To step through the gates of the Lukang Folk Arts Museum (鹿港民俗文物館) is to step back 100 years and experience the opulent side of colonial Taiwan. The beautifully maintained mansion set amid a manicured yard is a prime example of the architecture in vogue among wealthy merchants of the day. To set foot inside the mansion itself is to step even further into the past, into the daily lives of Hokkien settlers under Qing rule in Taiwan. This museum should be on anyone’s must-see list in Lukang (鹿港), whether for its architectural spledor or its cultural value.

The building was commissioned by Lukang native Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮) as a family home in 1913. Already a successful businessman in pre-Japanese Taiwan, he continued to gain prosperity and status after the handover, no doubt aided by his allegiance to the new Japanese rulers. After Japanese troops had captured Keelung and the Republic of Formosa President had fled, it was Koo who opened the gates of Taipei to allow Japanese troops in to establish order. He was subsequently nominated for several official posts, including a position in the Japanese legislature, a first among Taiwanese.

In 1973, Koo’s sons Koo Chen-fu (辜振甫) and Koo Wei-fu (辜偉甫) transformed the mansion into a museum by donating the house and a collection of artifacts, later supplemented by other artifacts from the Koo family and members of the public. The museum has continued to operate up to the present, albeit with several interruptions for restoration work. The carefully selected, high-quality artifacts on display here offer a succinct yet rich overview of life under Qing-ruled Taiwan.

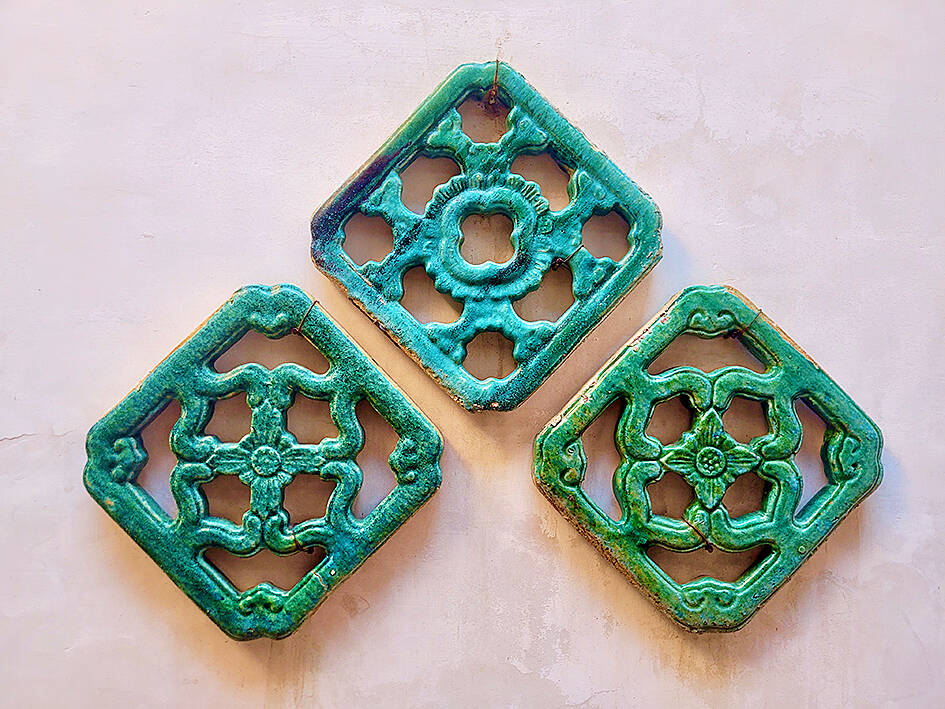

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

AN ARCHITECTURAL FAD

In the early 20th century, many wealthy Taiwanese and overseas Chinese built so-called “Western-style mansions” (洋樓) as both spacious living quarters and symbols of status. These were generally two-story brick buildings with stone accents, often in ornate Baroque style. They sometimes replaced an earlier home, but were sometimes added on to existing Fujian-style dwellings, creating a stark contrast. After the difficult economic times brought on by the war, this style of building fell out of fashion and most of the remaining Western-style mansions in the country are now museums preserved with public funds, or abandoned curiosities slowly deteriorating in the countryside, silent reminders of more prosperous times.

For anyone who appreciates this architectural style, the Lukang Folk Arts Museum is a must-see. The main exhibit hall here, the “Dahe House” (大和大厝), is the most striking example of a Western-style mansion that this author has seen in the country. This is due not so much to the building’s design — which is rivalled or perhaps surpassed by other mansions in Taiwan — but to the immaculate restoration and maintenance carried out on the building and the beautifully manicured grounds surrounding it. As one passes through the gate from the narrow streets of Lukang into the expansive yard, the view of the property is breathtaking.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Dual turrets with black domes flank the main entrance, which boasts Corinthian columns and a red-and-white striped pattern reminiscent of the Presidential Palace. Open-air walkways on both floors with arched openings complete the ornate facade. Attractive paving stone walkways and carefully manicured trees nestled into a spotless green lawn surround the building. Whatever your views on colonialism, it’s hard not to be impressed by the aesthetics of this admittedly very colonial property. Choose a sunny day to visit as the interplay between shadows and light further enhances the crisp geometry of the building.

Off to one side is a more traditional brick building that predates the colonial era, the Ku-Feng Pavilion (古風樓). Unlike the Dahe House, this is a plain brick building with whitewashed interior walls and timber ceilings, just as one can see in traditional three-sided sanheyuan (三合院) dwellings. The first floor is made up of a courtyard and traditional kitchen, while the second floor features a display of two specialized rooms: the nuptial chamber, euphemistically (or perhaps quite literally) termed “hole room” (洞房) in Chinese; and the nursery, including a bed for the new mother and a cradle with mosquito net for the baby.

A WINDOW INTO OLD HOKKIEN CULTURE

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The museum is worth a visit for the architecture alone, but the same could also be said of the artifacts it houses. Through this collection, the Koo family have demonstrated that despite their past association with Japanese colonial powers, they are still fiercely proud of their Hokkien heritage. They have collected and preserved over 6,000 artifacts, displaying just enough of them in the museum to give visitors a broad understanding of the traditional lifestyle of Hokkien settlers in Taiwan, without getting too bogged down in details.

Through simple displays with English and Chinese descriptions, visitors can learn about customs surrounding childbirth, marriage and important festivals. In addition to the fully furnished nuptial room and nursery mentioned above, a few representative items of clothing for important celebrations in excellent condition are on display. Everyday clothing is included in the exhibits, including slippers worn by women who underwent the long-abandoned practice of foot binding. One of the more interesting but obscure artifacts here is an original mold used to make “candy pagodas” — freestanding blocks of sugar in the shape of pagodas or natural objects like flowers and animals — which used to be a common wedding gift to the bride’s family.

The arts are well represented here, too. Sword-swallowing and acrobatics were performed in front of a local temple in the early 1900s, and the actual swords and rings used are on display in the museum. The most popular music styles among Chinese settlers in Qing-era Taiwan were called beiguan (北管) and nanguan (南管). The difference between these two can be imagined after a quick glance at the instruments in their separate display cases. Puppetry — both the glove and the shadow varieties — is represented with a few high-quality exhibits. Painting and calligraphy — art forms for which Lukang was particularly renowned in centuries past — round out this part of the museum.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),