Aug. 4 to Aug. 10

When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years.

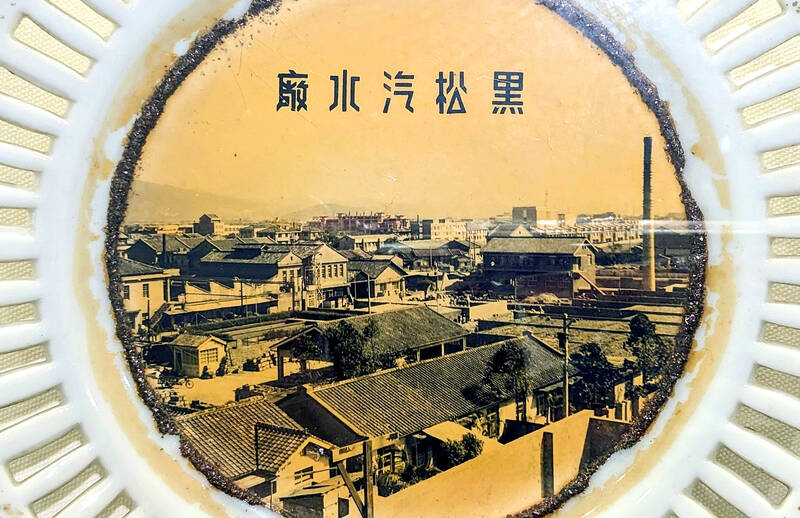

But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s (張文杞) innovative vision and commitment to technical excellence, but also by aggressive marketing strategies that made the brand omnipresent.

Neon towers flashed the logo at tourist sites, rooftop billboards were everywhere and shops displayed its iconic bottle cap signs. Vendors were given merchandise and could use branded fridges for free. Hey Song created soda bottle-shaped puppets and floats for temple festivals and national parades, and even a “soda-pouring robot” built for expos. It also hosted promotional giveaways and radio contests. In 1964, the Hey Song lottery set a national record for prize money.

By the time Coca-Cola arrived, Hey Song was deeply enmeshed in Taiwan’s cultural fabric. It also boasted a flagship drink with a tightly-guarded recipe, Sarsaparilla, prized for its ability to reduce internal heat during hot summer days — especially when consumed with a dash of salt.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

After detailing the history of Coca-Cola in Taiwan last week, this edition of “Taiwan in Time” explores the rise of Hey Song, Taiwan’s home-grown soda empire that withstood the onslaught of foreign imports.

FACTORY IN A COW SHED

Chang Wen-chi (張文杞) was born in 1901 to a prominent family of rice farmers and merchants living in a large courtyard complex on today’s Changan W Road, just north of Taipei Railway Station. Chang also began farming after graduating from elementary school, but his passion for machinery landed him a job as repairman at the Taipei Tobacco Factory, writes Fu Wei-chiung (傅瑋瓊) in The Way of Hey Song over a Century (黑松百年之道).

Photo: Han Cheung

However, due to the low pay, he began selling charcoal and then konjac, a root vegetable. He became fascinated by a neighbor’s soda factory, and often visited to observe. In 1924, a Japanese-run factory that produced ramune — a carbonated soft drink sealed with a marble — put its equipment up for sale, and after discussing it with his elders, Chang purchased the machines. They installed them in the family cow shed and began production on April 14, 1925, at a rate of two bottles per minute. Chang later went to Japan to observe the industry and obtain more equipment.

All three branches of the Chang family pitched in, naming it Chin Hsin Co (進馨商會), with seven cousins serving as shareholders. As chairman, Chang Wen-chi handled technical and product development, while his younger brother Chang Yu-sheng (張有盛) managed sales and marketing as general manager.

Chin Hsin’s first products were Fuji medium-bottle soda and Sanshou marble soda. The Sanshou logo featured three hands, representing the unity of the family’s three branches.

Photo: Han Cheung

Their location was ideal, near the Taisho Railway Station (closed in the 1950s) and close to the affluent Japanese neighborhood of Taishocho, one of the first areas with running water. As the business took off, the courtyard filled with empty bottles. Every night, they boiled a large vat of water to wash the used bottles, and the family would also bathe with that water.

DARK DAYS

Under Japanese rule, soda producers were classified into three tiers: imports from Japan, Japanese-run factories in Taiwan and Taiwanese-owned operations. Third-tiered producers could only sell at low prices and suffered from vicious competition.

Photo: Han Cheung

Determined to show that Taiwanese could also produce high-quality soda, Chin Hsin launched the Hey Song line in 1934, its logo emulating top-shelf sake labels. The name meant “black pine,” a tree favored by the Japanese imperial family, symbolizing evergreenness and longevity. Its most popular drink was the “No-Beer,” a golden, highly carbonated product.

In late 1936, the Changs purchased about 3,500m2 of land (now the site of Breeze Center) to build a new factory. However, due to the Japanese encouraging local soda production in Taiwan, the number of plants surged to the detriment of the industry.

In 1938, the Taipei Prefecture government took control of soda production under its wartime economic policy, collectively running the factories under the Taiwan Cold Beverage Controlled Trade Association. Hey Song lost its autonomy and received less than 10 percent of the profits. Its newly completed factory became the association’s Eighth Factory, with Chang Yu-sheng lamenting: “It’s as if we built the factory just for the association.”

Photo: Han Cheung

As the war went on, the government sought to purchase the factories at unfair prices — this fate was avoided only because Japan surrendered before it could happen.

POST-WAR SUCCESS

Hey Song got its equipment back after the war, but it was virtually bankrupt. It was unable to order more materials or parts as shipping was disrupted, and the carbonic acid plant in Kaohsiung was destroyed by US bombers. The company scraped together what it could and resumed production in July 1946. These postwar years were difficult due to massive inflation and currency reform, but the Chang family kept pumping money into the venture. They soon discontinued the Sanshou line after realizing “three hands” referred to thieves in Mandarin.

No-Beer remained a favorite, as locals often mixed it with rice wine, but the real breakthrough came with Sarsaparilla. In 1947, Chang Wen-chi found a unique-tasting, dark brown soda on a visit to China. He bought the formula and began testing it in Taiwan, naming it after the herb that was believed to cool internal heat and relieve heat stroke. Consumers rejected it at first, comparing it to medicinal syrup, but they warmed up to it after realizing its refreshing properties.

Soda remained a luxury in Taiwan in these early days. People mostly bought chilled lemonade, plum soup and winter melon tea by the cup from roadside vendors. In 1962, a cholera epidemic struck Taiwan, and health authorities found the bacteria in these unregulated drinks — leading to their ban. Vendors then began selling bottled soda in cups instead, and the industry took off.

The company weathered the arrival of Coca-Cola, RC Cola, Pepsi and other foreign brands by upgrading its equipment, refining packaging and continuing its savvy marketing strategy, including memorable television ads targeting young consumers. In 1977, it was the first soda company in Taiwan to use pop-top cans.

Chang Wen-chi died in 1971, and was succeeded by Chang Yu-sheng, who ran the company until his death in 1987. The company continued to diversify its products, and is still run by the Chang family.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not