Angelina Yang thought she knew the Olympic rules — no national flags, no political messages. She was excited to support her compatriot athletes at the Olympics Games in France, where she was living and studying. So the Taiwanese student made what she thought was an uncontroversial sign — the outline of her home island, with the words “jiayou Taiwan” (Go Taiwan) written in Chinese.

But as she unfurled the sign in the stadium stands to watch her team play China in badminton, she was quickly surrounded.

“I was still holding my poster and the security kept talking to his co-worker with his walkie-talkie. After that there was a man, we [think] he’s a Chinese man, he stood in front of me to block the poster.”

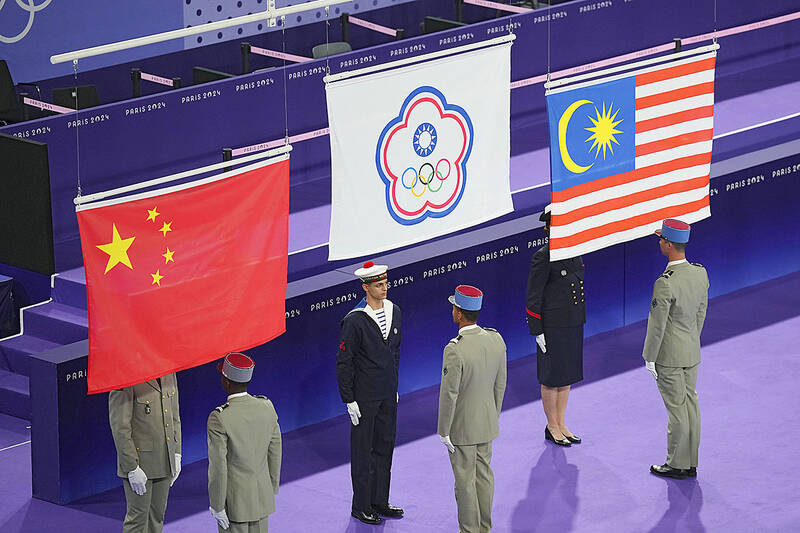

Photo: AFP

The man then ripped it from her hands.

“I was really surprised. And I was really sad and angry at the same time,” Yang said. “We’re not doing anything wrong. Why would we be treated like this?”

Taiwan’s foreign ministry described the incident as violent and against Olympic values of friendship and respect. It has called on French authorities to investigate. In response the International Olympic Committee (IOC) said there were “very clear rules” disallowing banners.

Photo: AP

For decades Olympians from Taiwan — formally the Republic of China — have had to compete under the team name “Chinese Taipei.” The rule is strictly enforced by the IOC.

The rules are often attributed to pressure on the IOC from the Chinese Communist party government, which claims Taiwan as Chinese territory it intends to annex. It uses its hefty influence to shrink as much of Taiwan’s international space as it can, whether that’s at the UN or a birdwatching association.

But the name “Chinese Taipei” also dates back to Taiwan’s former authoritarian rulers, who for decades vied with Beijing to officially represent “China” on the international stage. In 1976 they rejected an offer from the IOC to compete as Team “Taiwan” instead of “Republic of China”. Today, “Team Taiwan” would more accurately represent the population, which increasingly identifies as primarily Taiwanese, but it is no longer an option.

Photo: Reuters

Now, Taiwan is one of just three teams whose flag is banned at the Olympics. The other two are Russia and Belarus — banned as punishment for Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. Under apparent pressure from China, the IOC refuses to let Taiwan enter under its national name. US politicians have described the IOC’s stance as “uniquely irrational”, saying that even if it was commonly accepted that Taiwan was a territory, others — like the British territory of Bermuda, or the US’s Puerto Rico — were allowed to compete under their own name.

The incident was one of several at the Paris Games to spark anger among Taiwanese people over Olympic rules which restrict the ways they can cheer on their national team.

Fans have tried to be creative. One sign at the badminton finals cheered on “bubble tea land”. Another spelled out “Taiwan” with pictures of food. But on the same day Yang’s sign was grabbed, security were pictured confiscating a towel with “Taiwan” written on it. The design incorporated a video review decision from the 2020 Badminton final in Tokyo, which gave Taiwan the gold medal over China. A man wearing a T-shirt with the same design was told to put on a jacket.

Sandy Hsueh (薛雅俶), president of the Taiwanese Association in France, told Taiwan media a blank piece of cardboard had been taken from her by officials who ignored her complaints about nearby Chinese fans having a larger-than-allowed flag. She told CNA she’d been told they had “received an instruction from the Olympic Games saying that anything related to Taiwan or showing Taiwan cannot appear”, and there have been widespread allegations of Chinese nationals pointing out Taiwanese supporters to security.

At Taipei Main Station on Sunday, thousands gathered to watch Taiwan defend and repeat their gold medal win in the men’s badminton doubles. Fans waved the national flag as well as the official “Chinese Taipei” banner. The highly charged match was as thrilling a derby as the 2020 battle in Tokyo.

But it also prompted some sadness, as the medal ceremony raised the IOC-sanctioned flag for “Chinese Taipei”, and a different song, repurposed for the Olympics, played instead of the anthem.

“In some international environments we don’t have a lot of opportunities to say we are Taiwan, so at this time we want to stand up and say ‘we are from Taiwan’,” said Nancy Tung, a 23-year-old student at the station.

For three Taiwanese friends in the crowd, they were more pragmatic.

“We just love Taiwan. Taiwan and Chinese Taipei are still all Taiwan,” said Ivy Shieh, a Taiwanese fan also watching the match.

Yang plans to go to the police, and has support from Taiwan’s representative in France, Wu Chih-chung. “When facing the Chinese team, the IOC will treat Taiwan very harshly,” Wu told Taiwan media. Yang said the current rules are “nonsense” and she hopes they can change soon.

“I hope in the Olympic Games we can support our team just like other people can,” she said. “We follow the rules, but why can’t we bring our own poster that’s neutral and non-political? “That’s all I want, and all I hope Taiwanese people can do.”

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government