March 10 to March 16

Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label.

Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more popularity.

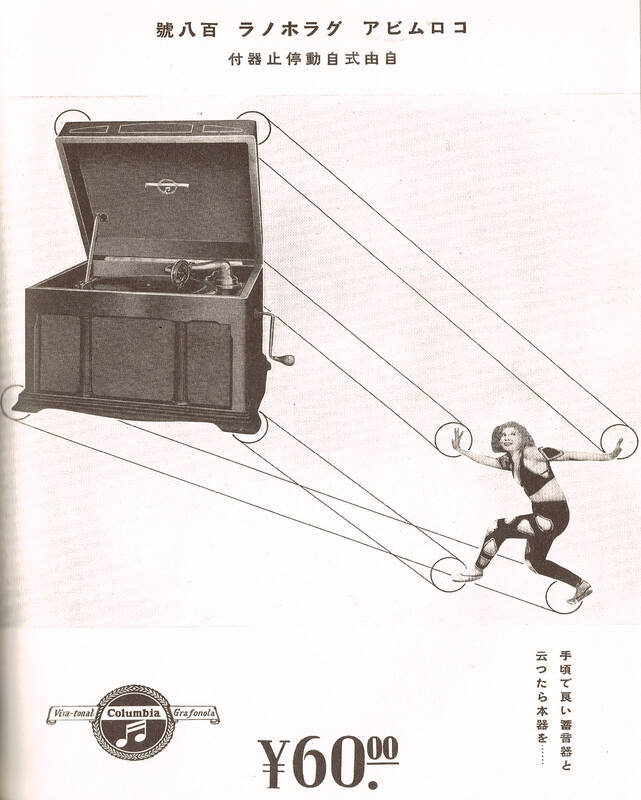

As gramophones became increasingly compact and affordable during the late 1920s — sales jumped by 250 percent between 1925 and 1931 — Japanese record companies became interested in extending their reach to the colony, writes Shih Ching-an (施慶安) in “Study on the record industry and Taiwanese pop songs during the Japanese colonial era” (日治時期唱片業與台灣流行歌研究). Executives such as Columbia’s director Shojiro Kashino knew that they had to appeal to local tastes, closely studying all forms of existing Taiwanese music and theater styles and inviting local performers to recording sessions.

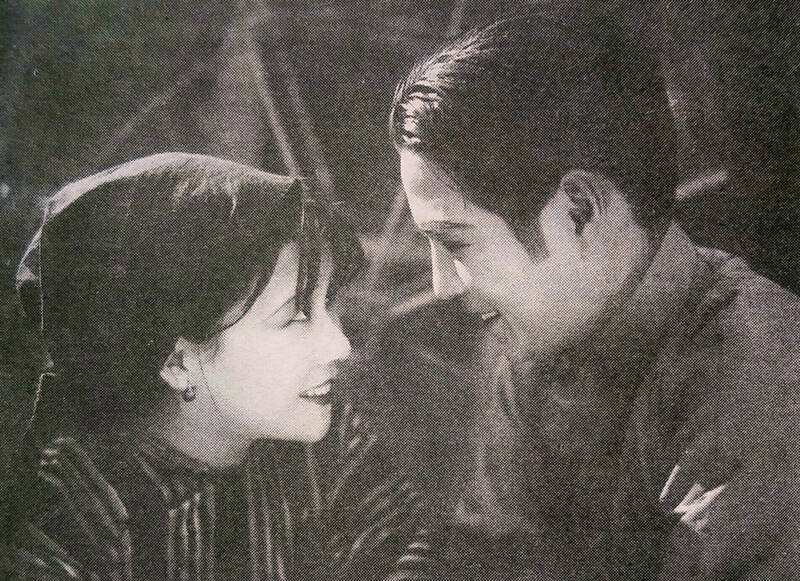

Taiwan’s first hit song appeared in March 1932 as the Taiwanese theme song for the Shanghai film The Peach Girl (桃花泣血記), starring the Chinese icon Ruan Lingyu (阮玲玉). It was written purely for promotional purposes, but it quickly caught on due to the movie’s aggressive advertising. Kashino capitalized on the craze and recorded the song with singer Chun-chun (純純), catapulting Columbia to the top of Taiwan’s record industry. As a result, some scholars consider this Taiwan’s first true “pop song” instead.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Since the tune was essentially an ad, the final lines were “If you want to know what happens next, please watch The Peach Girl!”

ARRIVAL OF THE GRAMOPHONE

Shih writes that the first report of a gramophone in Taiwan was in 1898, when a man from China’s Guangdong Province arrived in Taipei’s commercial center of Dadaocheng (大稻埕) to put on a traditional music show. He made his introduction and the show began, but the audience was astonished that there was sound, and no performers. The reporter for Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) surmised that it must have been a gramophone, which was invented by Thomas Edison in 1877 and was being manufactured in Japan.

Photo: Liberty Times file photo

A year later, another article described how a man with a “machine inside a glass box” stood in front of Qingshui Temple (清水廟) in Wanhua District (萬華), charging passersby to plug the tubes sticking out of the device into their ears. Next to the machine were several boxes that contained round, flat objects, and when placed onto the machine, a needle began moving slowly across it. The writer also gave it a try, and wrote that “it was as if a performer was playing right behind my head. How amazing!”

At first, gramophones were bulky, luxury items that could only be ordered from Japan, but by 1916 they were becoming smaller, more affordable and available in Taipei’s stores.

In 1914, Nipponophone Co, which had established a branch in Taiwan, invited 15 Taiwanese musicians from Hsinchu to record in Tokyo. They are believed to be mostly Hakka, and they made 121 recordings covering the gamut of Han Taiwanese music forms at that time. Most of the material consisted of traditional Hakka “eight-tone” and tea-harvesting songs, but there were also Hoklo nanguan (南管), beiguan (北管), cart-drum opera and gezai (歌仔戲) opera numbers.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Only half of these records have been found, writes Chen Wan-ling (陳婉菱) in “Revisiting Taiwan’s popular music and pop songs under the Japanese-era record industry system” (再訪日治時期唱片工業體制下之臺灣流行音樂與流行歌). Most don’t specify the music style on the label, with “Formosa Song” printed on just a handful of them.

RISE OF TAIWANESE RECORDS

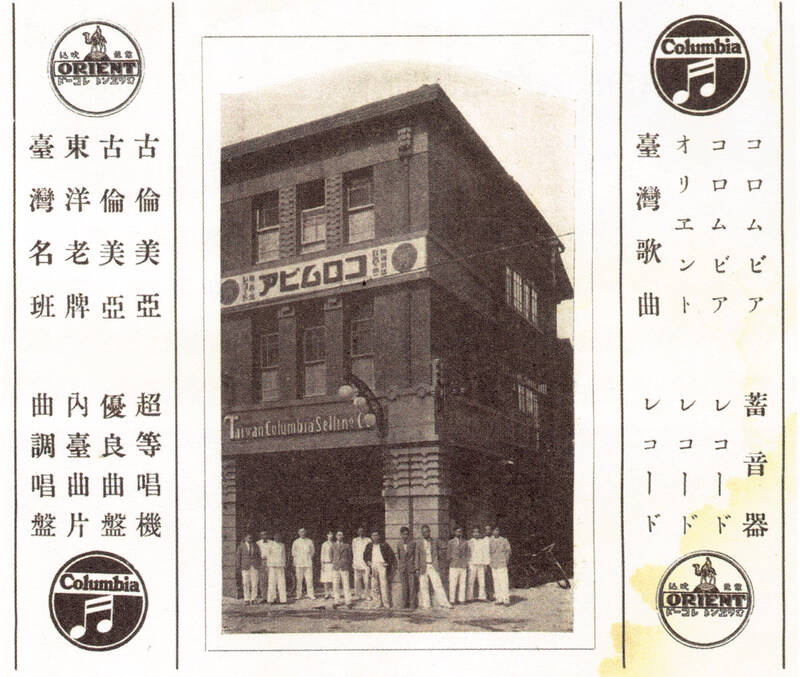

Perhaps due to the lack of commercial success, no more Taiwanese records were made for the next 12 years. By then, Nipponophone had affiliated itself with the US-based Columbia Gramophone Company and began releasing records using the brand name and “magic notes” logo. Another major player had emerged on the scene: Tokyo Record Manufacturing Co, referred to locally as Golden Bird Records due to the mascot that appeared in most of its Taiwan releases.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Music had not changed much over the course of the decade, except for the emergence of gezai opera, Chen writes. The companies also took an interest in indigenous and religious music. The specific musical style of the record was now clearly annotated on each label.

Golden Bird invited a Taiwanese performer to record in Japan in 1926, and a report showed that it planned to set up a studio in Taiwan that summer. In May of the same year, Columbia gathered local musicians for a multi-day session at two banquet halls in Taipei — Shih writes that this is considered the first commercial recording effort in Taiwan.

Chen writes that the phrase “popular music” began appearing in advertisements, but it merely referred to the tunes that ordinary people commonly enjoyed and had yet to refer to a specific style. For example, it was used to describe a gezai opera recording.

PENNING A SMASH HIT

In January and February 1931, Columbia carried out a large-scale local recording project, yielding 224 productions under the Eagle label. March of the Black Cats was among them.

As industry competition heated up, the labels were eager to experiment. Chen writes that March of the Black Cats employed Western instruments, rhythms, harmonization and composition styles, fitting the idea of what is commonly considered a “pop song” today. However, not all similar productions were explicitly labeled as “pop songs.”

The Peach Girl roughly follows the same format, Chen writes. The movie depicted a tragic romance between a wealthy, educated boy and a poor shepherd girl, and espoused freedom of marriage without familial interference.

At that time, licensed Taiwanese benshi (辯士) provided live narration during screenings of silent films. This movie’s narrator, Chan Tien-ma (詹天馬), was charged with penning its local theme song in collaboration with composer Wang Yun-feng (王雲峰). (Chan Tien-ma later established the Tien Ma Tea House, remembered today as the ignition site of the 228 Incident in 1947, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed.)

The movie company hired a team of young women dressed as characters in the film that would parade daily through the busiest streets in Taipei with a band performing the song, hastening its rapid spread.

The sensation caused by the song set a new standard for movie promotion, and numerous hits from then on were created in this manner. Singer Chun-chun also achieved fame as one of the first Taiwanese pop stars, whose stories will be covered in next week’s Taiwan in Time.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.