In Morocco’s High Atlas mountains, shepherds Hammou Amraoui and his son hardly need words to speak. Across peaks, they whistle at each other in a centuries-old language, now jeopardized by rural flight.

“The whistle language is our telephone,” joked Hammou, 59, the elder of a family known for the tradition in Imzerri, a hamlet in the remote commune of Tilouguit, about a two-hour drive from the nearest city.

In Tilouguit, Hammou said people learn it “like we learn to walk or to talk”.

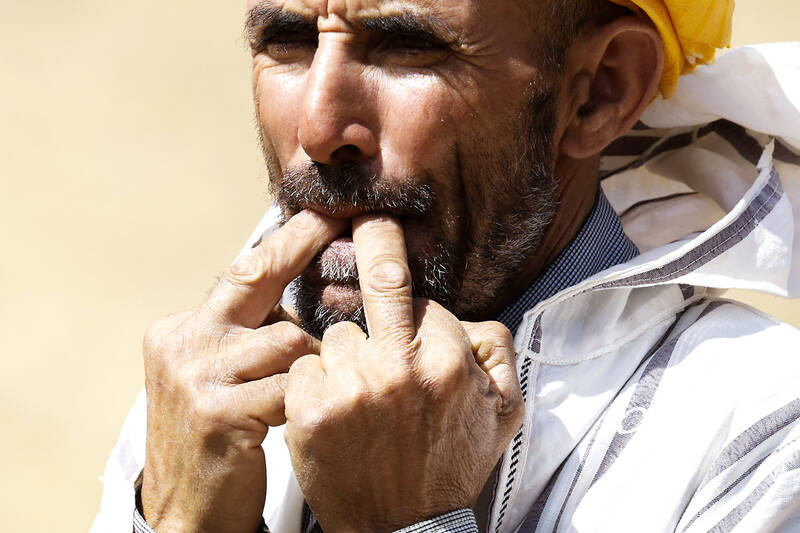

Photo: AFP

The Assinsg language replaces spoken words with sharp whistles that can carry for nearly three kilometers in the mountains, according to researchers.

“The principle of the language is simple: the words are said in whistles and the key to understanding it is practice,” said Hammou’s 33-year-old son, Brahim. “It makes it easier for us to communicate, especially when we’re herding our livestock,” he added. Moroccan heritage researcher Fatima Zahra Salih described the whistle language as a cultural “treasure.”

For five years, she has studied it to prepare a case for its recognition and protection by the UN’s cultural agency UNESCO.

Whistle communication has been documented on nearly every continent, including the Spanish Canary Islands off Morocco’s Atlantic coast.

“A little more than 90 languages have a whistled form, documented in scientific publications,” said Julien Meyer, a linguist who specializes in the phenomenon.

In Morocco, it has so far only been documented in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region of the central High Atlas mountain range, but Salih said she cannot rule out its existence elsewhere.

MOVING AWAY

Getting to Imzerri requires a climb along a dirt track winding through oak trees.

The village counts roughly 50 houses, none with running water or electricity.

Many families have moved away, threatening the survival of the whistle language.

“Our region is magnificent, but we live in isolation and difficult conditions,” said Aicha Iken, 51, who learned to whistle as a child while tending livestock. “Many of our neighbors have left.”

Poverty in Azilal province, where Imzerri lies, has dropped in recent years, but was still double the national average in 2024, at 17 percent.

Yet some families are determined to hold onto their land -- and their whistling tradition.

Brahim Amraoui has made sure his 12-year-old son, Mohamed, was one of the few children in the hamlet who knows how to whistle.

“At first, it was very hard,” said Mohamed, who dreams of becoming a pilot. “I could not understand everything, but after two years it’s getting better.”

His father said it was important to teach him the language, “even if he chooses a different profession”.

“My goal is for the whistle language to be preserved,” he added.

Since 2022, Brahim has led a small association dedicated to safeguarding the practice.

WHISTLE LANGUAGE ‘DISAPPEARING’

It isn’t just the villagers’ migration to urban areas that has put the language at risk of vanishing.

“The whistle language is disappearing little by little because of environmental degradation,” said Meyer.

Drought has gripped Morocco for seven straight years.

In November 2024, for the first time in their history, the Amraoui shepherds left their village to take their livestock on a nearly 350-kilometer journey east in search of pasture. They only came home seven months later.

“The move was painful, but we had no choice,” Hammou recalled. “We had nothing left to feed our animals.”

Salih said it was due to “climate change”, which has “disrupted their pastoral way of life”, where there used to be fixed seasonal pastures near their home they could travel between.

“For the first time, they had to practice nomadism,” she said of the Amraouis.

The shepherd family has pinned its hopes on potential rainfall this fall, hoping they would not be forced to move again.

But while they wonder whether they will have to, Salih insists on the “urgent need to safeguard” the whistle language before more people leave it behind alongside rural life.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

We have reached the point where, on any given day, it has become shocking if nothing shocking is happening in the news. This is especially true of Taiwan, which is in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), uniquely vulnerable to events happening in the US and Japan and where domestic politics has turned toxic and self-destructive. There are big forces at play far beyond our ability to control them. Feelings of helplessness are no joke and can lead to serious health issues. It should come as no surprise that a Strategic Market Research report is predicting a Compound