Parents in Japan will no longer have free rein over the names they give their children, after the introduction this week of new rules on the pronunciation of kanji characters.

The change is designed to halt the use of kirakira (shiny or glittery) names that have proliferated among parents hoping to add a creative flourish to their children’s names — creating administrative headaches for local authorities and, in some cases, inviting derision from classmates.

While the revisions to the family registry act do not ban kanji — Chinese-based characters in written Japanese — parents are required to inform local authorities of their phonetic reading, in an attempt to banish unusual or controversial pronunciations.

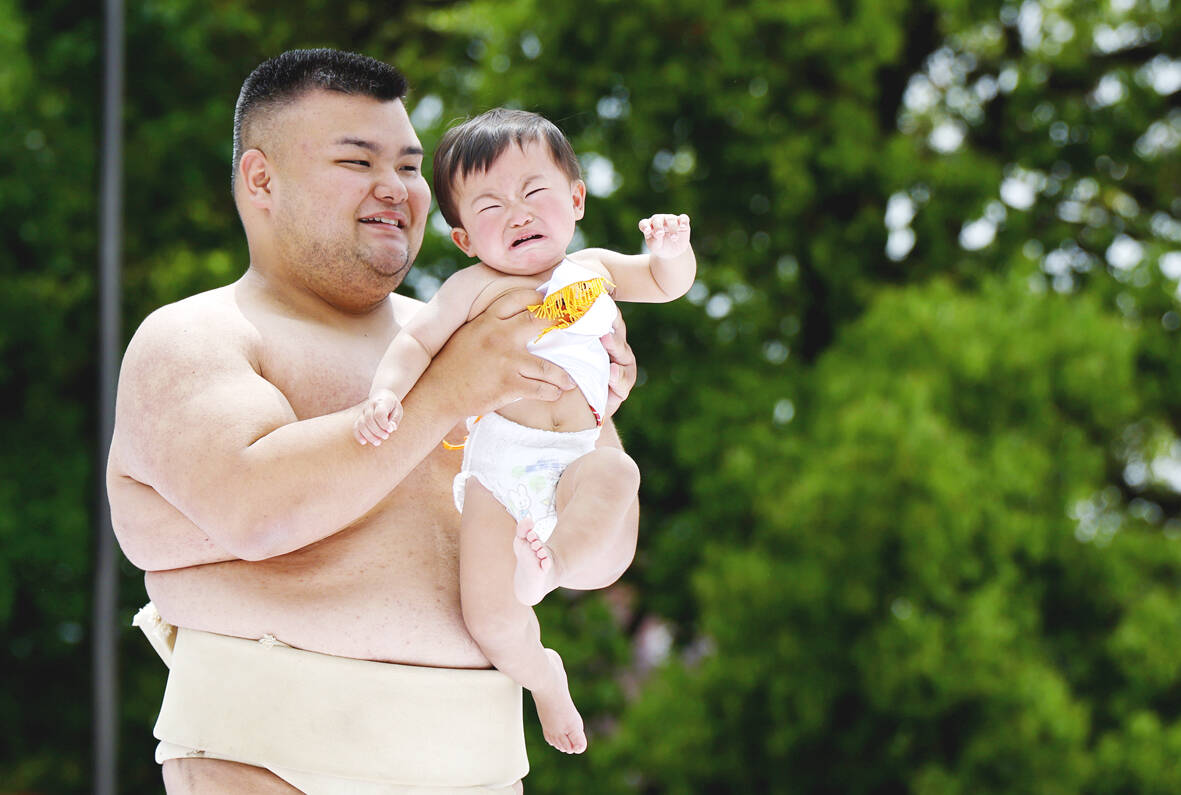

Photo: EPA-EFE

Now, only officially recognized renderings of kanji characters will be permitted, as the government seeks to end the confusion outlandish names can cause in schools, hospitals and other public services.

The debate over kirakira names has been raging since the 1990s, prompted by the rise in monikers based on unorthodox readings of kanji.

The government has described the emphasis on standard pronunciations as a way of simplifying the digitization of administrative procedures, but it is also being seen as an attempt to slow the spread of quirky — and to many, unfathomable — given names.

Parents have been criticized for naming their children after famous characters or brands: Pikachu, of Pokemon fame, Naiki (Nike), Daiya (Diamond), Pu (as in Winnie-the-Pooh) and Kitty, after the fictional feline Kitty Chan. Others have made headlines for their supposed impudence — Ojisama (Prince) and Akuma (Devil).

Seiko Hashimoto, a former Olympic speed skater and track cyclist who later headed the Tokyo 2020 organizing committee, caused a stir when she named her sons Girishia (Greece) and Torino (Turin), because they were born the year the summer and winter Olympics were held in those locations. Having selected the kanji herself, Hashimoto knew how to pronounce them, but others would have been left scratching their heads.

Parents have defended their choices as a show of individual flair in a society where the pressure to conform can be overwhelming, particularly when it comes to raising children.

While most of the 3,000 or so kanji permitted by the revised law have multiple conventional readings, some characters have the linguistic flexibility to accommodate more bizarre phonetics. Shock factor aside, officials have complained that — at first sight — many are simply unpronounceable.

Now, parents who have selected pronunciations that clearly deviate from convention will be asked to explain their choice of name in writing and, if necessary, come up with an acceptable alternative.

While media reports suggest only the most egregious examples will be rejected, the phonetic requirement is a rare change to Japan’s family register, or koseki — a legal record that lists the names and dates of birth of the head of the household, their spouse and their children.

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

A six-episode, behind-the-scenes Disney+ docuseries about Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour and Rian Johnson’s third Knives Out movie, Wake Up Dead Man, are some of the new television, films, music and games headed to a device near you. Also among the streaming offerings worth your time this week: Chip and Joanna Gaines take on a big job revamping a small home in the mountains of Colorado, video gamers can skateboard through hell in Sam Eng’s Skate Story and Rob Reiner gets the band back together for Spinal Tap II: The End Continues. MOVIES ■ Rian Johnson’s third Knives Out movie, Wake Up Dead Man