Supplements are no cottage industry. Hawked by the likes of the Kardashian-Jenner clan, vitamin gummies have in recent years found popularity among millennials and zoomers, who are more receptive to supplements in the form of “powders, liquids and gummies” than older generations. Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop — no stranger to dubious health trends — sells its own line of such supplements.

On TikTok, influencers who shill multivitamin gummies — and more recently, vitamin patches resembling cutesy, colorful stickers or fine line tattoos — promise glowing skin, lush locks, energy boosts and better sleep. But if it’s real health benefits you’re after, you’re better off saving your pennies.

What does the evidence say about multivitamins?

Photo: AP

The average person can get their recommended intake of vitamins (which have a plant or animal origin, such as vitamin C and vitamin B12) and minerals (elements such as iron, zinc and iodine) from food alone.

“A person who is healthy and has access to a balanced diet, particularly whole foods, generally does not need vitamin supplements,” says Barbara Mintzes, professor of evidence-based pharmaceutical policy at the University of Sydney.

“In almost all cases, people are paying a lot of money for things that are not providing them any benefit at all,” agrees Prof Nial Wheate, director of academic excellence and a medicines researcher at Macquarie University.

Photo: Reuters

Multivitamins contain a variety of vitamins and minerals — experts often quip that they make for very expensive urine.

‘WEE THEM OUT’

“A lot of vitamins are water soluble. So once you’ve saturated your body stores, you just wee them out,” says Clare Collins, a professor of nutrition and dietetics at the University of Newcastle.

While specific supplements are important for conditions linked to nutrient deficiencies (more on this later), for the general population there is scant evidence multivitamins have any health benefits.

Numerous meta-analyses — which analyze results from multiple studies — have found multivitamins do not improve heart health, reduce the risk of certain cancers or make people live longer. An Australian meta-analysis of trials in older adults found multivitamins made no difference to mortality risk.

Collins suspects multivitamins are so popular because they are taken as an insurance policy of sorts because people know they probably don’t eat as healthily as they should.

“Unfortunately, you’re not necessarily getting everything you need [from multivitamins] like dietary fibers and other items … such as phytonutrients, plant-based chemicals that occur naturally in a range of foods.”

In some cases, supplements can do more harm than good. Some fat-soluble vitamins, such as vitamin A, are stored in the liver and can accumulate to dangerous levels if overconsumed, though Collins says this is unlikely to occur from multivitamins.

“Harm tends to come when [people] isolate out just one and take megadoses of that.”

For supplements that purport to have specific benefits — such as hair, skin and nail formulations — Helen Macpherson, a senior research fellow at Deakin University’s Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition, advises wariness about health claims being made.

“Often the ingredients are [in concentrations] just too low to have any physiological benefit,” she says.

Vitamins marketed specifically for hair, skin and nail health often contain biotin, a B vitamin that one review found had “no proven efficacy in hair and nail growth of healthy individuals.” A US study of 176 products marketed as hair, skin and nail supplements found they contained 255 distinct ingredients, including biotin at doses ranging between 100 percent and 33,333 percent of the recommended daily intake. US regulators have repeatedly issued warnings that biotin can interfere with lab tests, giving false results for troponin, a biomarker used to diagnose heart attacks.

In Australia, most multivitamins are regulated by the Therapeutic Goods Administration as “listed” medicines, which have less stringent rules than those classified as “registered” medicines, such as prescription drugs.

“When someone starts a vitamin company, the only thing they have to prove to the government is that it’s safe. They do not have to prove that it works,” Wheate says.

According to Wheate, vitamin patches contain very low concentrations of ingredients, and there’s no guarantee they even work because not all drugs can be delivered through the skin.

And what of gummies sold by Kourtney Kardashian, which supposedly support “vaginal health, freshness and odor?” They “do not add any health benefits for women,” one expert found in a thorough but civil rubbishing.

WHO SHOULD TAKE THEM

In certain cases, there are clear benefits to taking supplements. Vegans, for example, are at higher risk of vitamin B12 deficiency, because it is the only vitamin that humans get exclusively from animal sources — though Collins says it is often added to plant-based milk products.

Iron supplements may be required to prevent or treat iron-deficiency anemia. Likewise, people at higher risk of osteoporosis, such as postmenopausal women, may be advised to take calcium and vitamin D to supplement dietary intake.

Folate, iodine and vitamin D supplements are recommended for pregnant women because they are required for a fetus to develop normally. Vitamin D supplements may also be required for people with darker skin or who don’t get much sun.

And for people with age-related macular degeneration, a combination of zinc and antioxidants known as AREDS2 supplements can reduce the risk of the condition worsening.

“Absolutely there is a place for taking vitamin supplements,” says Macpherson. “Individuals really need to work with their healthcare provider to address those [nutrient deficiencies]. Taking a multivitamin in those cases isn’t going to be sufficient anyway.”

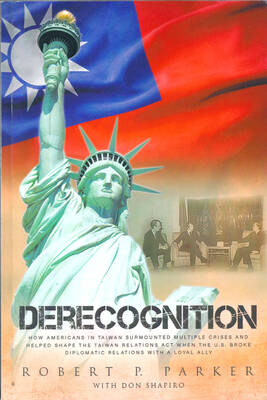

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and