Towards the end of Knife, his 2024 book about the assault at a public event in upstate New York that blinded him in his right eye, Salman Rushdie offers a thought experiment:

“Imagine that you knew nothing about me, that you had arrived from another planet, perhaps, and had been given my books to read, and you had never heard my name or been told anything about my life or about the attack on The Satanic Verses in 1989. Then, if you read my books in chronological order, I don’t believe you would find yourself thinking, Something calamitous happened to this writer’s life in 1989. The books are their own journey.”

Extraordinary if true — but though the buoyant surface of Rushdie’s prose has betrayed little overt evidence of his status as the Ayatollah Khomeini’s marked man, the novels nonetheless track his trauma and its aftermaths faithfully. The first he published after the fatwa, 1995’s The Moor’s Last Sigh, begins with Moraes Zogoiby running for his life from unknown “pursuers.” Fury (2001), published after the Iranian president Mohammad Khatami declared the fatwa “finished” in 1998, is transparently the giddy, hyped-up novel of a man set free. Shalimar the Clown (2005) began, as Rushdie tells us, with “a single image that I couldn’t get out of my mind, the image of a dead man lying on the ground while a second man, his assassin, stood over him holding a bloodied knife.” This image, Rushdie says in Knife, was “a foreshadowing.” But it was also a looking backward, at the possible fate that Rushdie was forced to contemplate for years.

“I’m a dead man”: this, he tells us in his 2012 memoir Joseph Anton, was the first thing he thought when he heard the news of the fatwa.

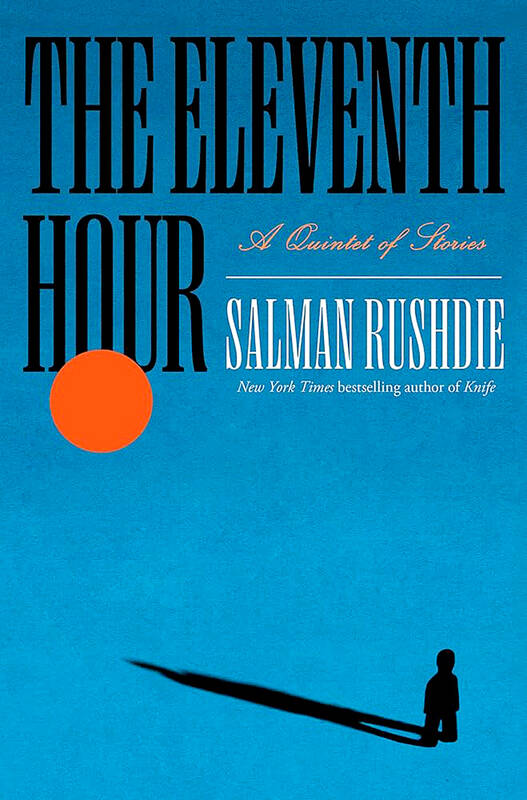

Well, Rushdie isn’t a dead man. He’s still writing. The Eleventh Hour, a collection of five stories, seems intended as a kind of coda to his career. The stories are death-haunted. One of them is called Late; it’s an afterlife fantasy in which a Cambridge fellow, whose career has resembled both EM Forster’s (writing a great novel about India) and Alan Turing’s (helping to crack the Enigma code), dies and haunts a young Indian student named Rosa; what links them may be the buried crimes of empire.

The Musician of Kahani replays Rushdie’s greatest hits: it is about a child born at midnight (“the approved hour for miraculous births in our part of the world”) who, aged four, abruptly becomes a gifted pianist (like the rock star Ormus Cama in The Ground Beneath Her Feet, playing air guitar in his cradle).

These stories are entertaining but not particularly strong. The Musician of Kahana leans pretty heavily on cliche: “the university of life,” “priceless art,” “finger on the pulse,” “the wedding of the year” … In the South is better: a deft, moving anecdote about two old men in Mumbai who bicker and needle one another from their respective verandas. One of them, Junior, dies in an accident. The other, Senior, despairs, until he comes to believe that “death and life were just adjacent verandas.” Oklahoma invokes Kafka; it is a metafiction about a young Indian writer and the older American novelist he admires, or perhaps more than admires — in cases of literary influence, the story seems to ask, who is writing whom?

Rushdie has been one of the deep sources of contemporary fiction. His fingerprints are all over the 21st-century Big Inventive Novel, with its sentient raindrops (Elif Shafak), its melodramatic families (Kiran Desai), its metamorphoses of race (Mohsin Hamid) and history (Marlon James). His influence has not been without its downsides.

Rushdie has licensed lesser writers to be sentimental about their own powers of invention. He has given permission for characters to be flattened into comic stickers. And he has presided over a vast boom in telling rather than showing. The events of his own recent novels, such as The Golden House (2017) and Quichotte (2019), have been relentlessly told, rather than dramatized, and the virus of telling — this and then this and then this! — has noticeably infected the contemporary novel. But Rushdie was a pathbreaker. The exuberance and linguistic force of Midnight’s Children is still, after 44 years, a joy to encounter on the page. Another writer might have been fatally discouraged by what Rushdie has gone through. But Rushdie was not. He wrote the books. And the books, many of them, have greatly mattered.

“Our words fail us,” goes the final sentence of The Eleventh Hour. It is the conclusion of a story about a piazza — a public space — in which language, here figured as a human woman, is courted, usurped, ignored. Finally she screams and vanishes, at which point, the piazza’s buildings all crack: “The piazza is broken, and so, perhaps, are we.”

Words have not yet failed Salman Rushdie, even if, in this self-consciously late book, the spectacular originality of his novelistic peak sounds more as an echo than as an urgently present voice.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word