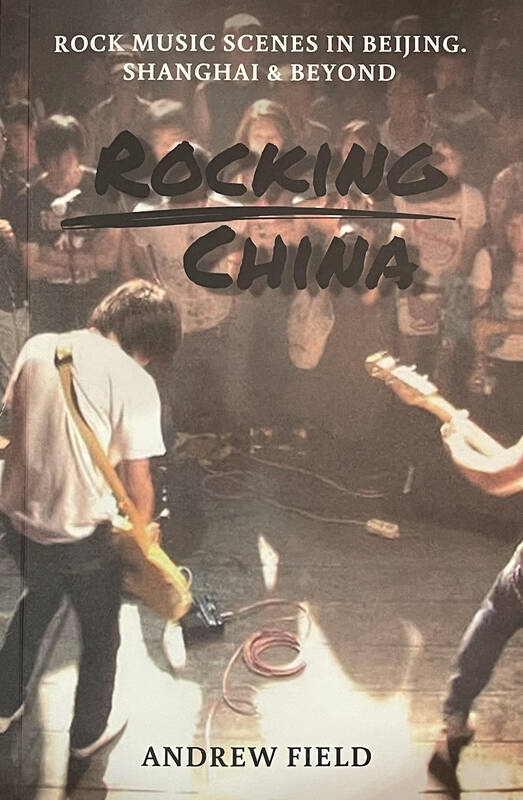

In a recent book, Rocking China, Andrew Field, a professor of Chinese culture and history at Duke Kunshan University in Suzhou, looks back at Beijing’s independent rock scene circa 2007, arguing that the year marked both its apex and curtain call. Until that point, the scene’s growth had come at a breakneck pace. China had seen the birth of Chinese rock ‘n’ roll just 21 years previously in 1986 and its first ever punk rock gig just 12 years before in 1995. Then somehow, by the mid-2000s, Beijing had spawned a full fledged indie music industry. New clubs were buzzing with new bands who were getting signed to new labels and performing on massive stages at new music festivals. It was a heady time, but it wasn’t destined to last.

Freedom of expression in China has always swung like a yo-yo at the Chinese Communist Party’s whims, and just one year after this 2007 pinnacle came the lead up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics. China’s government clamped down hard on non-official events and voices, especially in Beijing. Clubs were raided, festivals were shut down, and foreign artists were refused permission to perform. In the years that followed, especially since Chinese leader Xi Jinping (習近平) came to power as China’s president in 2012, the python of Chinese officialdom, already coiled, continued to squeeze. By 2022 only one rock club, School Bar, remained in Beijing, according to Field.

I can corroborate some of this from my own experience reporting on China’s indie scene between 2006 and 2008.

I remember the bizarre spectacle of the 2006 Beijing Pop Festival, whose very name camouflaged the fact that it was an indie music event. Event founder Jason Magnus, an American that Field alleges gained powerful connections through his engagement to former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s (鄧小平) granddaughter, kept empty a large area in front of the stage that at other festivals would hold the pit of hardcore fans. Technically this was the VIP area, and it was cordoned off by metal barricades and a line of security staff in military-type uniforms –– 1,000 security personnel for 10,000 attendees, according to one report. The real rock fans were kept far from the stage.

Just a year later, in 2007, that same festival hosted the New York Dolls, Public Enemy, Nine Inch Nails and Marky Ramone. The Yeah, Yeah, Yeahs played at another Beijing event that same year, the inaugural Modern Sky Festival, organized by the Modern Sky record label, which would go on to commercialize Chinese indie and is today a major label.

But then in March 2008 at a concert in Shanghai, Icelanding pop singer Bjork chanted “Tibet, Tibet” during her song Declare Independence. This subtle reference drew international scrutiny to Beijing’s obliteration of Tibetan culture and identity just as the Olympic torch relay was about to begin.

In that Olympic year, the Beijing Pop Festival was cancelled, and alternative spaces all over China were squeezed. Even in distant Shenzhen, government pressure led to closures of at least two dozen music venues and alternative spaces, including a hipster cafe run by a friend of mine. At the same time, Beijing’s major rock festivals relocated to outer provinces.

GOLDEN YEARS

Field’s book does not dwell at length on this decline but instead aims to present a document of the golden years of Beijing rock leading up to 2007. He takes a close look at China’s then newly matured cohort of punk and post-punk indie bands –– SUBS, PK14, Hedgehog, Carsick Cars, Joyside, Re-TROS, Hang on the Box, Brain Failure, Lonely China Day, and Guai Li –– and also the seminal clubs where they played such as D-22, 2 Kolegas, Yugong Yishan and Mao Live House.

Though Field does not make a big point of it, foreigners played an enormous role in constructing this underground framework. Michael Pettis, an American financial trader and economist who has taught at Peking University since 2002, not only opened and funded the scene’s most important club in D-22 –– it ran from 2006 to 2012, often at a loss. In 2007, Pettis also hired PK14 vocalist Yang Haisong (楊海崧) to head up what some would call China’s third indie music label of consequence, Maybe Mars. (China’s first two indie labels were Scream Records, an offshoot of a Beijing punk club, and Modern Sky.) By 2015, Maybe Mars had released more than 60 albums by Chinese indie bands.

Through figures like Pettis and Matt Kagler, an American who founded Tag Team Records in Beijing in 2005, Chinese indie was suddenly able to bridge the gap to the outside world. Bands like Lonely China Day and Carsick Cars were getting reviewed by topflight critics in the New Yorker and New York Times. Carsick Cars was able to tour Europe opening for Sonic Youth and release records in Australia and the UK. Brain Failure performed at the Japanese music festival Fuji Rock, while other groups traveled to the SXSW festival in the US.

Japanese influence was also prominent. Beijing’s biggest and most professional club, Mao Live House, was a joint venture with Japan’s Bad News Records. (I remember getting a tour by the club’s Japanese manager, an experimental 8-bit musician named Sam2, whom I’d first met at the Taiwanese music festival Spring Scream.)

‘REBELS WITH A CAUSE’

But the voices coming across on these albums and club stages were those of China’s youth. Field argues that the bands were indeed “rebels with a cause.” Through interviews, he reveals that their revolution did not fit the anti-government narratives that western media hoped to pin on them. Instead of directly criticizing China’s government, which could land them in jail, China’s rockers creatively explored other spaces of resistance. They opposed paternalism, conservative values, and social conformity.

SUBS vocalist Kang Mao (抗貓) said she wrote the song Down after her father criticized her for having “no money, no job, no family and no future.”

“I embedded in the lyrics this notion that although I have nothing, I’m happily going downward,” she said.

PK14 frontman Yang Haisong meanwhile declared that rock music showed him “there’s another life you can live.” He described his music as resonating with Chinese youth –– especially those in second or third tier cities –– who “have a passion, but the passion has just no direction….They want to do something, but they don’t know why they should do this.”

Chinese indie music had by 2007 become an urgent expression of youthful ideas, much as everywhere else.

DECIMATED SCENE

Today, many of the bands Field documents in Rocking China continue to perform and as senior indie acts in China’s scene. But the scene has shifted, in many ways for the worse. Since 2008, Beijing’s indie scene has flagged not only because Xi Jinping has smothered the capital’s alternative spaces, but also because labels like Modern Sky forged a path to commercializing indie music, streaming replaced physical music and electronic dance clubs, which are essentially apolitical, offer greater mainstream appeal. As of 2021, Field even goes so far as to argue that Beijing’s band scene has been so badly decimated that it’s been surpassed by Shanghai’s scene, which has always been known for its anemic underground. Small scenes have also appeared in other major cities.

Field’s view is however fairly narrow, relying on small windows of information gathering and his personal relocation from Beijing to Shanghai in 2008. In Rocking China, he also gives us a very frustrating read, an awkward mix of academic field notes and minimally edited journaling. Interviews often present cliches as revelations –– like when one Chinese rocker declares, “Rock music came to China from the West… but now it’s starting to take on Chinese characteristics.”

Also, when Field refers to “gigs” as “concerts,” to “heavy metal” as “metal rock” and gig attendance as “site visits,” we can tell he is in alien territory and not sure what audience he is writing for.

Also regrettable, Field’s book is soft in terms of context and organization, an indulgence I could not afford for this review. For something much better, I’d recommend the recent Punk in China” podcast series by Maybe Mars’ former operations manager Nevin Domer, available online as part of Equalizing Distort Radio on Toronto’s CUIT radio. Domer’s ongoing chronicle of China’s scene is truly excellent.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and