The Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) five-decade authoritarian rule of Taiwan was so rife with injustice that it’s hard to capture how bad things could get. Several works get close: George H. Kerr’s Formosa Betrayed and Elegy of Sweet Potatoes by Tehpen Tsai (蔡德本), for example.

More recently, Facing the Calamity by Fred Him-San Chin (陳欽生), who was brutally tortured into a false confession and then imprisoned for 12 years, has exposed the relentless grind of a KMT state security apparatus, which crushed up and spit out individuals who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time (and many who weren’t.) Anyone seeking to understand the kinds of things that could happen once someone was caught in the jaws of the machine should visit Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park (白色恐怖景美紀念園區), where Chin offers tours based on his experience in the former prison grounds where he was held.

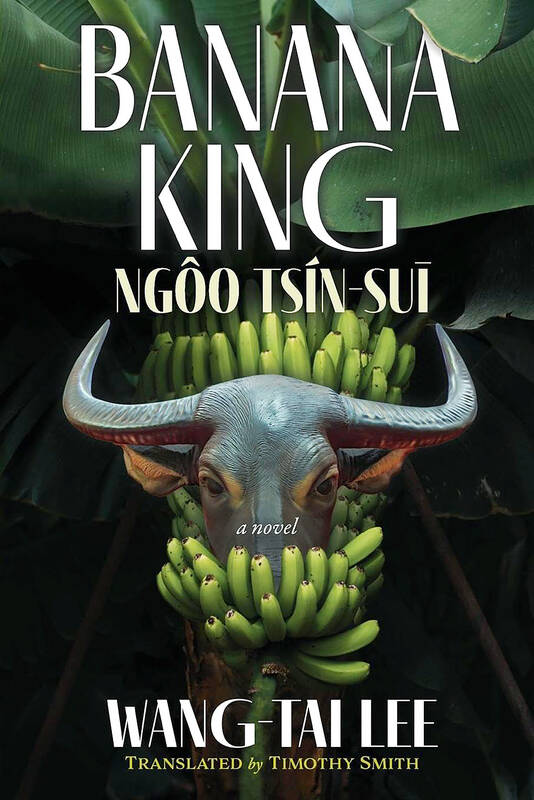

This fictionalized but, in its fundamentals, strongly fact-based account of a long-forgotten figure from postwar Taiwan’s fruit industry is worthy of shelf space alongside such works.

BANANA MAGGOT

The story of Ngoo Tsin-sui’s metamorphosis from “Banana King” to “Banana Maggot,” stage-managed by senior officials who met defiance of their orders and the associated loss of face with merciless retribution, is shocking and deeply moving.

In an afterword, translator Timothy Smith notes that working on the book “made my blood boil at certain parts and left me in a depressed stupor at others.” Foremost among the distressing images is that of Iap Tshiu-bok (葉秋木), a Pingtung city councilor and childhood friend of Ngoo’s who is horrifically mutilated before being loaded on the back of a truck and executed in a public square during the 228 crackdown. Should any reader feel the scene is overdone, the original Chinese actually toned down the historical details, Smith reveals.

The incident sparks a psychosomatic response in Ngoo, sending streaks of pain pulsating down his spine and throughout his body — a phenomenon that continues throughout his life whenever he is faces some new trauma (invariably brought about by another injustice.) And while Ngoo might not have suffered extreme physical mistreatment, following his incarceration, he notes that the mental and emotional toll were “much more horrendous…”

GOLDEN BOWL BRIBES

The narrative follows Ngoo, known in Mandarin as Wu Chen-jui (吳振瑞), from humble beginnings as a headstrong teen ejected from his family home in rural Pingtung County, through his experience as a technician in a Japanese banana research station, and ultimately to the chairmanship of the Kaohsiung Green Fruits Export Association.

Along the way, he shows intelligence, charisma and a magical way with his beloved water buffalo, who symbolize the burden and resilience of the Taiwanese. The naive obstinacy that enraged his father is another facet of his personality and one that frequently leads him to the brink of disaster. While his colleagues, friends and family — and even those who, like the sneaky Garrison Command informant Ouyang, conspire in his undoing — admire his integrity, they often urge restraint.

Among those who believe the KMT regime is a chronic disease to be endured is Ngoo’s best friend Tong Tsuan-tsong, son of a steel magnate who has long advocated currying favor with party top brass. Having already been shaken down for a fortune, Tong Tsuang-tsong’s father Tong Ing (唐榮) invites then-vice president and premier Chen Cheng (陳誠) to the inauguration of his factory’s expanded premises.

As one sardonic bystander at the ceremony observes, Tong Senior is content to “hold Chen Cheng’s family jewels for him,” while Tong Junior bears the grimace of a man who is doing so with reluctance and disgust. Yet, with a heavy heart, he eventually follows his father’s advice, urging Ngoo to do the same. Even then, Tong Tsuan-tsong sees his business confiscated for alleged financial malpractice. Where others see the futility of resistance, Ngoo is an optimist with faith in the basic reason and decency of humanity. Alas, he is frequently disappointed on both counts. Yet at times Ngoo tries to confirm, ingratiating himself with the appropriate bigwigs, only to back the wrong horse. In this regard, the power struggle between “the prince” Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), and “the empress” Soong Mei-ling (宋美齡), looms large as a backdrop to the novel’s events.

When things do go wrong, it is implied that it is then-minister of economic affairs Li Kwoh-ting (李國鼎) that pulls the rug out from under Ngoo’s feet. Having incurred Li’s wrath for ignoring his demand to sign up to an “unequal treaty” with a US firm, Ngoo is arrested and forced to confess to trumped up charges stemming from “awards” of golden bowls to officials in recognition of their “service” to banana farmers.

The irony of these “donations” — exorbitant bribes paid to various KMT front organizations — being later used to condemn the extorted parties, is obvious. In this way, the regime cultivated political patronage and kept big business on a leash. Individuals such as Li, who had an unblemished reputation in the West as Taiwan’s “godfather of technology,” may not have been on the take, but would not hesitate to destroy anyone undermining the bedrock of the system. Both the “Golden Bowl Incident” and the Tong Ing debacle were the subject of previous works of non-fiction, upon which author Lee Wang-tai (李旺台) relied for key details in this novel. The miscarriage of justice against Ngoo was revealed in the 2016 Chinese-language work The Banana Man: Wu Chen-jui and the Golden Bowl Case (金蕉傳奇:香蕉大王吳振瑞與金碗案的故事) by historian Huang Hsu-chu (黃旭初), which was published by the Pingtung County Government.

POLITICAL PROSE

While it’s always hard to judge prose in translation, there are some lovely touches in this novel from Lee, a former journalist. The passages dealing with Ngoo’s interactions with buffalo contain some of his finest writing. One example is an allegorical conversation between Ngoo and his father over the dangers of gambling. For the revelation that horse racing was a popular sport during the colonial era alone, the exchange is notable. But the discussion of the differences between buffalo and horses catches the attention.

“Buffalo can recognize themselves, recognize life, take things in their stride. All their movements are slow and deliberate, but they have patience and strength,” says Ngoo. While horses are also powerful, they manifest this through speed, Ngoo notes.

Interrupting, Ngoo’s father points out: “Horse[s] aren’t animals that we Taiwanese originally had…”

Praise is also due for Smith’s endeavors on the translation. A long-time resident of Taiwan, who is proficient in both Mandarin and Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), Smith had to work with Lee’s use of sometimes nonstandard Taigi Hanji — the rendering of Taiwanese through Chinese characters. Ditto the more sparing uses of Chinese characters to convey Hakka speech.

The conveyance of Taiwanese and Japanese idioms, culturally specific terminology and even onomatopoeic exclamations — the ubiquitous, disapprobatory honnh — is deftly achieved through a combination of repetition, extensive notes and — most impressively — context. There is the odd inconsistency with romanization and a couple of eye-catching errors — former President Yen Chia-kan (嚴家淦), who was premier when the Golden Bowl scandal broke, is referred to as Yen Chia-chin a couple of times. None of this detracts from the power of novel that captures the spirit of Taiwan and Taiwanese of all strata during a key transition in the country’s contemporary history.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South