A dozen excited 10-year-olds are bouncing in their chairs. The small classroom’s walls are lined with racks of wetsuits and water equipment, and decorated with posters of turtles. But the students’ eyes are trained on their teacher, Tseng Ching-ming, describing the currents and sea conditions at nearby Banana Bay, where they’ll soon be going.

“Today you have one mission: to take off your equipment and float in the water,” he says.

Some of the kids grin, nervously. They don’t know it, but the students from Kenting-Eluan elementary school on Taiwan’s southernmost point, are rare among their peers and predecessors.

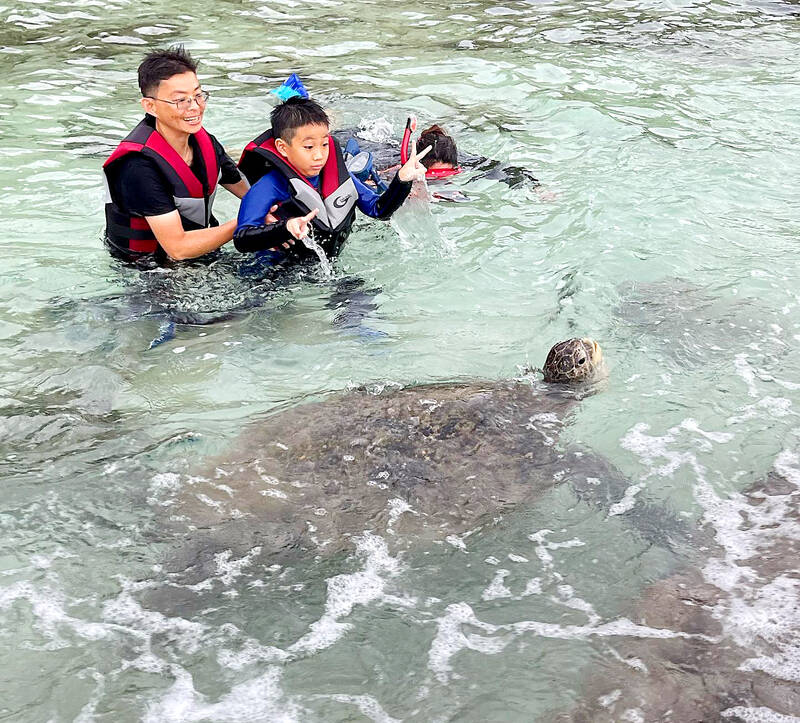

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsien, Taipei Times

Despite most of Taiwan’s 24 million residents living near the coast and rivers, swimming ability is low. Ocean safety skills are even lower. Classes like Tseng’s rely on a few passionate individuals who want to share their love of the sea.

They’re up against a lot — entrenched parental protectiveness, bureaucratic risk aversion, the legacy of decades of militarized coastlines, even ghosts.

For the past decade or two there has been a concerted push to shift the swimming culture, and address high drowning rates and the missed opportunities for fun. It’s been mostly driven by dedicated teachers and public servants, families resisting social pressure and one “really crazy” president.

Photo: Lee Hui-chou, Taipei Times

Tseng’s class finishes quickly and everyone piles into cars with a few adult helpers. At Banana Bay the children pick their way through jagged volcanic rock before launching themselves into the small but choppy waves.

“We don’t want to be in the classroom, we want to be in the water the whole time, everyday,” one young girl says.

DANGER

Photo: Chen Yen-ting, Taipei Times

A 2010 Ocean University survey found just 44 percent of Taiwanese say they can swim. This compares with more than half of Hongkongers, around 66 percent of UK nationals, and 75 percent of Australians — a rate near the global average of 76 percent for high-income countries, of which Taiwan is one.

Like Australia, Taiwan can be stiflingly hot and has treacherous waterways and beaches. In Australian coastal communities, that means learning how to be safe in the ocean is considered crucial. In Taiwan, the response appeared to be more that the ocean is dangerous and so must be avoided.

The attitude manifests in ways from frustrating restrictions at beaches to tragically higher risks of drowning when swimming. In 2007, the rate of death by drowning for Taiwanese under-14s was reportedly three times higher than for Australians.

The most common explanation for why swimming isn’t a big thing in Taiwan is that most parents are simply afraid of letting their children near the water.

Tseng laughs as he recalls his first class: skeptical parents lined up on the shore, arms folded and unblinking eyes trained firmly on their child.

“There are fewer kids in Taiwan so the kids are like treasures, and people don’t want accidents,” Tseng says, referring to Taiwan’s record low birth rates.

It’s a similar story on Siaoliouciou (小琉球), a small island off the coast of Kaohsiung, where an elementary school also offers an ocean skills curriculum and is among those now famous for underwater graduation ceremonies.

“If the school doesn’t teach this, the kids have to rely on their family for the water education,” teacher Hong Zi-lun says.

But that’s unlikely.

“These families grew up near the beach but actually are afraid of water and their parents don’t want them to swim.”

Risk aversion also appears to be institutional. Strict rules abound and beaches close frequently. Lifeguards have been known to tell people to get out of knee-deep water or — in the case of one holidaying Australian couple — seeking signed pledges they wouldn’t ask for rescue in return for being allowed in. Cheng Shih-Chung, director-general of Taiwan’s Sports Administration, says they likely fear they’ll be held liable if someone drowns. So it’s easier just to keep people out of the water.

Downhill from the school, two Taipei women in their 40s shriek as waves crash around their feet at Secret Beach. The misnamed cove is a popular snorkeling spot.

“This beach is beautiful, I love it,” Winnie Kuo says. But she can’t go in. Instead they’re waiting for her 19-year-old daughter to arrive.

“When we were young our parents didn’t let us go to the beach, so we never had the opportunity to learn to swim,” Kuo laments.

Part of the reason millennials like Kuo weren’t taught is that their parents grew up under martial law, which ended in the mid 1980s. Back then, civilians were largely kept away from natural swimming places, militarized coastlines were patrolled for invaders or escapees, and some riversides were execution grounds. An elderly Keelung man vividly remembers bodies floating in the harbor after a government crackdown in 1947.

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS

Such incidents, as well as the hundreds of drowning deaths each year, also feed into religious beliefs about the water.

“People are very superstitious and individual families’ gods will sometimes appear in dreams and tell parents that their kid will have trouble with water,” says Hong about the deeply traditional island of Siaoliuciou.

More than 76 percent of people in Taiwan practice a folk religion, Buddhism, Taoism, or a blend of the above, and most involve beliefs about the danger of water. Taiwan’s midsummer — when drownings peak — also coincides with Ghost Month, a festival to honor ancestors and ghosts with no descendants.

“People believe there are some ghosts in the water that will pull you in so you can replace them and they can go to another life,” says Cheng.

At a secluded, unpatrolled stretch of river outside Taipei, a small swimming-loving community holds a Ghost Month ceremony each year. The locals swim almost daily, but they still make sure to honor the spirits of people who drowned here, and ask them not to take anyone else.

Successive governments have attempted to improve drowning rates but the most ambitious attempt was launched by former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) in 2011.

The 12-year plan sought to get 80 percent of students swimming, and raise rates among public servants and first responders. At the time, there was no requirement that even coast guard personnel be able to swim — Ma’s plan called for 100 percent. It set targets of 80 percent of police, 90 percent of firefighters, and 85 percent of military personnel. Taiwan was a maritime country, Ma said at the time. It would be “a bit embarrassing” if they didn’t.

The government built hundreds of pools, mandated swimming lessons in schools, and embedded skill tests into public service recruitment.

“It required someone who was really crazy about swimming,” Ma tells the Guardian. “Taiwan is an island surrounded by sea … and [parents] should be assured that the kids have learned swimming and swim well.”

Ma’s love of swimming was sparked by a lucky escape as a teenager.

“I was just playing a little bit but suddenly I found that my feet couldn’t reach the bottom,” he recalls, sitting back in his Taipei office. “I didn’t panic, I just sank myself to the bottom then jumped up and shouted ‘help.’ The lifeguard came in about 15 seconds and I was pulled out. But it was a shock, so I started to learn to swim.”

Now 74, and nearly a decade out of government, Ma still swims a kilometer several times a week in a pool operated by the secret service. For him, swimming is the answer to almost anything.

“Xi Jinping (習近平) also likes to swim,” Ma says, unprompted, in an interview granted on the understanding we wouldn’t talk about China. Ma has met Xi — the Chinese leader planning to annex Taiwan — on several occasions during which, he tells us, they also talked about swimming.

“One day maybe we could meet and swim together,” he muses, prompting a nearby advisor to sit up in his chair.

“I’d hope I could beat him. So if I beat him, I’d say: you swear that you won’t invade Taiwan.”

Ma chuckles. He is joking, his minders are very quick to clarify. We take it as a sign of just how much Ma likes swimming.

‘MOST PARENTS STILL AFRAID’

There are no available statistics to show progress since the 2010 survey. Anecdotally there are improvements, but more than 50 percent of schools in some counties reportedly still don’t offer the mandatory lessons, which Cheng blames on a lack of facilities outside cities.

One former Taipei city firefighter, Eddie Lin, and says Ma “meant well” with his swimming dream for Taiwan, but he doesn’t think it’s panned out.

“Most parents are still afraid.”

Cheng says water sports are growing in popularity, but he can’t picture a future where Taiwan’s people are confident at the beach. Fear is just too deeply entrenched, and the national lessons are still basic and “not yet for the rivers, lakes and oceans”.

The independent school programs do however offer hope. Tseng’s classes are now so popular that some families moved towns so their kids can attend. Local parents still don’t often take their kids swimming separately, but at least none of them are showing up to supervise the class any more. Most importantly, the students love it.

“If you learn the risks you can make swimming a really safe sport,” says Andy Tseng, a freediver assisting teacher Tseng Ching-ming. “We teach students that the ocean is not something to be afraid of.”

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a