On the second floor of the Keelung Museum of Art a collection of black-and-white photographs seeks to highlight the city’s layers, from its natural environment to its people.

The exhibition, 26 Seconds of Sun, consists of images taken by Olivier Marceny, a French-born photographer who is based in northern Taiwan.

The title is in reference to a news article that said Keelung only received 26 seconds of sun one winter, in his mind capturing “the moody, atmospheric quality” of the city.

Photo: Lery Hiciano, Taipei Times

Keelung, despite its proximity to Taipei, has a much different feel.

It is smaller, life is slower, international visitors are much less common and its cityscape is dominated by its port and the surrounding hills that nearly envelop the town.

Marceny calls it “a sense of compression,” adding that despite Keelung’s role as a port city and window to the outside world, he felt “a kind of introspective intensity.”

Photo: Lery Hiciano, Taipei Times

Marceny’s professional photography focuses on architecture, and it shows. He has an eye for lines, perspectives, frames within frames and strong use of contrasting colors.

His use of black and white, he said, allowed for “abstraction.”

“It creates distance. It turns the documentary into something more poetic. It helped me focus on form, shadow and texture,” he said.

Photo: Lery Hiciano, Taipei Times

Many of the people in the images have their back to the camera, only providing their anonymous silhouettes for the viewer to project assumptions onto.

In several more photographs, the subject matter is lines, in the form of concrete steps, road markings or buildings coming as close as possible to nature’s edge.

“I was especially interested in the urban fabric built into the hills — how buildings cling to the slopes, the constant presence of stairs and ramps and the way people live in this vertical environment,” Mareceny said.

Most of the photos are grouped in either pairs or triplets, juxtaposed against each other to give rise to a quasi-Kuleshov effect.

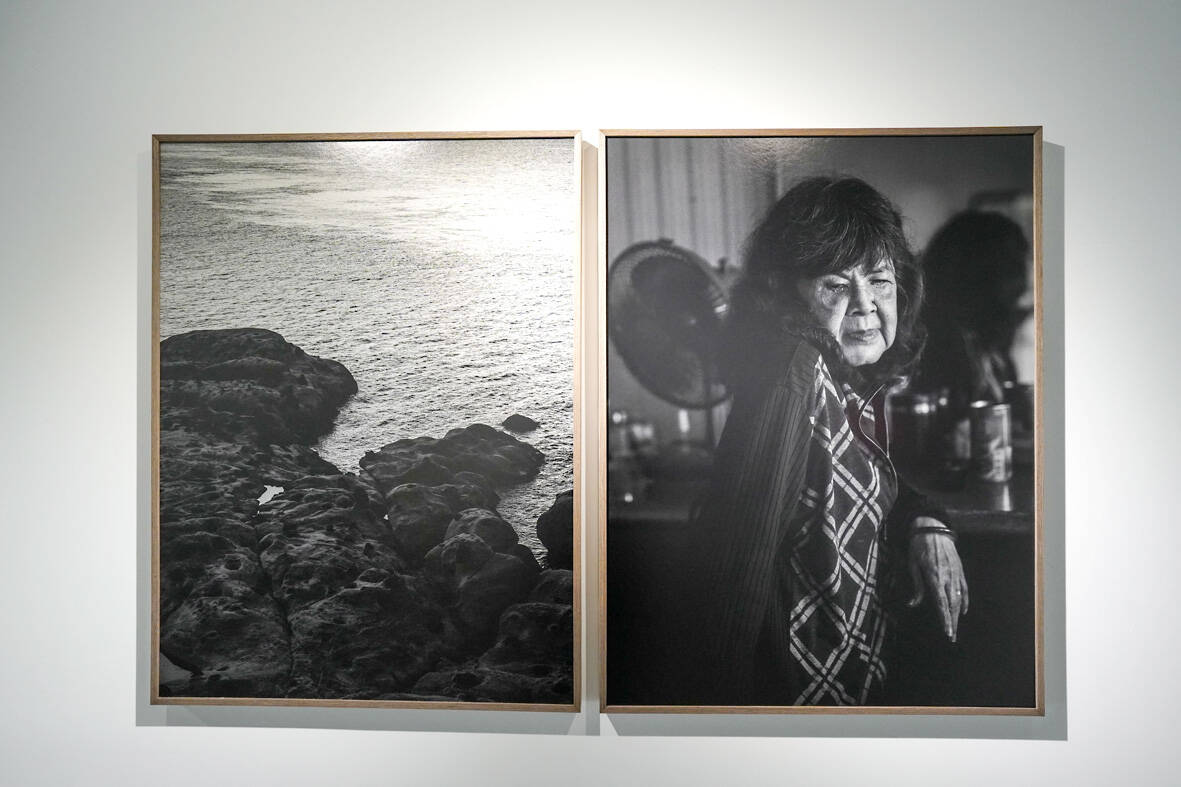

What is the message behind an image of a man on a scooter juxtaposed against a view of buildings climbing into the mountains? Or why is an elderly woman placed alongside a view of the weathered coastline? It is not entirely clear at first sight.

The photos are technically good, reflecting the artist’s skill, yet their meaning is not easily determined.

Some lack frames, only nailed to the walls, others do not seem to have unique subject matter and are unable to stand on their own.

However, hearing from Marceny provided helpful context to his artistic intent and how the collection speaks to Keelung’s “textures” — a word he used several times in describing both his process and the outcome that resulted from it.

When asked about the images’ grouping, Marceny said, “each photo can stand alone, but together they create a rhythm, a kind of visual poetry.”

“By placing images side by side, I aim to suggest small stories or emotional threads — narratives that emerge not from any one photo, but from their interaction,” Marceny said.

One diptych consists of a woman peeking through curtains, while the other a temple incense burner that is nearly translucent compared to the background.

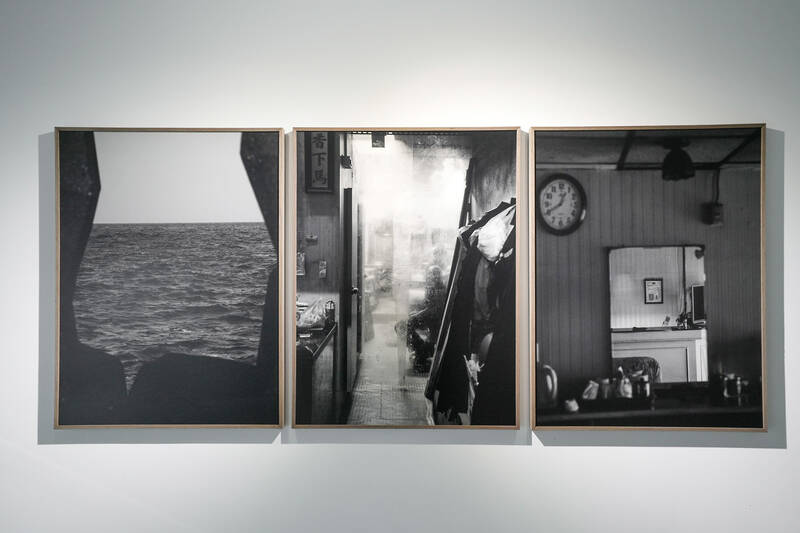

In a nearby triptych, concrete blocks frame the ocean in the first photo, in the second, a man’s silhouette is seen behind a plastic divider, and in the third, a mirror reflects the opposite side of the room to the viewer.

While in these examples, the images’ framing and similarity can help the viewer draw their own conclusions, in other couplets and triptychs the meaning behind them can be opaque.

“Keelung drew me in through its contradictions. It’s a port city, a gateway, a threshold — yet it often feels closed in, almost isolated.”

The connection of the man and his scooter, hemmed in by narrow lanes and closed metal shutters, to the narrow strips of urbanization dwarfed by nature’s expanse, is much easier to intuit with Marceny’s words providing a roadmap.

Although it is impossible to predict, these images may be an important part of the city’s historical narrative.

Keelung is changing. Outside the museum, construction crews add more modern infrastructure, increasing the number of cruise ships arrive and depart and the city may soon see its first MRT system connecting it to New Taipei City and Taipei.

Given all these developments, there may come a time when these urban scenes disappear, or the city’s rougher edges are sanded down for the sake of a newer image.

“With this project, I also intend to retain a memory of that mystery in the dark tones of the prints,” Marceny says, and the viewer has no choice but to agree.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and