From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law.

To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum.

In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions under what they called a free and democratic state.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

In reality, what was banned often came down to the whims of those in charge: “The people could never predict when the great sword of censorship would drop, they could only keep guessing the thoughts of the authorities,” a display states.

“Teacher, why didn’t he get hit for speaking Cantonese?” reads a poem by Lim Chong-goan (林宗源) in the Mandarin policy exhibition. “Teacher, why wasn’t he fined for speaking English? The teacher then grabbed the bamboo stick and smashed my heart.”

FORBIDDEN TOMES

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

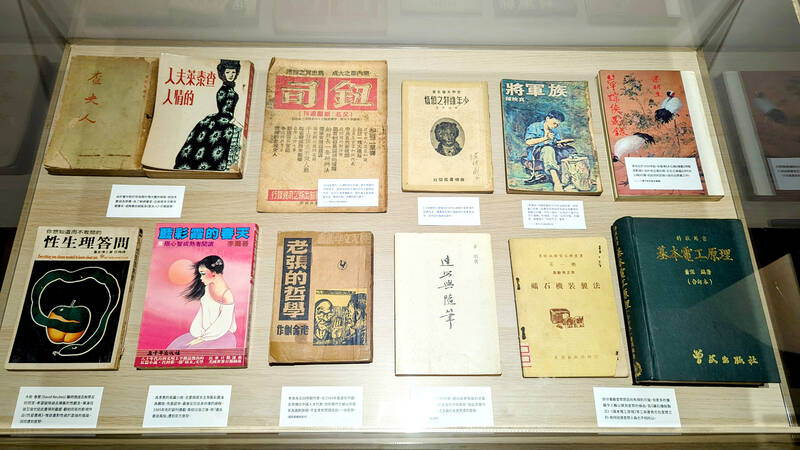

Even for someone like me who has done extensive research on censorship, the scope of the bans is still jarring. Leftist, erotic and anti-government titles are obvious, but martial arts novels, machinery textbooks — and the dictionary?

Opening last Friday, this new exhibition offers a comprehensive look at how the authorities suppressed publishing freedom and those who paid the price for reading banned material.

While the introductory text and section headers are translated into English, the rest of the display is entirely in Chinese. This has been a continued gripe of mine at this national-level institution. That being said, Google Translate’s Lens feature does an adequate job — it’s even able to translate some handwritten documents.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The first part lays out the legal basis for censorship as well as the influence a single Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) committee had over what was allowed to be published. Needless to say, any mention of the 228 Incident was taboo until the 1980s.

The Cultural Purity Movement in 1954 targeted people deemed “red” (leftist), “yellow” (sexual) and “black” (exposing government secrets), but the actual standards were much looser. Indeed, anything that the government didn’t agree with politically or deemed immoral and harmful to society could be banned — including a book on how to pick up women using English. The popular martial arts novels by Jin Yong (金庸) were also prohibited, presumably due to the characters’ defiance of authority.

Dictionaries and car manuals were struck down if the writer remained in China after the Chinese Civil War. Even the German novel The Sorrows of Young Werther was targeted because the translator was a leftist.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“Unless you lock people inside a small world and forbid them from any outside contact, these methods will not work,” wrote Free China magazine in 1956.

Taiwanese continued to be arrested for speaking out against the policy or reading illegal books, but publishers always found ways to circumvent the censors. Still, many writers remained silent, hiding their manuscripts or abandoning writing altogether.

It’s a solid, informative exhibit, one that could be made better if the museum expanded the small banned books library section into a regular feature and keep adding to the list.

Those who don’t read Chinese might want to give it a pass, though it’s worth a visit if seen in conjunction with the excellent permanent installation and other exhibits, including The Spectre of Freedom: Art of Resistance featuring the work of Hungarian artist Steven Balogh.

SILENCED TONGUES

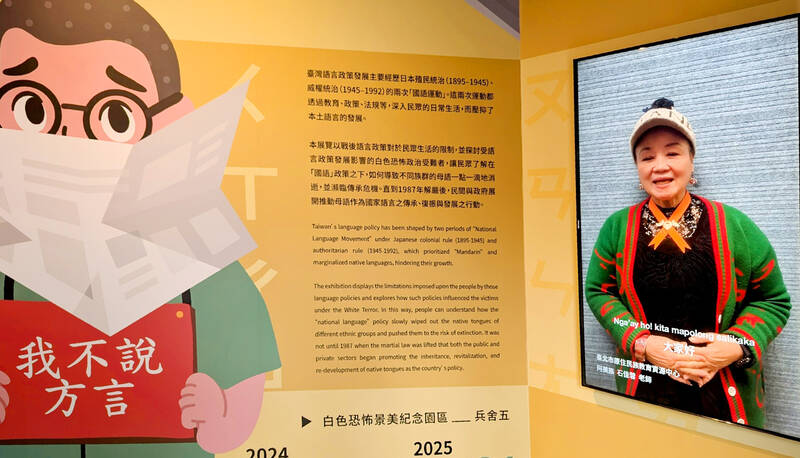

“Mandarin Monopoly?!”, on the other hand, is fully translated into English. Visitors are welcomed by a video screen of people speaking Paiwan, Atayal, Amis, Hakka and Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese), a reminder that the nation’s various languages persevered despite KMT censorship.

However, the damage to some of the nation’s other languages is irreversible. It’s one thing to reprint banned books, but it’s much harder to get people to start speaking their once-banned languages, especially indigenous languages, again.

The exhibition notes the Japanese also banned local languages and publishing in Chinese after 1937, rewarding families who primarily spoke Japanese at home. After the war, these families suddenly were barred from using Japanese, and were forced to learn Mandarin.

A selection of writings by political prisoners in this early period of KMT rule shows the struggle people had with this new language, including a written request by Huang Lung-sheng (黃龍勝) to have a Hakka-speaking judge translate during his trial, and a letter by White Terror victim Uyongu Yatauyungana detailing to his family how difficult it was to write in Chinese — he had to dictate it in Japanese to a fellow prisoner, who translated it into Chinese then transcribed it.

A significant part of this exhibition covers the punishments levied on those who broke the rules. Even speaking Mandarin with a Taiwanese accent was considered backwards and vulgar compared to regional Chinese accents spoken by immigrants fleeing the Chinese Civil War.

“After I grew up, I asked my parents why they didn’t teach me the language of our people,” writes indigenous Truku author Apyang Imiq. “Mother replied, why do you blame me? When I spoke our language at school I had to wear a sign around my neck. Father replied, why do you blame me? When I spoke our language in the army, I was slapped by the sergeant, who said I was speaking the devil’s tongue to confuse others.”

As with banned books, people still found ways to preserve their language, and in the 1980s activists began fighting to reclaim their endangered heritage. At the end of this excellent, well-thought out exhibition, visitors are encouraged to leave a message in their mother tongue for others to hear. I recorded mine in Cantonese.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.