It was Christmas Eve 2024 and 19-year-old Chloe Cheung was lying in bed at home in Leeds when she found out the Chinese authorities had put a bounty on her head. As she scrolled through Instagram looking at festive songs, a stream of messages from old school friends started coming into her phone. Look at the news, they told her.

Media outlets across east Asia were reporting that Cheung, who had just finished her A-levels, had been declared a threat to national security by officials in Hong Kong. There was an offer of HK$1m (NT$3.81 million) to anyone who could assist in her arrest or capture.

News reports included a photograph of her aged 11, seemingly the only picture officials had of her before she and her family left to resettle in the UK in 2020.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“I couldn’t even really recognize myself,” she says.

Cheung says she was still in a state of shock as friends started jokingly congratulating her on her infamy. After finishing school, she had been working as a communications assistant for a campaign group in the UK that advocates for democracy in Hong Kong.

She could barely believe that Chinese officials would care about a teenager living thousands of miles away. Yet, as friends started unfollowing her on social media, the life-changing consequences of what had just happened became clear.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“They were saying ‘sorry, but you are a criminal in Hong Kong now so we can’t be associated with you.’ Even friends here in Leeds said they would have to stop seeing me as they wanted to be able to go back to Hong Kong,” she says.

Cheung had dreamed of a gap year traveling the world and visiting friends in Hong Kong. Neither was possible now, after Chinese officials vowed to “pursue for life” Cheung and others they accuse of promoting democracy. Beijing has a history of targeting critics in exile and pressuring countries to detain and deport them.

“The bounty will follow me for ever. It’s a form of psychological warfare — telling the world that dissent has no safe haven. Even if you were just a teenager when you spoke out, you’re not safe,” Cheung says.

But if China’s aim was to dissuade her from taking a public stance on Hong Kong or criticizing it, it has not worked. Cheung says she has no intention of staying quiet.

Growing up in Hong Kong, Cheung says she always felt patriotic and used to “love running home for the flag-raising ceremony that happened on TV at 6.30pm.” But that all changed in 2019-20 when millions of people too to the streets in Hong Kong.

The demonstrators were protesting against the increasingly autocratic authority of Beijing and the control it wanted to exert over the former British territory, which since 1997 has been classified as a “special administrative region” — part of Chinese territory but governed under separate rules and laws to the mainland.

Until then, Hong Kong had been allowed a degree of autonomy from mainland China, including a partially democratically elected executive and an independent media.

From 2020, after several years of pro-democracy protests known as the “umbrella revolution,” Beijing began to impose closer control over the territory, including changing election laws so that only pro-Beijing “patriots” could run for office, and introducing extradition powers allowing it to transfer fugitives to the mainland.

The constitutional principle of “one country, two systems,” agreed with the British before the handover in 1997, was abandoned, with Hong Kong’s pro-democracy parties later disbanding as the possibility of peaceful political change receded.

“At the time I attended my first protest, I was expecting it to be completely peaceful because I was taught at school that we have freedom of speech and press in Hong Kong,” Cheung recalls.

“Then suddenly, the police started shooting teargas and rubber bullets at us and started arresting people really violently; dragging protesters and standing on their necks. I was just 14 and my worldview completely changed.

“I realized whatever we had been learning in school was a lie,” she says. “I’d been brainwashed. I felt helpless and fooled.”

Taiwan can often feel woefully behind on global trends, from fashion to food, and influences can sometimes feel like the last on the metaphorical bandwagon. In the West, suddenly every burger is being smashed and honey has become “hot” and we’re all drinking orange wine. But it took a good while for a smash burger in Taipei to come across my radar. For the uninitiated, a smash burger is, well, a normal burger patty but smashed flat. Originally, I didn’t understand. Surely the best part of a burger is the thick patty with all the juiciness of the beef, the

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary

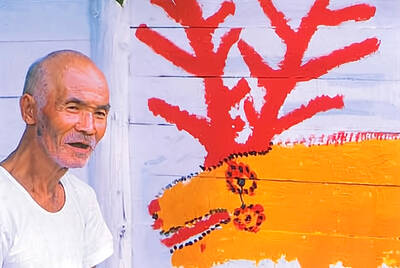

Nov.10 to Nov.16 As he moved a large stone that had fallen from a truck near his field, 65-year-old Lin Yuan (林淵) felt a sudden urge. He fetched his tools and began to carve. The recently retired farmer had been feeling restless after a lifetime of hard labor in Yuchi Township (魚池), Nantou County. His first piece, Stone Fairy Maiden (石仙姑), completed in 1977, was reportedly a representation of his late wife. This version of how Lin began his late-life art career is recorded in Nantou County historian Teng Hsiang-yang’s (鄧相揚) 2009 biography of him. His expressive work eventually caught the attention

This year’s Miss Universe in Thailand has been marred by ugly drama, with allegations of an insult to a beauty queen’s intellect, a walkout by pageant contestants and a tearful tantrum by the host. More than 120 women from across the world have gathered in Thailand, vying to be crowned Miss Universe in a contest considered one of the “big four” of global beauty pageants. But the runup has been dominated by the off-stage antics of the coiffed contestants and their Thai hosts, escalating into a feminist firestorm drawing the attention of Mexico’s president. On Tuesday, Mexican delegate Fatima Bosch staged a