March 24 to March 30

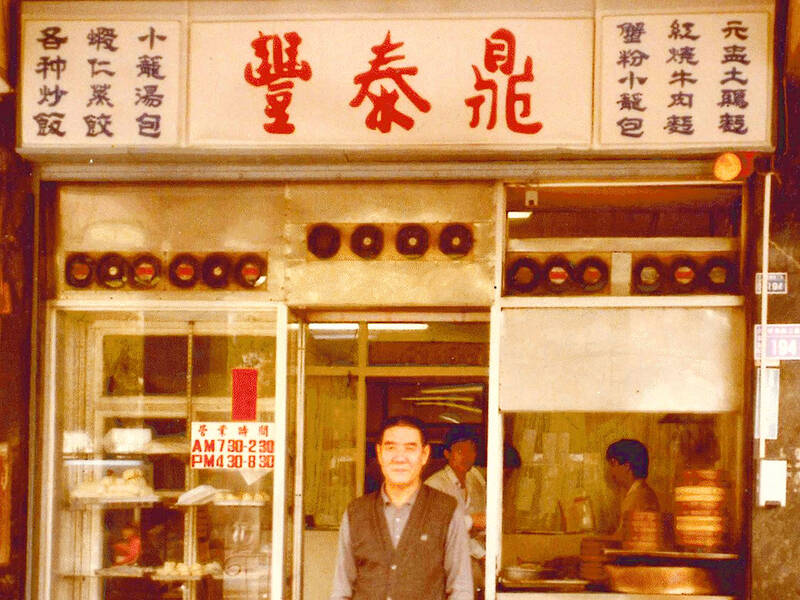

When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐).

The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names.

Photo courtesy of Din Tai Fung

Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and restaurants all over Taipei and Taoyuan. The major Shanghai restaurants in Taipei all ordered from him, and the owners were quite fond of the honest, no-nonsense and hard-working Yang.

In 1963, the couple bought their own shop front, a one-story red brick structure on Xinyi Road (信義路) by Yongkang Street (永康街). Unfortunately, the traditional oil industry took a major hit around 1972 due to a health scare and the advent of mass-produced “salad oil.”

With sales faltering, Yang’s friends suggested that he switch to selling Shanxi specialties such as knife-sliced noodles. However, Tang Yung-chang (唐永昌), owner of Shanghai restaurant Fuxingyuan (復興園), recommended the more delicate, varied Shanghai-style dim sum instead, even setting him up with one of his former dim sum chefs Lu Chi-chung (魯紀忠).

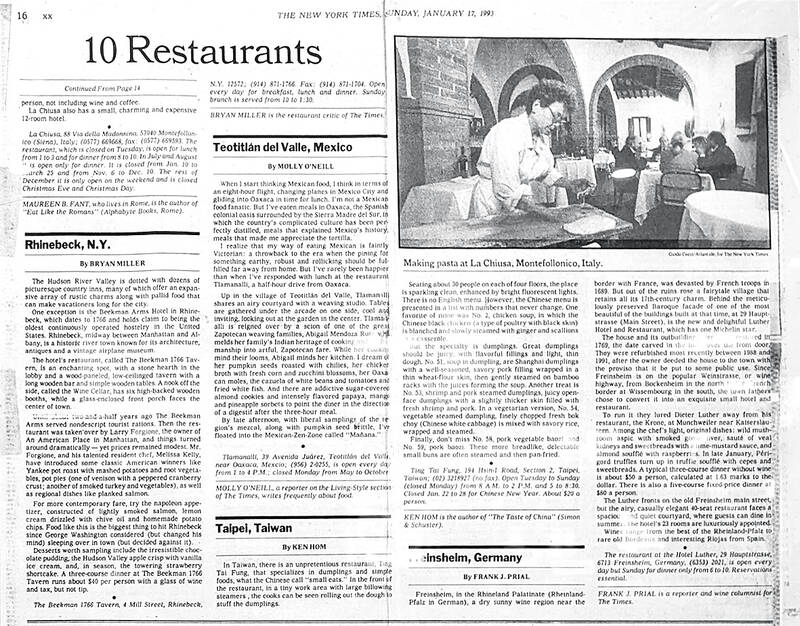

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

In 1972, Yang set up three tables in one-half of his oil shop, and Lu got to work. Business was lousy at first, but Yang persisted, thinking that he had nothing to lose — at that time, he never expected Din Tai Fung (鼎泰豐) to become a global empire.

ESCAPING WAR

Several books provide details on Yang’s early life, including Huang Hung-hu’s (黃鴻湖) Exemplary Din Tai Fung (典範鼎泰豐), Lin Ching-yi’s (林靜宜) Din Tai Fung: Warmth in Perfection (有溫度的完美) and Wang Yi-chih’s (王一芝) You Can’t Learn Din Tai Fung (鼎泰豐你學不會).

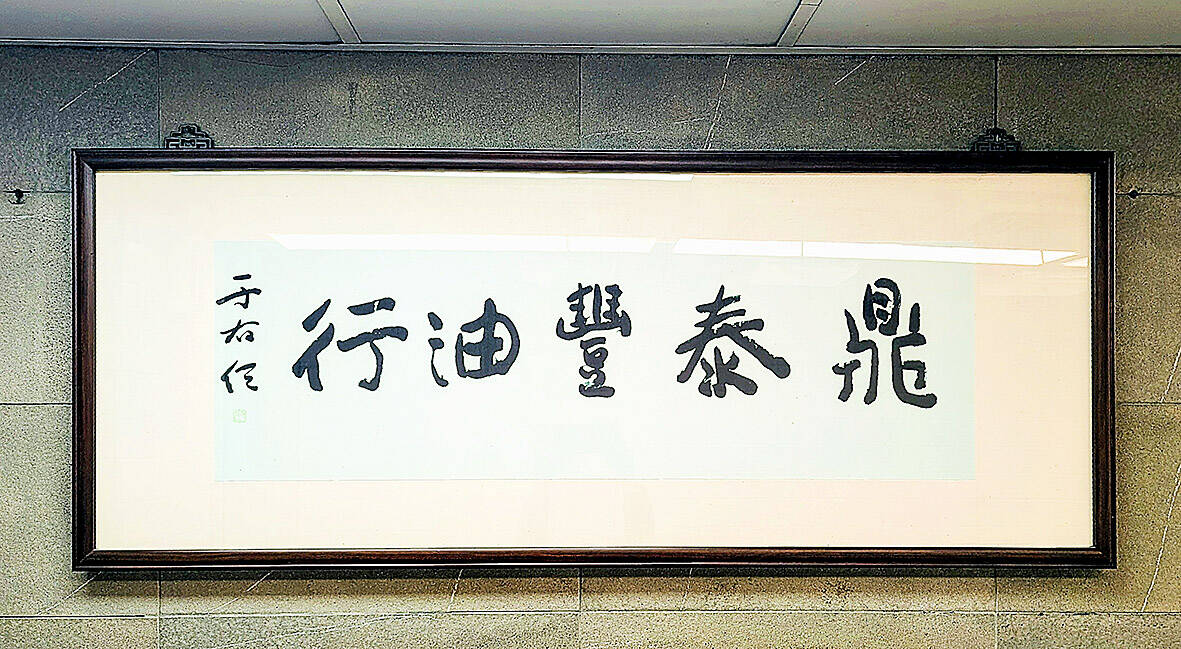

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

He was born Yang Ming-hsing (楊明星) on March 23, 1927 to a scholarly family in a rural village. His hometown was first occupied by the Japanese in 1937 then the Chinese Communists after World War II. He was conscripted and trained by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), but managed to escape.

Yang spent the next seven months in hiding. Growing desperate, he joined Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) general Yen Hsi-shan’s (閻錫山) army in Taiyuan. After seeing how the brigade tortured captured communists, he feared that he would suffer the same fate due to his brief stint in the PLA, so he quit and fled to Beijing, Tianjin and finally to Qingdao, where his uncle lived. Upon seeing that the KMT was also conscripting young men there, he laid low for a month, then boarded a ship with his uncle’s family bound for Taiwan via Shanghai.

The uncle’s wife was from Shanghai, and she helped Yang land a job as a deliveryman for the Shanghainese-owned Heng Tai Feng, which sold soybean, peanut and sesame oil, rice vinegar and bicycles.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Yang worked hard and soon was promoted to store manager and bookkeeper. He continued to work after closing time, delivering wine to all the famous Shanghai restaurants in Taipei for boss Wang’s younger brother. He learned to speak Shanghainese, and became accustomed to their way of living.

OIL FORTUNES

Yang’s birth name simply meant “bright star,” but due to the rise of the film industry, it came to specifically refer to movie stars. People often made fun of it, asking if he wanted to become an actor, so a friend renamed him Bing-yi from a line in the Chinese classic Book of Songs (詩經).

Over time, a romance quietly blossomed with coworker Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹), a Hakka from Taoyuan’s Yangmei Township (楊梅). Lai had other suitors, and her family opposed the union because Yang was a poor mainlander who was six years her senior, which they considered unlucky. The headstrong Lai, however, insisted that their marriage was their private business. In 1955, they chose a wedding date and announced it to the company, much to everyone’s surprise.

Heng Tai Fung prospered until a con-man tricked Wang into a bad investment, and the company collapsed in 1958. Yang opted to remain in the trade, continuing his relationships with the Shanghainese restaurateurs. It was difficult to obtain a phone number then; Yang bought his from Control Yuan member Yang Yi-ta (楊貽達), who was also from Shanxi, and the restaurant still uses that number today. Yang Yi-ta also helped him persuade then-Control Yuan president and master calligrapher Yu You-jen (于右任) to write the iconic characters for the sign.

While Yang was out all day delivering, Lai took the business calls while looking after the house and children. She would become an integral part of the restaurant as the matriarch. Even after the restaurant took off, she could still be seen quietly making wontons in a corner and staying late to do bookkeeping. She is credited for creating some of the side dishes, and Yang was heartbroken when she passed away in 1996.

The business took off after they moved to Xinyi Road, but the good times wouldn’t last. In 1968, the government sampled peanut oil from 23 companies and found that two-thirds of the products contained aflatoxins, greatly alarming the public. Soon, peanut oil producer Chen Shu-yu (陳書友) introduced soybean oil refining technology from Japan, and this mass produced, easy to store and transport “salad oil” dominated the market by 1972.

DUMPLING EMPIRE

Lu ran his half of the shop independently, giving Yang 20 percent of his profits. Two years later, Lu left and sold his equipment to Yang, who then hired Taiwanese dim sum chef Tsai Shui-hsin (蔡水信). Din Tai Fung now occupied the entire storefront, offering many of the staples it still carries today — most notably the xiaolongbao (steamed soup dumplings).

Huang writes that Lu regularly left the store after dinner hours to play a few rounds of mahjong, and he taught Yang Bing-yi’s teenaged son, Yang Chi-hua (楊紀華) to make the dumplings so he could help out. Tsai also did the same, and the younger Yang soon mastered the art, later helping devise the shop’s winning formula with 18 folds in the dumpling skin.

With its generous, masterfully-mixed soup filling, Tsai’s dumplings slowly garnered attention. In 1978, notoriously harsh food critic Tang Lu-sun (唐魯孫) penned an article in United Daily News, praising Din Tai Fung’s crab paste soup dumplings, noting that they did not skimp on the ingredients.

In December 1982, Tang published another article about the dumplings, and this time, the crowds started pouring in. Since Yongkang Street had become a tourist hotspot, the Tourism Bureau mentioned the restaurant in its brochure introducing Taiwan on China Airlines flights, attracting scores of Japanese visitors — especially after Japan-based businessman Chiu Yung-han (邱永漢) wrote about the dumplings in the Nihon Keizai Shimbun newspaper.

By 1988, Yang Chi-hua, who had begun working full time at the restaurant in 1982, had taken over everyday duties, allowing Yang Bing-yi to return to Shanxi to see his mother and surviving relatives for the first time in 34 years. In 1993, Din Tai Fung was featured in the New York Times as one of 10 restaurants that “inspire a pilgrimage,” carrying its fame to the West. Yang Bing-yi retired in 1995 and left the store to his son. He died on March 25, 2023.

Despite numerous offers for the restaurant to expand, both Yangs always refused, worrying that the quality would go down and preferring to put their best effort into one shop. However, Takashimaya department store’s Taiwan head Koutaro Sano was extremely persistent, and finally Yang Chi-hua told him that if they could send staff to Taiwan to train for one year, he would allow it. Takashimaya did so, and finally, Din Tai Fung’s first expansion opened in Japan in 1996 — the first step to global domination.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.