Researcher Lu Chien-yi (盧倩儀) says that governments have a duty to ensure citizens’ basic needs are met. However, she’s not been won over by the idea of universal basic income (UBI) — regular, unconditional state payments to all — and suggests that one should judge any proposal by the company it keeps.

Neoliberal economists like Milton Friedman and tech tycoons such as OpenAI CEO Sam Altman have expressed support for various forms of UBI, she says, but warns that “They’re not our friends.”

“Their kind of UBI would be used to justify an economic system that features extreme concentrations of wealth and extreme environmental costs,” and rule out any real reforms, says Lu, a research fellow at Academia Sinica’s Institute of European and American Studies.

Photo: AFP/TIME /TIME Person of the Year

By contrast, what she calls a “left wing UBI” would help people “escape from the cage of the so-called ‘free market economy.’” Highlighting the role government contracts have played in building Elon Musk’s wealth and the scale of regulatory capture, Lu scoffs at the idea that the playing field is anywhere near level.

“The market is not an invisible hand,” she says.

Neoliberal supporters of UBI argue that it would provide a safety net without the inefficient bureaucracy and paternalism of a traditional welfare state. Because citizens could make their own decisions and act according to their own priorities, it would encourage individual responsibility and respect consumer choice.

Photo: Fang Pin-chao, Taipei Times

“Right-wing elites have always been very good at appropriating attractive slogans and concepts,” says Lu, who suspects that some UBI proponents on the right have “a vicious hidden agenda to get rid of the welfare state.” Abolishing the tapestry of targeted payments and services that makes up a modern welfare system would reduce citizens’ bargaining power, and make the powerless even more vulnerable, she says.

Many of the ultra-rich, Lu says, “foster a narrative that people are poor because they’re lazy or they lack self-discipline. But it’s the concentration of wealth in their hands that makes others poor. It’s the system, not work ethic, that’s creating inequality.”

Another of her concerns is that UBI would leave those who depend on it exposed to the market, which is “a nice playground for rich people,” but the source of great stress for the many who struggle to meet rent or afford healthcare.

Photo: AP

The proposal made by UBI Taiwan (see the first part of this series in yesterday’s Taipei Times) prompts Lu to ask if, wittingly or not, the group is promoting the kind of universal basic income that would serve the interests of the rich and powerful.

In e-mailed answers provided to the Taipei Times, UBI Taiwan say they “rely on small donations and government subsidies for general funding,” and that they’re not supported by external institutions. They’re preparing to launch a UBI experiment with backing from a fintech company, however, and they hope to get other businesses on board, pitching involvement as a way to fulfill ESG responsibilities or as a social impact initiative.

ENTRENCHING LOW PAY

A common criticism of UBI is that it might entrench low pay and precarious work, by unintentionally subsidizing employers who don’t pay well or promise a minimum number of working hours. But the same is said of certain existing state-funded benefits: In the US, some researchers contend that SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) and daycare subsidies often bridge the gap between low wages paid by employers and the actual cost of living.

UBI Taiwan, which has been studying guaranteed income systems since 2017, acknowledge this risk, but go on to say: “We believe the net effect of UBI is to increase workers’ bargaining power, not depress wages.”

A stable safety net would empower individuals, “giving them the confidence to refuse low wages or poor working conditions, which in turn will drive wages upward.”

Alternatively, UBI recipients could spend time upskilling, pursuing passion projects or engaging in socially valuable activities, such as volunteering.

“This may reduce the labor supply, forcing companies to either offer higher wages to attract employees or invest in automation,” UBI Taiwan says.

As outlined in yesterday’s article, the group believes it’s devised a way to give everyone aged 18 to 35 a guaranteed basic income of NT$15,515 per month without hiking income or corporation taxes, and that there are compelling reasons why this cohort deserves special help.

So far, there’s been no stampede of politicians throwing their weight behind the proposal. The only elected official showing a consistent interest in UBI is Ko Ju-chun (葛如鈞), a Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislator who often talks about technology and its ramifications. UBI Taiwan says it doesn’t want the UBI movement to be linked with any particular party given current political polarization.

UBS VS UBI

Lu thinks a system of universal basic services (UBS) would be more equitable than UBI, and also better for the environment. Providing cash can help people survive, but it often fails to address the root causes of social dysfunction, such as a lack of affordable housing. When organizing healthcare, transportation, and other services, governments can mandate electric vehicles, 100-percent renewable energy and locally-sourced inputs.

Essential services should be part of “the commons,” shared resources and public goods accessible to every member of society, rather than private property or market commodities, she argues. In an ideal world, “they’d be decommodified.”

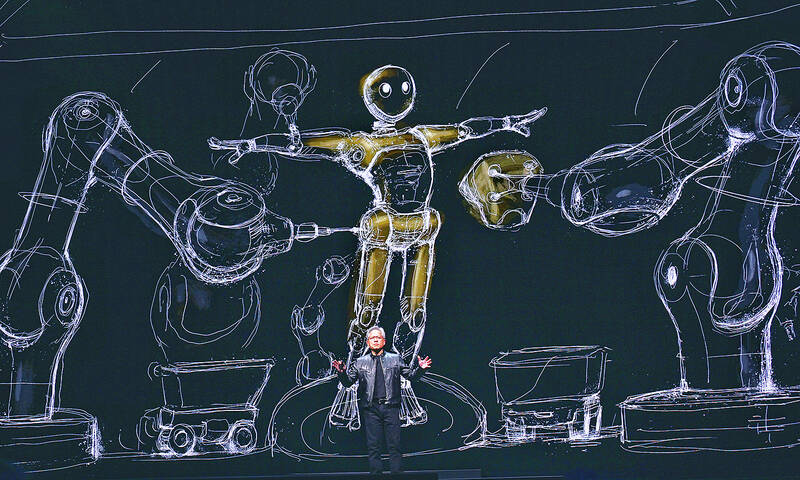

“People in Taiwan are naive about the super-rich and tech firms. They don’t see how harmful these people are,” laments Lu. “You see how they react when Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) comes to Taiwan? Many think that whatever is good for AI, is good for Taiwan. They don’t consider the cost in terms of land, water and energy.”

In Lu’s opinion, AI is already having “a terrible impact. It’s very intrusive, taking our data and privacy, then coming back to train us what to read, see and think. It’s deepening the wealth and power gaps.”

Economic and geopolitical ructions may make life worse for the average person.

“But there are also opportunities for real, systemic progress — so long as we don’t just apply band-aids,” Lu says.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them