While global attention is finally being focused on the People’s Republic of China (PRC) gray zone aggression against Philippine territory in the South China Sea, at the other end of the PRC’s infamous 9 dash line map, PRC vessels are conducting an identical campaign against Indonesia, most importantly in the Natuna Islands.

The Natunas fall into a gray area: do the dashes at the end of the PRC “cow’s tongue” map include the islands? It’s not clear. Less well known is that they also fall into another gray area. Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) claim and continental shelf claim are not coincident in that area, as Australian security and defense expert Euan Graham pointed out on X (Twitter) last week. “China knows how to exploit a grey zone when it sees one,” he observed.

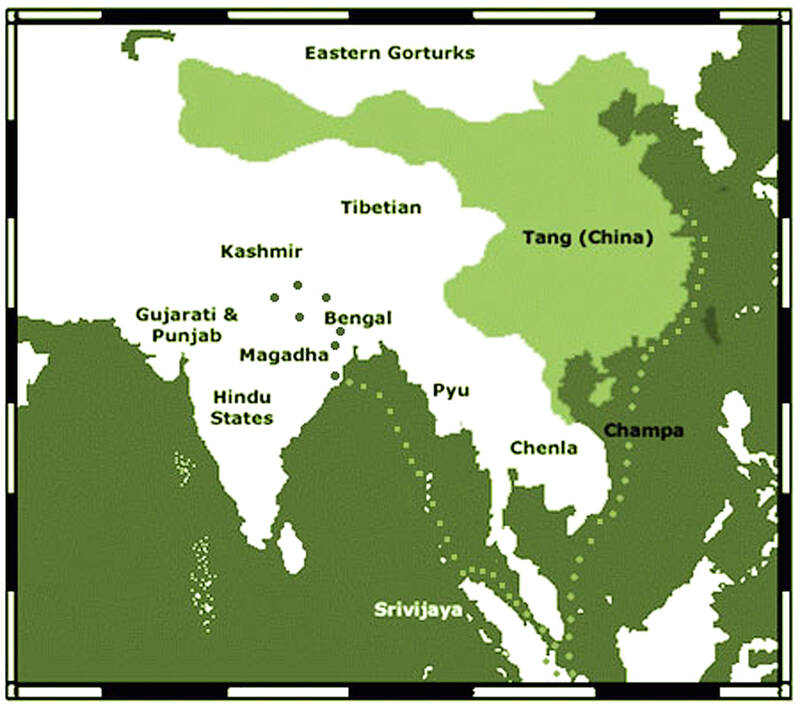

The Natuna Regency, the Indonesian administrative name for the region, contains “at least” 154 islands, 127 of which are uninhabited, according to Wikipedia. As always, after supplying some facts to orient the reader, Wiki then moves on to the history, where, in the very first sentence, we are treated to an amazing nonsense artifact: “The Natuna Islands were discovered by I-Tsing in 671 A.D. and mentioned throughout his notes in A Record of Buddhist Practices Sent Home from the Southern Sea.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

I-Tsing (Yijing, 義淨), was a Tang Dynasty Buddhist scholar whose travel writings are important sources of information on the routes between India, China and the kingdoms of what is today Malaysia and Indonesia. He is famed for translating Buddhist texts, and for his commentaries on the state of Buddhism in the places he visited. He did not, however, “discover” anything. He was a monk, incapable of operating a ship or recording navigational information. The only difference between himself and the cargo aboard the vessels he rode on was that he was alive.

Anyone who wants to see what Wikipedia would be like if PRC propagandists had unlimited access need only visit Quora, which on matters related to the PRC is nigh-on useless, thanks to the 50-cent brigade. But despite Wikipedia’s generally sturdy editing work, pro-PRC statements and frames like this creep in. As the first sentence in the “history” section, it subtly supports the PRC claim to the area by attributing “discovery” to someone from China.

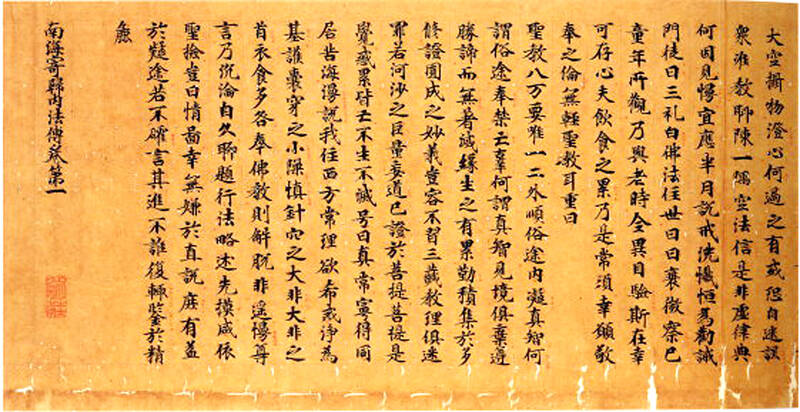

YIJING’S ACCOUNTS

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As history the statement is absurd. Tang-era ships did not play the routes between India, China and southeast Asia. In the seventh century that was the domain of Near Eastern and Indian seafarers who had been part of extensive trade networks across seas of India and southeast Asia for at least a millennium. Yijing himself records that he left from Guangzhou aboard a Persian vessel and sailed to Srivijaya in what is now Indonesia. Along the way he kept running notes on the locations he passed, on their customs and their adherence to Buddhism. It is obvious from both his notes and his occasional references that the islands he passed were inhabited (as many are today).

Yijing’s notes are merely the oldest surviving written account of the area. Since tablets with writing from the Srivijaya kingdom are known from shortly after his time, it is highly plausible that even that state is simply the luck of archaeological practice. Sooner or later earlier inscribed objects discussing the area will be unearthed.

However, there must have been written accounts galore. The loss of so much of the Greco-Roman classical corpus is generally mourned, but the loss of writings from southeast Asia must have been just as great. Yijing records the habits of Buddhist monks wherever he went, describing in minute detail their variations in habits. Buddhism is a text-based religion, and must have been transmitted from literate to literate. With the thousand monks then in residence, Yijing himself extols Srivijaya as an excellent place to study Buddhist texts. All lost, today.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yijing admits he is uncertain of the size of the area, and remarks that the merchants who regularly plied these waters would know. Scholars and dilettantes of our own age tend to focus on the literati of a bygone age, a subtle class solidarity that reaches across time, distorting what it touches. Yet, also lost is another enormous corpus of records: the rutters used by local pilots to navigate.

A rutter is a set of notes a navigator compiles about routes, landmarks, the sea and its currents and tides, the sea bottom, astronomy, climate, wind conditions and other aspects of navigation and port activities. The word in English comes down from Arabic, indicating the importance of Arab rutters in the development of similar western texts. The Persian ship that took Yijing to Indonesia must have had a set of rutters describing the route and its associated land masses in detail, developed over numerous voyages.

HISTORICAL PROPAGANDA

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

These conclusions about Yijing are also true of every other “historical link” invented or appropriated by the PRC for its historical propaganda. The PRC often cites the scribblings of its literati in their travels as legitimating texts for its expansionist claims, appealing to the historical bias that treats literati as a superior source of knowledge. The truth is that the Chinese literati, landlubbers traveling long-established routes, were always the last to know of a place. Centuries before them, the masters of the ships on which they traveled already knew the routes and recorded them in their rutters. Most of these have been lost.

One of the ways our social biases toward the literate and toward history as the story of the upper class help the PRC erase the past is that we forget the existence of documents like rutters, and the non-Han sailors who compiled them (going all the way back to the Austronesians and Negritos who first settled southeast Asia). PRC discourse wants us to focus on the Chinese and their activities, which not only moves them into prominence, but conceals the expert navigators who carried them and their trade goods from one place to another.

Since mid-October a Norwegian survey ship contracted by Indonesia has been in the Natunas performing a fossil fuel survey, and the PRC coast guard has parked a ship there to shadow it. Indonesian navy vessels have been unable to eject the PRC ships and clear the area. Each time the Indonesian authorities have reported ejecting them, the PRC coast guard has returned. As the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) observes, though PRC vessels and the Indonesian coast guard have clashed before, this is the first time the Indonesian government has been so prompt in releasing information on PRC activities.

Expect the Natunas, and Yijing’s name, to come up more often.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.