On the gray-skied morning of Dec. 21, a black luxury series BMW pulled into the parking lot of the oldest residence in Yilan County, a government-designated “historical building” amid the tranquil rice paddies just off Provincial Highway 9.

Wu Ding-guo (吳定國), the 73-year-old founder and CEO of FineTek Technologies, a manufacturer of specialized industrial gadgets called flow meters, had come to pay respect to his ancestor Wu Sha (吳沙), who opened Yilan County to Han Chinese settlement in the 1790s.

“I’ve come here to tell him that it is the solstice, and that winter has arrived,” said Wu, an eighth generation direct descendant of the pioneer.

Photo: David Frazier

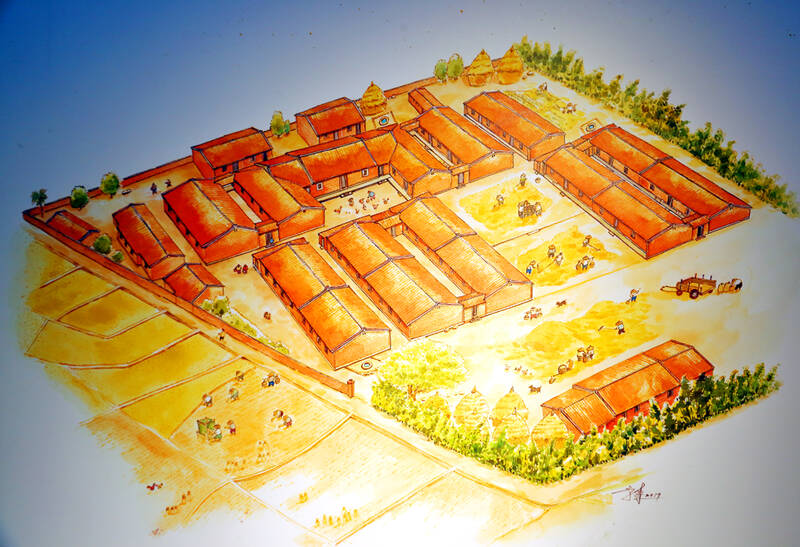

Wu Sha’s residence, a recently restored Fujian courtyard home of pale orange bricks and a tiled roof, had by the early 1800s become Yilan’s de facto administrative capital with a population of 1,000 Han settlers and 2,000 Kavalan aborigines, according to research by the Yilan Wu Sha Cultural Foundation (宜蘭吳沙文化基金會), where Wu Ding-guo serves as chairman.

Even today, a dozen households still live within a compound surrounding the home, all descendants of Wu Sha’s line. The pioneer’s name is everywhere in this little nook of Yilan County. The address plaques on houses read Wu Sha Village. A street vendor’s cart selling Wu Sha spring rolls. The ceremonial gate to the Zelan Temple, which houses the Mazu icon Wu Sha carried over from Zhangzhou, bears the mighty inscription: “Mazu of the Opener of Yilan, Wu Sha.”

“When Yilan was first planned, this area was to be the center,” said Wu Ding-guo, referring to Sijie Township, which is halfway between the hot springs mecca of Jiaosi (礁溪) and Yilan City.

Photo: David Frazier

But between 1807 and 1811, when the Qing Dynasty planned Yilan’s first yamen, or government office, “to suppress the Wu Sha family, the location was shifted further south to the current location in Yilan City. They wanted to establish a new political center.”

CLAN HISTORY

Wu’s interest in his clan’s history began about 25 years ago, when he and his three brothers came to realize that their family lineage was not only crucial to the Han settlement of Yilan County, but that its reputation was also in need of rectification.

Photo: David Frazier

From the early 1810s, official Qing reports disparaged the powerful family’s reputation and whitewashed its accomplishments. The Qing even brought in an outside heir named Wu Hua (吳華), whom they claimed to be Wu Sha’s nephew, to serve as a top minister under the mandarin.

The Wu Sha foundation’s research however indicates the nephew was an imposter, stating “he was not a member of the Wu Sha clan” and describing him as “a political pawn of the then-Qing government.”

“Our family has suffered three persecutions,” Wu said, referring to various land seizures during the past 200 years. “The first time was during the Qing Dynasty. The second time was when the Japanese came. The third time was when the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) instituted land reform. Often these were for the greater good, but for our family, it was not always so good.”

Around 2000, Wu and his family began restoring the Wu Sha Residence — sometimes room by room as family members passed away or moved out — into a small but fascinating museum. The building dates to 1902, when Wu Sha’s fifth generation rebuilt the homestead after the Japanese burned it down.

The interior houses a family altar and historical displays, including a replica of a small cannon or musket used to defend settlements from bandits, rare Qing-era documents, agricultural implements and, most crucially, a remarkable history of the early days of Yilan’s settlement.

Wu Ding-guo began pouring resources into this historical research after establishing the Yilan Wu Sha Cultural Foundation in 2013. Enlisting the help of local scholars, he scoured the archives of Taipei’s National Palace Museum, various Beijing museums, Tokyo’s Althea University, Stanford University in the US and the Institute of Yilan County History. Through Japanese newspaper articles, local records, and official missives to the Qing emperor called zouzhang (奏章), or memorials to the throne, they discovered a string of often oblique references that has helped them piece together Wu Sha’s story.

“After collecting all these materials, I was finally able to see and understand why and how he came here.”

SEEKING A BETTER LIFE

Wu Sha was born in 1731 in Zhangzhou, a prefectural capital in Fujian Province and a major trading center. Population pressure was sending waves of settlers to Taiwan, and in 1773, Wu Sha sailed, along with his wife and two sons, across the Taiwan Strait to seek a better life.

After landing in an already teeming Tamsui, the clan sought out their own homestead, following the mountain valleys east of Taipei until they came to a “wilderness” south of Keelung — Sandiaoling (三貂嶺) in today’s New Taipei City.

There, Wu, a practitioner of martial arts and traditional medicine, recruited and trained his own militia. As the village strongman, he forged amicable relations with the indigenous communities that controlled the surrounding mountains, learning their language and engaging in trade.

The security Wu carved out of his rugged valley took on great importance a decade later, when in 1786, a major rebellion engulfed much of Taiwan.

The insurgency was launched in retaliation for the jailing of a member of a pro-Ming Dynasty triad. The nephew of the accused, Lin Shuang-wen (林爽文), murdered the Qing-appointed Governor of Taiwan, Sun Jing-sui (孫景燧), then rallied a militia that swelled to around 50,000 and, at its height, occupied much of southern Taiwan.

It took the Qing two years and more than 20,000 troops to put down the insurgency and execute its leaders. In the wake of this unrest, a major ethnic feud swept Taiwan that saw Quanzhou settlers ruthlessly attacking those from Zhangzhou — the homeland of not only Lin and many of his insurgents, but also Wu Sha. In parts of Taiwan, entire villages were forced to flee.

Wu Sha’s safe haven in Sandiaoling absorbed around a thousand of these Zhangzhou refugees. The village headman also assisted Qing officials in hunting down Lin’s remaining revolutionaries, thereby cementing his position in the government’s good graces. But the influx left Sandiaoling wanting for elbow room.

Yilan, an expansive, alluvial plain of rich farmland behind a range of high mountains to the southeast, was already known to the Han. But it was still controlled by the Kavalan indigenous peoples and, owing to prohibitions from the Qianlong Emperor in Beijing, no Chinese had yet settled there.

After the emperor died in 1796, Wu Sha saw his chance to make a move. His clan financed a seaborne expedition to Yilan’s northernmost natural port, Wushi Harbor (烏石港), which is still a major center for fishing and tourism today.

Upriver, they built a mud fort at a settlement they dubbed Touwei, meaning the “first walled town.” Today the town is known as Toucheng Township (頭城), or “first city,” and is home to Yilan’s oldest temple, the Qing Yuan Temple, or “first temple of the Qing.”

Wu Sha’s initial settlement at Touwei didn’t last long. The indigenous Kavalan took up arms against the Han invaders and drove him back to Sandiaoling.

But just a year later, a major epidemic — possibly smallpox, according to the Wu Sha Foundation’s research — decimated the Kavalan.

According to the foundation, Wu Sha and his wife returned to aid the be-plagued aborigines, using their knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine to save hundreds of lives. In gratitude, the Kavalan allowed them to settle.

Other accounts however allege that Wu Sha killed the Kavalan and forced them off their lands, effecting a migration that pushed the indigenous people to Hualien.

Nine decades later, Canadian missionary George Leslie MacKay lamented the state of the Kavalan in Yilan, writing that “the greedy Chinese would… either by winning their confidence or by engaging them in dispute… rob them of their lands…It sometimes makes one’s blood boil to see the iniquities practiced upon these simple-minded creatures by Chinese officials, speculators, and traders.”

Wu Ding-guo however insists that such abuses only began after the Qing government took over Yilan in 1812. His research shows that the Kavalan, who lived in plains villages near the coast, used Wu Sha’s Han settlers to create a buffer zone between themselves and another warring indigenous group, the headhunting Atayal, who ruled the mountains.

“They lived in harmony,” he said.

The string of settlements pioneered by Wu Sha’s clan, namely Toucheng, Ercheng, Sancheng (“first city,” “second city,” “third city”) and up to Wucheng (“fifth city,” or present day Yilan City) sits along that original settlement axis. The strip is still Yilan’s major transportation corridor, holding both the east coast railway line and Provincial Highway 9. The cities in this zone all have Chinese names, while those in coastal areas have names derived from the Kavalan language.

“This is something that the Qing Dynasty did not study. No one knew about the history before. Only the locals knew,” said Wu Ding-guo.

‘STAY OUT OF GOVERNMENT’

Just one year after Wu Sha made his settlement deal with the Kavalan, he died in 1798 at age 68. He was succeeded by his son Wu Guang-yi (吳光裔), who together with his widow Zhuang Suo-niang (莊梳娘), established the current family hearth at Sijie.

Guang-yi became a major force in Yilan’s early governance, administering land partitions among the Han settlers and fending off two pirate attacks — at Wushi Harbor in 1806 and Suao Harbor in 1807 — all before the Qing commenced their administration of Yilan.

“But the Qing Dynasty never recognized Guang-yi, because they were very afraid,” said Wu Ding-guo.

Following the Lin Shuang-wen rebellion, the government was wary of local, populist leaders. Yilan’s first mandarin repeatedly divested the Wu clan of farmland. Then in 1815, after Guang-yi’s name appeared on documents forged by a business partner, he was jailed and summoned for trial in Beijing. As if things couldn’t get any worse, the ship transporting him across the Taiwan Strait sank in a typhoon. He was presumed drowned.

From that day forward, the Wu Sha clan adopted its creed, “the family best stay out of government.”

When I asked Wu Ding-guo about this, he chuckled, “That’s no longer necessarily the case. But we still have a concept that one should avoid the front line [in legal disputes]. It’s better to not get involved.”

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

Last month, media outlets including the BBC World Service and Bloomberg reported that China’s greenhouse gas emissions are currently flat or falling, and that the economic giant appears to be on course to comfortably meet Beijing’s stated goal that total emissions will peak no later than 2030. China is by far and away the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, generating more carbon dioxide than the US and the EU combined. As the BBC pointed out in their Feb. 12 report, “what happens in China literally could change the world’s weather.” Any drop in total emissions is good news, of course. By