When Angelica Oung received the notification that her Xiaohongshu account had been blocked for violating the social media app’s code of conduct, her mind started racing.

The only picture she had posted on her account, apart from her profile headshot, was of herself wearing an inflatable polar bear suit, holding a sign saying: “I love nuclear.” What could be the problem with that, wondered Oung, a clean energy activist in Taiwan.

Was it because, at a glance, her picture looked like someone holding a placard at a protest? Was it because her costume looked a bit like the white hazmat suits worn by China’s Covid prevention workers during the pandemic, who became a widely reviled symbol of the lockdown? Or was it because in the background was Taipei 101, Taiwan’s iconic skyscraper?

Photo: AFP

Oung never found out.

“It is really opaque,” she said, “my theory is that Xiaohongshu just got slammed with so many new accounts.”

TIKTOK REFUGEES

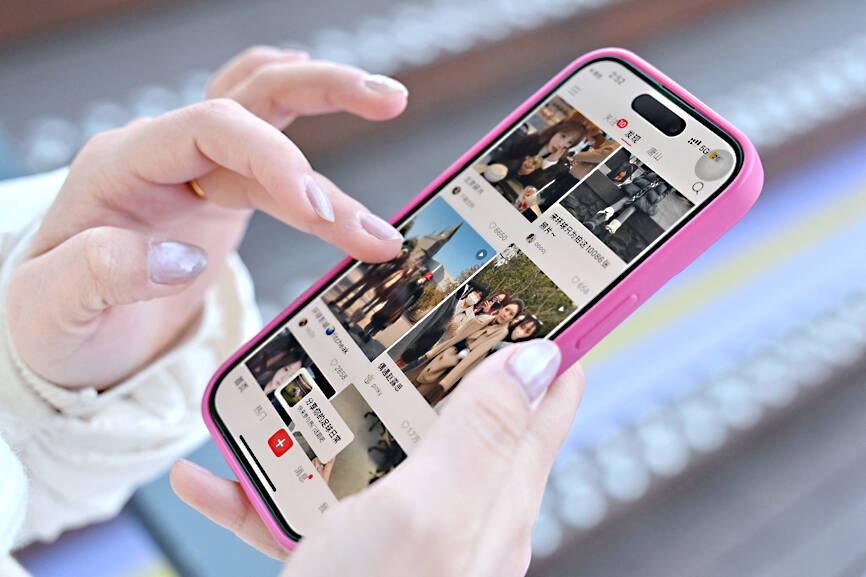

Photo: Reuters

More than 3 million US users signed up to Xiaohongshu last week, according to Reuters. “TikTok refugees” have fled to the app, also known as RedNote, as TikTok was banned in the US on Sunday after refusing to divest from its Chinese parent company, ByteDance.

On Friday, the US Supreme Court upheld the ruling, rejecting an appeal against the ban from TikTok, which has more than 170 million American users.

Founded in 2013 as an online community focused on shopping and travel tips, the Shanghai-based Xiaohongshu has more than 300 million, predominantly female, users. It is reportedly valued at US$17 billion.

The surge of new users it is experiencing has forced Xiaohongshu’s moderators to scramble to keep the content on the platform in line with Beijing’s censorship requirements. Unlike TikTok, which is an international subsidiary and has a sister app for Chinese users, Xiaohongshu is a purely Chinese operation.

TikTok’s detractors argue that it is a danger to national security because the users’ data is at risk of being compromised by China. Some lawmakers have also raised concerns that the content on the platform is manipulated to suit Beijing’s interests.

TikTok denies both of those accusations.

But fearful of losing access to their favorite app — and perhaps just jumping on a new trend — users have defied the lawmakers’ concerns about the Chinese Communist party and flocked to another Chinese platform.

WATCHFUL EYE

Like all Chinese social media, Xiaohongshu’s content is strictly censored in line with Beijing’s laws, which prohibit content deemed counter to the government’s interests.

In 2022, a leaked internal document revealed how Xiaohongshu censored “sudden incidents” on its platform, such as discussion of natural disasters and political disturbances.

But its existing guidelines are for Chinese-language content. This week, the hashtag “Red Note is urgently recruiting English content moderators” trended on Weibo, and job listings for English-language Xiaohongshu moderators have been appearing on recruitment websites. Chinese officials have reportedly told the company to ensure that China-based users can’t see posts from US users.

While Chinese internet users are adept at finding their ways round censorship, they are also used to self-censorship, avoiding certain topics that could get them blocked. On Xiaohongshu, they have tips for the American newcomers.

“DON’T mention sensitive topics,” counseled a lifestyle influencer.

“Don’t talk about religion or politics,” said a British user in China, who said he has been on the platform for five years.

Christine Lu, an entrepreneur based in Los Angeles, was also blocked from Xiaohongshu last week. As a test of the app’s censors, she had posted pictures that featured the Tibetan flag and the Taiwan flag — both topics that are considered “sensitive” in China.

“As suspected, it’s going to be impossible to have fully self-expressed conversations with Chinese people in China via this app,” Lu said on X.

Eric Liu, a former content moderator for Weibo, said: “It is still very difficult for Chinese internet companies to conduct English censorship … censors mainly rely on the understanding of China’s political correctness that is cultivated in school and in ideological and political courses … you can’t just rely on translation software.”

Liu said Xiaohongshu’s lack of English-language capacity meant that censorship was likely to be “rough and indiscriminate … giving priority to satisfying the requirements of the authorities.”

The censorship, and banning of users, may pour cold water on the idea that the app could be a place for Chinese and US internet users to communicate and share jokes and memes.

“I do think it is an unalloyed good that people who are in countries that are geopolitically at odds, and perhaps for good reason, just get to connect with each other,” said Oung.

But there will be a “rude awakening eventually.”

Oung says: “It’s a really interesting test of whether the Chinese government feels confident enough to actually let it continue.”

Chenchen Zhang, an assistant professor at Durham University, said that the current enthusiasm for the uniting power of social media is a “surreal” throwback to the utopian ideals of the internet in the 1990s.

The Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) told legislators last week that because the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) are continuing to block next year’s budget from passing, the nation could lose 1.5 percent of its GDP growth next year. According to the DGBAS report, officials presented to the legislature, the 2026 budget proposal includes NT$299.2 billion in funding for new projects and funding increases for various government functions. This funding only becomes available when the legislature approves it. The DGBAS estimates that every NT$10 billion in government money not spent shaves 0.05 percent off

Dec. 29 to Jan. 4 Like the Taoist Baode Temple (保德宮) featured in last week’s column, there’s little at first glance to suggest that Taipei’s Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會) has Indigenous roots. One hint is a small sign on the facade reading “Ketagalan Presbyterian Mission Association” — Ketagalan being an collective term for the Pingpu (plains Indigenous) groups who once inhabited much of northern Taiwan. Inside, a display on the back wall introduces the congregation’s founder Pan Shui-tu (潘水土), a member of the Pingpu settlement of Kipatauw, and provides information about the Ketagalan and their early involvement with Christianity. Most

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the

Like many retirement communities, The Terraces serves as a tranquil refuge for a nucleus of older people who no longer can travel to faraway places or engage in bold adventures. But they can still be thrust back to their days of wanderlust and thrill-seeking whenever caretakers at the community in Los Gatos, California, schedule a date for residents — many of whom are in their 80s and 90s — to take turns donning virtual reality headsets. Within a matter of minutes, the headsets can transport them to Europe, immerse them in the ocean depths or send them soaring on breathtaking hang-gliding expeditions