Waist-deep in a rain-swollen river, Christer Kristoffersen cast his line, landed it gently on the water, and caught ... nothing. Norway’s iconic wild salmon is in dramatic decline, a victim of fish farming and climate change.

“As a kid, in the early 1980s, there was so much fish in the river, you have no idea. It was packed with sea trout and salmon. We could catch 10 to 15 fish in one evening,” the fly fishing enthusiast said as he stood in the Stjordal river.

Despite decades of experience, the 52-year-old left the river empty-handed 10 days straight.

Photo: AFP

Wild salmon is now so rare that Norway in 2021 placed it on its red list of near-endangered species.

An ever-growing number of wild salmon, which hatch in freshwater rivers before migrating to oceans as adults, are not returning to their birthplace to spawn upstream.

They disappear at sea for as yet unknown reasons, though scientists suspect a link to climate change.

Photo: AFP

Only 323,000 wild salmon swam upstream in Norway’s rivers last year, against one million tallied annually in the 1980s, according to the Norwegian Scientific Advisory Committee for Atlantic Salmon, an independent body set up by the Norwegian Environment Agency.

That has sparked concern among sport anglers and those who make a living from the hobby, which has been part of Norwegians’ DNA ever since English aristocrats brought fly fishing to the country in the 19th century.

“Salmon fishing is very important for Norway, both for the local communities along the river valleys and for the economy and value creation,” said Aksel Hembre, vice president of the Norske Lakselver association grouping those who exploit salmon rivers.

“We attract a great deal of tourism in connection with salmon fishing.”

SEA LICE

Following the drop in the number of returning salmon, authorities last year suspended fishing in 33 waterways and introduced new restrictions this year, including the closure of some rivers, shorter seasons and quotas.

That has been a heavy blow to tourism and the 60,000 to 80,000 sport anglers who indulge in their passion in rivers where the salmon population is considered sufficiently abundant.

While locals can do little about climate change — which leads to warmer waters and changing ecosystems — another culprit is fish farming.

Started in the 1970s, farmed salmon has grown into a US$12-billion a year industry — Norway’s second-biggest export behind oil and gas — and created much-needed jobs.

Norway’s fjords are now dotted with hundreds of fish farms, each of their six to 12 floating cages holding up to 200,000 fish.

According to some estimates, farmed salmon is now a thousand times more numerous than its now-distant cousin wild salmon, due to natural selection.

Farmed salmon contributes to thinning out wild salmon stocks, because of sea lice — a parasite that thrives on fish farms. Some fish also escape from the farms leading to unwanted genetic crossings and diseases, according to the Scientific Advisory Committee for Atlantic Salmon.

When the young wild salmon, known as smolts, swim past the fish farms on their way to the sea, the sea lice “eat their skin, they can suck their blood and eventually they die,” explained the head of the committee, Torbjorn Forseth.

“Cross-breeding between wild and farmed salmon is bad because the farmed salmon is adapted to the farming environment, which is, of course, very different from the wild environment,” he added. “So some of the traits these fish have (such as rapid growth) are very bad for the wild salmon.”

SEALED ENCLOSURES

To eliminate these problems, calls have multiplied for the fish farm cage nets to be replaced by sealed enclosures.

“We demand that there be no emissions, no fish escapes and no impact of lice on wild salmon. This is essential if we want to save it,” Hembre stressed.

While the fish farming industry says it shares concerns about wild salmon, it claims it needs time to adapt.

“The main reason why this is not happening very fast is that it’s quite challenging,” said Oyvind Andre Haram, spokesman for the Norwegian Seafood Association which groups industry heavyweights.

“Just imagine building a closed system, to put it in the ocean compared to an open system. There are a lot of things you have to be aware of,” he said.

“Can anything be broken? Can anything be affected by the streams of the ocean and the fjords? It takes a long time to be 100 percent sure that this is safe,” he said.

The industry has also called for further studies to explain the decline in stocks.

The Norwegian parliament agreed last month that new regulations for fish farming should be introduced within two to four years.

Aimed at reducing the farms’ environmental impact, the rules are expected to push the sector to transition faster to closed cages.

The authorities “are taking baby steps when wild salmon needs a revolution,” lamented Ann-Britt Bogen, who left a career in finance to run a fishing lodge on the shores of the Gaula river. “I’m afraid I’m the last generation who’s going to fish wild salmon in Norway if the government doesn’t take its responsibility.”

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

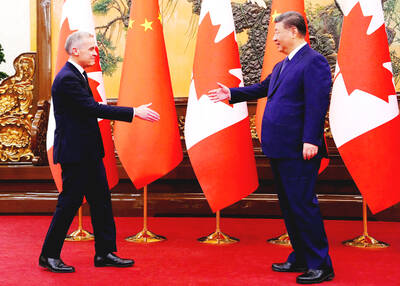

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director