are other Best Picture contenders? B: The nominees are: “Bugonia,” “F1: The Movie,” “Frankenstein,” “Hamnet,” “Marty Supreme,” “The Secret Agent,” “Train Dreams” and Norwegian film “Sentimental Value.” A: It’s so hard to choose from. Some of them haven’t been released in Taiwan yet. I hope they’ll be released soon. A: 本屆奧斯卡獎下週即將揭曉,可惜國片《左撇子女孩》未入圍。 B: 恐怖片《罪人》共獲得16項提名,打破影史紀錄。《一戰再戰》則獲得13項提名緊追在後,都是最佳影片大熱門! A:

對話 Dialogue 清清:今天是元宵節,你晚上有什麼節目? Qīngqing: Jīntiān shì Yuánxiāo jié, nǐ wǎnshàng yǒu shénme jiémù? 華華:我家人要一起去參加臺北燈節,這次有兩個展區,週末我們去了西門的,今晚要去花博的。你呢? Huáhua: Wǒ jiārén yào yìqǐ qù cānjiā Táiběi Dēngjié, zhè cì yǒu liǎng ge zhǎnqū, zhōumò wǒmen qù le Xīmén de, jīnwǎn yào qù Huābó de. Nǐ ne? 清清:我週末去看了今年在嘉義舉辦的臺灣燈會,人山人海,超級熱鬧。 Qīngqing: Wǒ zhōumò qù kànle jīnnián Jiāyì jǔbàn de Táiwān Dēnghuì, rénshān rénhǎi, chāojí rè’nào. 華華:有什麼特色?能吸引那麼多人。 Huáhua: Yǒu shénme tèsè? Néng xīyǐn nàme duō rén. 清清:除了馬年主燈外,今年還有跟任天堂合作推出的「超級馬利歐」專區,可以跟遊戲角色互動和照相。 Qīngqing: Chúle Mǎnián zhǔdēng wài, jīnnián hái yǒu gēn Rèntiāntáng hézuò tuīchū de “Chāojí Mǎlì’ōu” zhuānqū, kěyǐ gēn yóuxì jiǎosè hùdòng hé zhàoxiàng. 華華:那就難怪了,馬利歐是我爸媽跟我共同的回憶呢! Huáhua: Nà jiù nánguài le, Mǎlì’ōu shì wǒ bàmā gēn wǒ gòngtóng de huíyì ne! 清清:去嘉義逛得很累,今晚我就在家好好吃碗熱熱的湯圓來慶祝元宵節了。 Qīngqing: Qù Jiāyì guàng de