It was only a matter of time before US President Donald Trump set his sights on Taiwan. Based on his congratulatory phone call to former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) after her return to power in 2020, the more optimistic among us might have hope for continued support.

Alas, Trump 2.0 is a proposition that has taken even the most canny and cynical of observers by surprise with the aggression he and his administration have shown toward traditional allies. Following threatened tariffs against Canada and Mexico and hints of the same against Europe, Trump raised the prospect of trade sanctions against Taiwan, which he accused of stealing US microprocessor know-how.

“Taiwan took our chip business away,” Trump told a press conference on Feb. 13. He followed this up with a threat of 100 percent duties on chips from Taiwan “if they don’t bring it back.”

To anyone who had been listening to his campaign pledges, it shouldn’t have been a bombshell. In July last year, Trump had told Bloomberg that Taiwan stole the US’ chip manufacturing industry, that Taipei gave America nothing and that, as such, it should pay Washington for defense just like “an insurance policy.”

Economists and industry experts quickly pointed to the impracticalities of Trump’s strategy, arguing that hitting Taiwan with exorbitant tariffs would simply drive high-end chip prices up, with US consumers footing the bill. The idea that this was would suddenly drive reshoring was also dismissed, with the five-year lead time on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC) first Arizona fab, set to open this year, offered as an example of how long these things take, and the obvious issues of labor costs highlighted.

Elsewhere, Trump’s critics charged that the president betrayed a fundamental misunderstanding of how the semiconductor industry works: The US, they explained, was largely responsible for chip design, while Taiwan focused on manufacturing. President William Lai (賴清德) echoed these remarks, calling the industry an “ecosystem” which relied on a division of labor.

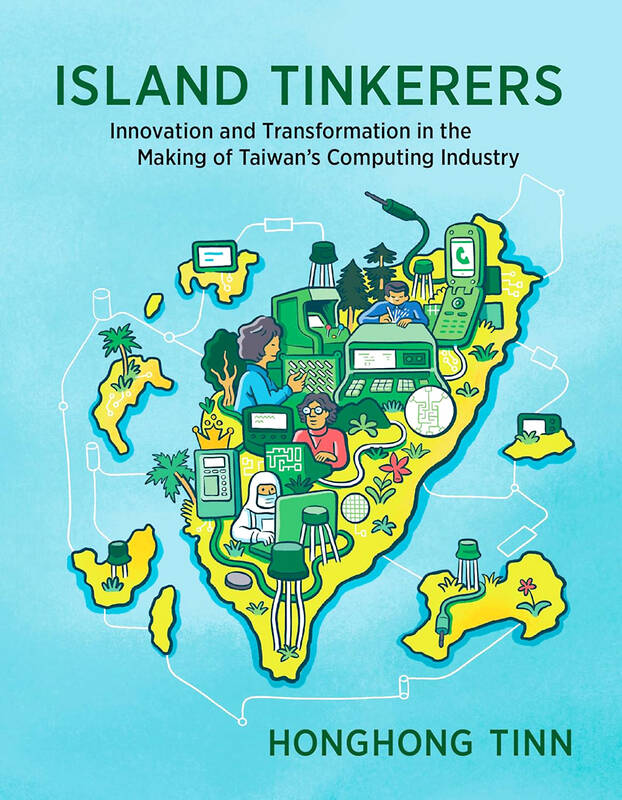

In response, Trump might argue that this was not always so. As Honghong Tinn (鄭芳芳) writes in this engrossing and meticulously researched new book, it wasn’t until 1987, when Morris Chang (張忠謀) founded TSMC as the world’s first dedicated or pure-play foundry, that these distinct roles emerged. Prior to that, leading US technology companies, such as Intel, IBM and Texas Instruments and Asian giants such as Samsung and Toshiba had been integrated device manufacturers, handling all aspects of chip design and fabrication.

REPLICATING SUCCESS

The dedicated foundry model, which Tinn notes may have been pilfered from then-UMC chairman Robert Tsao (曹興誠), who had previously consulted Chang about the feasibility of such an undertaking, was established after Taiwan’s “godfather of technology” minister without portfolio Li Kwo-ting (李國鼎) persuaded Chang to relocate to Taiwan to head the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI).

Unlike most of the technologists featured in this book, Chang had never previously lived in Taiwan but “had shaped Taiwan’s electronics industry in a substantive manner” as an informal advisor to the government on technology transfer projects, establishment of manufacturing facilities, and subcontracting work for Texas Instruments and, later, General Instrument.

Chang and Tsao’s hunch that dedicated foundries were the way forward for Taiwan was based on several considerations, including the belief that the tinkering-based know-how that had brought Taiwan’s researchers, engineers and technicians success in computer manufacturing could be replicated in the production of integrated circuits (ICs). Another prediction was that IC demand would soon explode, leading electronics companies that lacked the requisite expertise to outsource production.

In such an environment, large-scale manufacturers would thrive, Chang believed. He was also inspired by Introduction to VLSI System, a legendary textbook by a pair of American computer scientists that is credited with spawning the IC design industry and the division with manufacturing.

MISSING THE BOAT

More evidence that all of this started before America needed making great again, the Magadonians will insist. Perhaps. But, leaving aside the issues of legitimate technology transfer through official cooperation, the emergence of transnational supply chains, and the legions of US-educated Taiwanese- and Chinese-Americans who moved seamlessly between countries and institutions, a key point missed by those who cry theft is that the US big guns were invited in from the get-go, but declined.

In fact, on trips to the US to raise seed money, Chang failed to get a hearing with most companies who considered his proposal “unfeasible.” The two that did receive his pitch — Intel and Texas Instruments — politely declined. In the end, Dutch multinational Philips was the sole foreign investor with 27.5 percent of the startup capital.

True, Intel did soon send personnel to Taiwan to finesse TSMC’s processes with a view to eventually having them subcontract. This began with “leftover” contracts but, with Intel soon unable to fulfil orders, quickly became an official “qualified” independent contractor arrangement. By the mid-1990s, most of TSMC’s sales were to fabless design firms.

But all of this misses the point: Trump’s playbook on how to lose friends and alienate people tramples all over a relationship that was and continues to be founded on mutual benefit.

‘ASPIRATIONAL TINKERERS’

Tracing the history of Taiwanese tinkering to National Chiao Tung University (NCTU) alumni who pushed for the re-establishment of the institution in Taiwan, Tinn not only contradicts received wisdom about top-down processes, but she also shows how this was a transnational process from the start.

To be sure, officials played a role, with vice minister of communications Chien Chi-chen (錢其琛) pushing the bid for technical assistance under a United Nations Special Program — the kind of fruitful cooperation that Trump and his enforcer Elon Musk are currently attempting to end.

In her conclusion, Tinn uses the example of a US high school team comprising undocumented immigrants which bested a group of MIT grads in a robot design competition to highlight what “aspirational tinkerers” can achieve.

Chien and other early technologists cunningly secured government approval by tying the field of electrical engineering to atomic energy — an obsession of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣中正) and his Chinese Nationalist Party government.

There are, Tinn notes in her conclusion, clear parallels with the way Taiwan’s contemporary technologists have made their products indispensable — not only to their own national defense but to that of the US and, indeed, the world. Trump would do well to remember where some of the specialized chips used in American fighter jets are sourced.

Aside from pragmatic concerns, something more affecting, more essential permeates the pages of this remarkable story: the close personal bonds that were formed between generations of innovators that form the book’s dramatic personae.

Recalling fondly his time as training at an electronics factory in Watseka, Illinois, in the 1960s, Bruce C.H. Cheng (鄭崇華) — who would later found Delta Electronics — was struck by the camaraderie he was shown.

His American coworkers were aware that their company was poised to establish a Taiwan facility, jeopardizing their own livelihoods. Joking that they would be hastening their redundancy if Cheng learned too fast, they nevertheless took him under their wing.

“[They] remained enthusiastic about teaching Cheng and his fellow Taiwanese colleagues every part of the production,” writes Tinn, “and they generously took turns inviting Cheng and others to each of their homes.”

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name