Jess has never touched a slot machine, played the lottery or bought a scratch-off, but she fears she may have a gambling problem nonetheless.

This July, the 28-year-old found herself spending up to US$270 a week on blind boxes — that is, surprise items that are sold in sealed, opaque packaging. Activewear companies, bookshops and even candy stores all sell mystery bundles of their products, but the brands currently dominating the market produce collectible toys with cute but unusual names. If you want a complete collection of Labubu, Smiski, Dimoo, Pucky, Skullpanda or Sonny Angel figurines, then you will have to buy blind box after blind box, sighing at every duplicate and praying the next package contains the creature you need to finish the set.

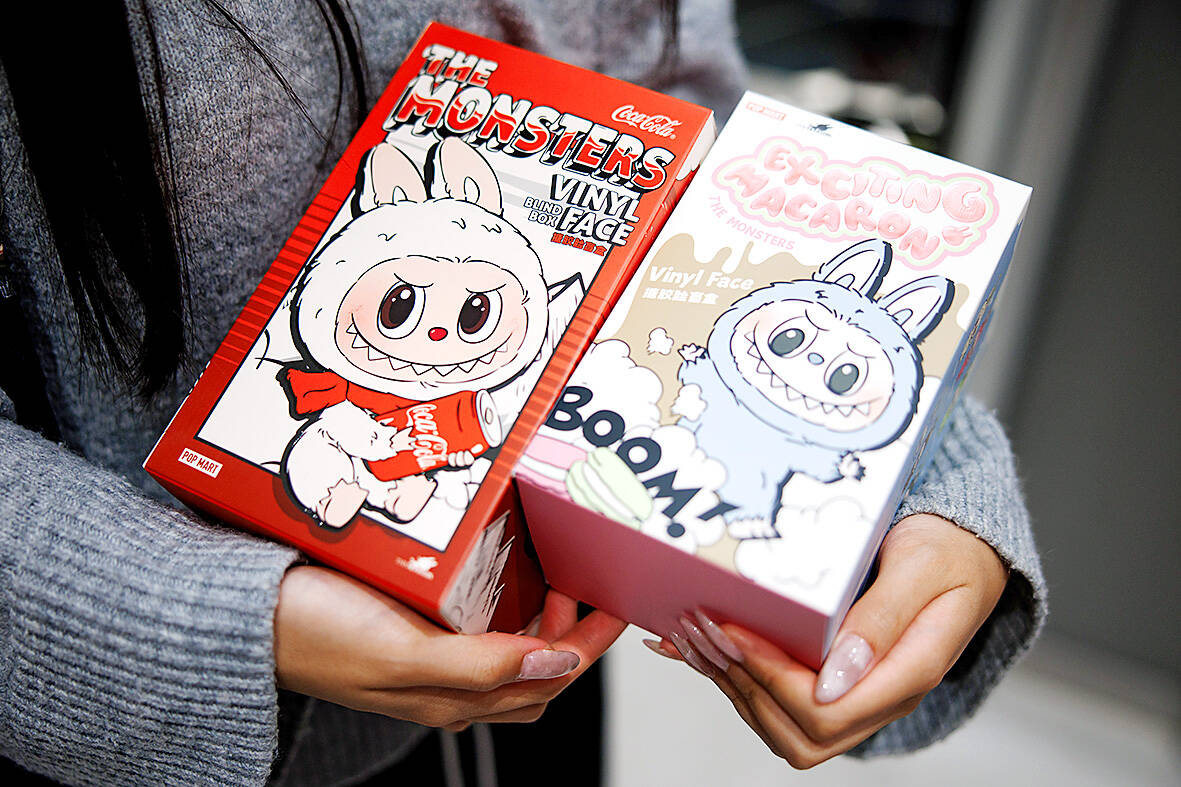

“It’s silly but it is very addictive,” says Jess, who is based in Ireland but prefers not to reveal her full name or occupation. Jess started buying Labubu dolls in April after seeing them on TikTok: these strange, toothsome and fuzzy monsters have exploded in popularity this year thanks to celebrity endorsements and social media hype. Pop Mart, the Chinese company behind Labubus and many other mystery collectibles, is now estimated to be worth US$40 billion — but in June, the company’s stock briefly plunged after a Chinese state media publication condemned blind box marketing as predatory.

Photo: EPA

JESS

Jess believes she is addicted to blind boxes: after she tried banning herself from buying them last month, she “snapped” and suddenly found herself ordering 25 more. Sitting at home and waiting for parcels to arrive, she would itch to go out and physically get some more.

“I would end up buying stuff that I didn’t care about just for the thrill of opening a box.”

Photo: AFP

Jess found herself purchasing mystery plushies from the brand Squishmallows, which she doesn’t even like. “I’d open them and be like, ‘Why do I now have this squishy lobster?’”

Jess says opening blind boxes feels like gambling because of the highs and lows: “Whenever you get the one that you want, it’s unreal.”

On social media, it’s easy to see the impulse buying provoked by blind box marketing. In one TikTok video with 2.6 million likes, a woman buys a US$27.99 Skullpanda, looks at the list of possible toys inside the box and says she would “be happy with any of them” except the Christmas tree dolls. Low and behold, the box contains the Christmas tree, and — visibly frustrated — she rushes back to the store to buy a second box. Another US$27.99 later, she becomes the less-than-proud owner of two Christmas trees.

Photo: EPA

In a different video, a man buys six bags of mystery Disney pins at US$44.99 each, but after ending up with 17 duplicates and an incomplete set, goes back to buy two more, bringing his total spend to almost US$360.

And some buyers don’t just seek the toys they personally like — they also hunt for the “rare” or “secret” items that are more uncommon and thus more valuable.

“The buyer’s guilt that I get nearly every time after I’ve spent is insane,” Jess says, adding that she could have used the money for her forthcoming wedding.

“If it were to continue like this, it would become dire, because who can pop off £1,000 [US$1,300] in a couple of months on literal shit?” Jess says she feels “debilitated” by her habit. “Sometimes I open things and I don’t want them.”

‘KIDULTING’

Dana Nguyen is a 27-year-old from Monterey, California, who has spent US$4,000 on Labubu dolls since the start of this year (on the Pop Mart Web site, Labubu dolls and figurines range in price from US$19.99 to US$959.50 each). Nguyen in April realized she had a problem when she went to her PO Box and saw 20 parcels waiting for her.

“I’m telling myself I want to fly to Europe, I want to travel the world, but how can I do that if I’m spending US$4,000 on fur, cotton, vinyl, whatever these things are made of?”

When asked to describe the feeling she gets when opening blind boxes, she says: “Honestly, that’s gambling. I’m gonna say it flat out: it’s straight gambling.

“I always tell myself I won’t be one of those people in Vegas gambling on the slot machines or on the tables — and then I’m over here doing the exact same thing.”

Adults in America are buying more toys than ever before. In the first half of this year, the number of toys bought for grownups increased 18 percent — and last year, adults bought more toys for themselves than for preschoolers for the very first time. Enthusiasts offer easy explanations for their “kidulting,” summarized neatly in one BBC headline: “Adults buying kids’ toys to escape global turmoil.” As Nguyen puts it: “You’re already struggling as it is, with the economy, with society and you think: OK, let me just have a little sweet treat because I’m not able to afford other luxuries in life.”

Meanwhile, collecting is a very compelling habit. Cary Lee is an Australia-based marketing specialist who researches consumer behavior. Lee has found six main reasons that people collect, including a sense of achievement, an extension of selfhood, community membership and a desire for a legacy. Lee’s studies have shown that the financial motivation to build a collection (for instance, the idea it might be worth something one day) is relatively weak compared with these intrinsic, emotional incentives.

“We have an innate part of us which wants to acquire items to make a collection,” he says.

Toy companies, of course, are well aware of this. In a 2020 prospectus for potential investors, Pop Mart wrote: “While traditional toys are primarily for children to play with, pop toys target young adults between 15 years old and 40 years old in general, who seek for emotional value from expressing personality and attitude.” The company declared itself “relentless” in its desire to “attract and build a fast-growing, young and passionate fanbase” and argued that blind boxes in particular inspire repeat purchases “due to unpredictability and fun.”

DANA NGUYEN

In 2019, Pop Mart asked market research company Frost & Sullivan to survey more than 1,000 consumers and found that, “around 70 percent of pop toy consumers would purchase blind box toys three times or more for a specific toy design they want.”

Lee has conducted studies on blind boxes and has found that most US consumers often come across their first blind box in stores and buy them impulsively. Yet regardless of the outcome — whether they get the toy they like the look of or a dud — people are often compelled to go back and buy another box. One of Lee’s papers uncovered “an addictive loop of impulsive purchases,” arguing there was “a ‘dark side’ to a seemingly innocuous product.”

Online, an oft-repeated defense for the hyperconsumption of collectible toys is: “It makes me happy. It’s not harming anyone” — but is that really true? Beyond the environmental impact — not only are the toys themselves plastic, the packaging is often elaborate and multilayered to add to the thrill of unboxing — there is also personal wellbeing to consider. Nguyen says she initially hid the scale of her spending from her husband (whose business she helps run), and her mental health suffered at the peak of her blind box addiction.

“I have bipolar and I have very manic episodes where I’m willing to take more risks than I normally would,” she says.

After high-energy episodes, sometimes she finds herself irritable and in a low mood.

“You just want a little quick fix. It’s a perfect selling point for people like me who are struggling with their mental health, to just have that little sweet treat, to have that little bit of serotonin or dopamine in their systems.”

Now that she has restricted herself to purchasing fewer blind boxes, Nguyen says: “I feel like my nervous system has calmed a lot more.”

‘GAMBLIFICATION’ OF MERCHANDISE

Eddie is a 34-year-old cashier from Mississippi who recently spent about US$400 on blind boxes in a single month.

“It made me feel sick to my stomach because I didn’t feel like I was in control of what I was spending,” he says. “I’d immediately have buyer’s remorse after making a purchase, and sometimes, I wasn’t even excited to get the package. I was more worried about the damage I’d done to my savings and finances.”

A burgeoning field of study into these gambling-like mechanisms and their impact has researchers concerned. Leon Xiao is an assistant professor at the City University of Hong Kong who researches video game law and the challenges of regulating gambling-like products. Xiao’s work has historically focused on “loot boxes,” which are digital blind boxes sold for real money inside video games. (The items inside often help players perform better in the game.) Yet Xiao is intrigued by the increased “gamblification” of physical merchandise.

“I’ve seen T-shirts being sold in blind boxes, chocolates in blind boxes,” he says.

While Xiao pours cold water on one Chinese study published in 2022, which found that engaging with blind boxes was positively associated with suicide risk in young people — “that’s obviously going too far. There’s also a paper about drinking milk tea or boba linked to suicidal ideation” — he is troubled by other research findings. One longitudinal study published in 2023 found that young people who bought loot boxes participated in more gambling six months later than those who did not. One of Xiao’s own studies has found a correlation between buying mystery card packs and experiencing gambling problems. And a paper published this July argued that loot box spending can be associated with psychological distress and an increased risk of “extreme distress.” Xiao says: “We are concerned about vulnerable people spending more money and experiencing harm.”

Xiao wonders whether new consumer laws might be the answer. In China, a set of advisory guidelines released in 2022 asked companies to publish probability disclosures, set age and spending limits and even implement “pity mechanics” whereby customers are offered the item they desire after making a number of purchases. These guidelines also banned the sale of blind boxes to kids under age eight and required older children obtain parental permission before buying them — but in practice, enforcement is not so stringent.

Defenders of blind boxes note that baseball cards have been around for over a century — and millennials bought mystery playing cards or stickers as kids. Yet, Lee says, what has changed now is the amount of money at stake and how easy it is to spend that money using digital platforms. While a pack of Pokemon cards might have cost a few dollars in the 1990s, most of the blind boxes offered on Pop Mart’s Web site range in price from US$15 to US$26 — though the most expensive one currently available is nearly US$300.

Eddie is now trying to stay away from blind boxes. Nguyen has managed to recoup her money by reselling her collection online during the peak of Labubu popularity, but she still has unpopular ones sitting around that she cannot sell.

Jess faces similar problems — she has tried to sell some of the Labubu figurines she does not like online but has found no one else likes them either.

“They’re definitely not in as high demand as they were at the start of this year.”

Jess is now prepared to sell her toys for half of what she paid for them. Yet although she now has “quite a large collection of stuff and nowhere to put it,” she is still buying more blind boxes. Her ultimate aim is to cut down to one box a month.

Most of the people I speak to would like to see greater regulation of blind boxes, although when I first bring up the idea, Jess admits: “My first reaction was: ‘No! Please don’t take these away from me.’” But she does believe blind boxes are akin to gambling, so suggests there should be “greater warnings about what you could be sucked into.”

“I definitely convinced myself at the start that it wasn’t something that could could hurt me, because of the nature of collecting cute things,” she says. “But it’s very underhanded, how it can affect you without you realizing.”

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South