“I acknowledge we’re losing money,” comedian Jon Stewart told viewers this week. “Late-night TV is a struggling financial model. We are all basically operating a Blockbuster kiosk inside a Tower Records.”

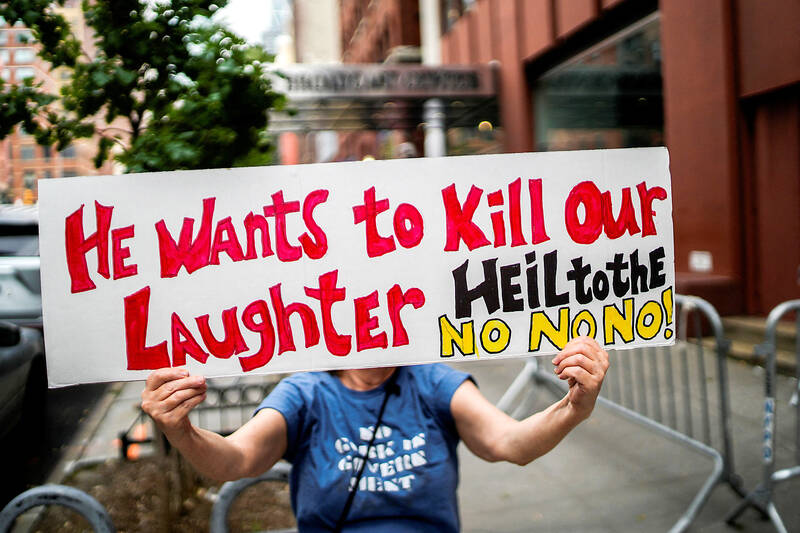

The remark did not dull Stewart’s righteous anger about his friend Stephen Colbert’s show being canceled by CBS after its parent company Paramount settled a lawsuit with Donald Trump — and a week before Paramount’s US$8 billion merger with Skydance was approved by federal regulators.

Stewart did, however, point to another truth about the decline of a format that has been part of America’s cultural fabric for three-quarters of a century.

Photo: CBS via AP

Late-night TV serves a nightly supper menu of comic monologues, variety sketches, celebrity interviews and musical acts. It turned hosts such as Johnny Carson, Jay Leno, David Letterman, Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel, Conan O’Brien and Colbert into a familiar and reassuring presence in millions of homes. It was also relatively cheap to make and offered lucrative returns from advertising, representing a cash cow for major networks.

Stephen Farnsworth, a co-author of Late Night With Trump: Political Humor and the American Presidency, says: “It was a comforting collection of lighter fare before bed. It was for people who work second shifts in factories, people who just wanted a joke or two and a celebrity interview before they drop off. It was a cultural experience back in the days of Carson where you had one show that dominated above all and it had those moments that people would talk about the next day at work.”

STRUGGLING FORMAT

Photo: Reuters

Not any more. The late-night format has been struggling for years as viewers increasingly cut the cable TV cord and migrate to streaming. Younger people are more apt to find amusement on YouTube or TikTok, leaving smaller, aging TV audiences and declining ad revenues. Whereas the Late Show might once have raked in about US$100 million a year, it now reportedly loses US$40 million a year — giving CBS a convenient pretext to pull the plug and claim it was “purely a financial decision.”

Farnsworth, the director of the Center for Leadership and Media Studies at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia, adds: “The big problem with late-night comedy in recent years is the problem with all traditional media in recent years. When you move to an online environment with podcasts and on demand, it’s hard to get people to pay attention in a place where the ad rates are the highest.

“There are plenty of people watching Colbert clips throughout the day on all kinds of platforms. But when you’re talking about advertising revenue, it’s mainly the eyeballs fixed on this TV screen. That’s where the money is made, but it’s also where the decline has been the greatest.”

Photo: Reuters

SPOOF NEWS

The success of Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show, which drew in up to 15 million viewers nightly at its peak, inspired competitors including CBS, which launched The Late Show with David Letterman in 1993. The Daily Show, a spoof news program with mock reporters, began on the cable network Comedy Central three years later.

Under Stewart, the Daily Show gave late-night a satirical edge, exposing the hypocrisy of politicians and the media with lacerating commentary and smartly edited video clips. A spin-off, The Colbert Report, was a searing parody in which Colbert played an exaggerated, bombastic version of a conservative news host and coined the term “truthiness.”

Bill Carter, the author of the book The Late Shift and executive producer of the CNN docuseries The Story of Late Night, says: “Jon Stewart, more than anyone else in that era, brought point of view to what he did, certainly more than Letterman and Leno ever did. Young people loved it. He was breaking news to them. They didn’t pay attention to news; they watched his show and they’d find out things from watching his show.”

David Litt, a former speechwriter for Barack Obama whose books include It’s Only Drowning, says: “What stood out was Colbert’s kindness as an individual and his public persona as an upstanding citizen. That stands in real contrast to Donald Trump. Colbert was the personification of the idea that people who believe in basic decency have a natural inclination toward saying: ‘I want nothing to do with Trump and I have no interest in bending the knee.’

“The Maga frustration with Colbert was you had this person who was a religious Catholic from South Carolina, in many ways not easy to dismiss as a coastal elite or crazy socialist. And what he was saying is that it is deeply American to oppose this man and to find what he’s doing both ridiculous and abhorrent.”

The Late Show became the most watched late-night program with ratings peaking at 3.1 million viewers during the 2017-18 season, according to Nielsen data. But not even Colbert was immune to the tectonic plates shifting beneath the format. In the season that ended in May his audience averaged 1.9 million. The show’s ad revenue plummeted to US$70.2 million last year from US$121.1 million in 2018, according to the ad tracking firm Guideline.

Carter, who has written four books about TV, is not surprised. “It’s of a piece with the end of linear TV,” he says. “The regular primetime programming that’s on the old traditional networks has faded to the point where the ratings stagger me how small they are. It’s like a pond that’s shrinking in the sun. It’s getting smaller and smaller.”

Farnsworth agrees that the shows haven’t failed. The shows have kept up with the changing preferences but they simply don’t get the same advertising revenue online that they do with over-the-air broadcasts.

“These are shows that draw millions of viewers every evening, not to mention millions of more viewers through other platforms. There’s an audience for this. It may not be as big as it was, but no audience is. There’s nothing that television could do to recreate must-see TV or the popularity of All in the Family or M*A*S*H today. People just don’t consume media the same way.”

He concludes: “Ultimately the strategy for the remaining shows is living with less. You’re going to have to figure out ways to cut the staff, maybe air fewer nights a week. This is definitely a warning signal for the genre of late-night humor. But it’s not a death knell.”

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them