June 2 to June 8

Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry.

Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey.

Photos: Liao Hsueh-ju, Taipei Times

Peng recounts some of his accidents in the book, Biographies of Professionals at the Jhudong Forestry Center (竹東林場職人傳). His most serious injury occurred when a tree he was logging fell on his head. He says his chin still hurts from this incident.

Logging came relatively late to the forests near Hsinchu’s Jhudong Township (竹東), beginning in the 1940s to provide wood to the Imperial Japanese Navy as World War II intensified. After the war, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) consolidated the operations in the area and established the Jhudong Forestry Center, which created a bustling timber industry in downtown Jhudong Township.

Increasing government restrictions on logging led to the industry’s demise in the 1980s, and the last tree on this site was cut in 1988. There’s been growing attention to preserving this heritage, and last week, the surviving structures related to the Jhudong Forestry Center, mostly located around Jhudong Railway Station, were collectively listed as historic buildings.

Photos: Liao Hsueh-ju, Taipei Times

TIMBER FOR WAR

The Japanese colonial government began harvesting Taiwan’s abundant timber resources early into their rule, establishing the three state-run logging centers of Alishan (阿里山), Baxianshan (八仙山) and Tapingshan (太平山). They also encouraged and supported private businesses to partake in the industry.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

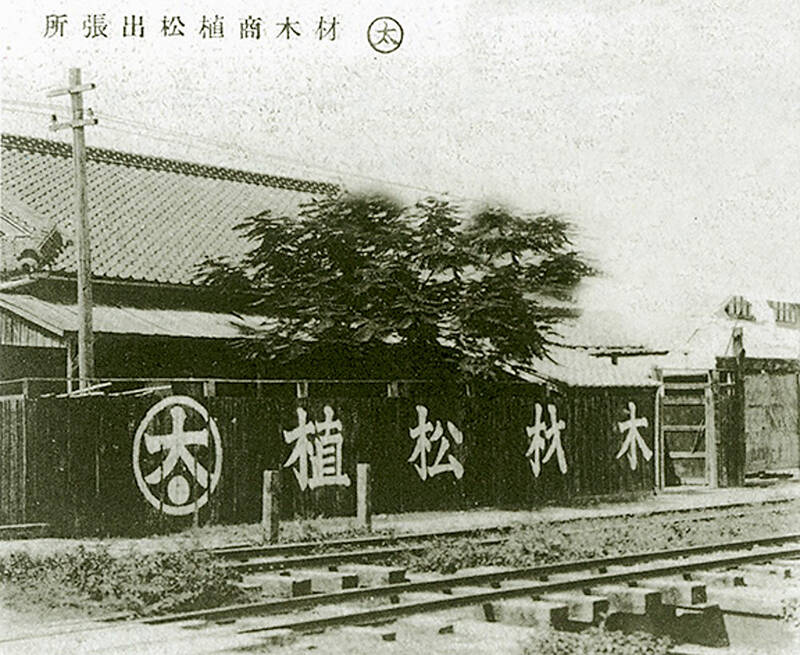

One of the major players was Uematsu Timber Enterprise, established in 1906 by Kichizou Hirato. Based in Taipei, the company first imported Japanese wood to Taiwan for various public works, later expanding to the timber centers of Chiayi, Fengyuan and Luodong.

In 1940, Uematsu set up operations in Jhudong and began harvesting Taiwanese China fir in Xiangshan Mountain (香杉山), about 36km from the town, writes Han Shang-ju (韓尚儒) in “The development of Jhudong and its forest industry” (竹東發展與林業變遷). The total logging area was 1,483 hectares.

All of the timber was to go to the Imperial Japanese Navy as material for their warships, and high-ranking military officers often visited the timber factory in town for inspection. Compared to the more commonly harvested red and yellow cypress, Han writes, the military preferred Taiwanese China fir as it was highly resistant to water, corrosion and termites. The wood was often used for the ship’s keel.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

In 1943, a second company entered Jhudong: The Taiwan Development Co, which was established in 1936 to develop and procure resources to support Japan’s southbound ambitions. Before arriving in Jhudong, it had already conducted large-scale logging across Taiwan as wartime demand for timber soared.

It targeted a large area designated as Luchang Mountain (鹿場山) that spanned Hsinchu and Miaoli counties, but due to a lack of resources during wartime, progress was slow and it did not start producing timber until December 1945, after the Japanese had already lost the war.

Photo courtesy of Hakka Cloud

THE TOWN PROSPERS

The Japanese had severely depleted Taiwan’s forests during World War II, as the total logging area increased from 18,422 hectares in 1936 to 40,894 hectares in 1942. Upon their arrival in 1945, the KMT at first planned to ban logging for five years — but due to the demand for timber and revenue, they quickly reversed course, but with tighter restrictions and a focus on restoring the forests at the same time.

The Forestry Administration Division combined the timber forests from both Japanese companies into the Jhudong Forestry Center on Aug. 16, 1947. It was one of six forestry centers in Taiwan, the others were Baxianshan, Taipingshan, Taroko (太魯閣), Luandashan (巒大山) and Alishan.

The forestry officials took over the Japanese-era facilities in Jhudong and expanded the operations, and all the timber from these mountains were transported to town to be processed and shipped off. During the 1950s, Jhudong became a vibrant, prosperous center for timber.

One elder recalls in a Hsinchu Archives (新竹文獻) article: “The fragrance of timber is apparent once you exit the railway station. You could hear loggers shouting, and factories are everywhere, with timber piling up like mountains. Within a 3km radius of the railway station, it’s an entire world of timber.”

At the same time, Jhudong Forestry Center also doubled as a headquarters for secret agents during the White Terror era, and the Jhudong Township Annals (竹東鎮誌) states that general manager Yen Fu-hua (顏福華) was actually the head of the operation. There’s been calls for it to receive “site of injustice” status in addition to the historic designation.

CHANGING TIMES

Peng, who began working in the logging industry at the age of 16, arrived at Jhudong during the roaring 50s. He lived in Neiwan, and he would carry all his equipment, including axes and a large saw, on a shoulder pole and walk barefoot to the bus stop bound for Jhudong. Once he arrived, there was still the backbreaking journey to the forests via cable car or manual trolley.

Everything was done manually, from cutting the tree to collecting and packing the wood to transporting it to town, and each step was perilous as the massive logs could easily crush workers.

Things changed with the establishment of the Forestry Bureau in 1960. In 1964, the McCulloch chainsaw was introduced, as well as diesel and gasoline harvesters. The bureau also opened up forestry roads so that trucks could transport the lumber to town.

As Taiwan’s economy shifted to heavy industry in the 1970s, the importance of the forestry and agriculture sectors decreased. Awareness of forest conservation also grew during this time.

In 1976, the government unveiled the Taiwan Forestry Management Reform Plan, which greatly limited logging and promoted reforestation and soil and water conservation. The restrictions tightened as time went on, and in 1985, the government completely banned logging of natural woodland, all but bringing an end to the timber industry.

Jhudong still saw sporadic activity after this, but by 1989, all logging had ceased.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name