When the writer Fredick King Poole visited Taiwan in the late 1960s, he was struck by “the sad little sun flag over the airport proclaiming this to be China itself, the announcement over the plane’s PA system that picture-taking was not allowed because this island was in fact a great nation at war, the portraits everywhere of poor old discredited Chiang.”

By Chiang, he of course meant Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), then leader of Taiwan’s authoritarian party-state, and the “sad little sun flag” was that of Chiang’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

Poole, who included these satirical digs in his 1971 novel Where Dragons Dwell –– a story of American expatriates grifting off the US military in Bangkok with a backstory set in Taipei –– was one of very few Western authors to offer first-hand accounts of Taiwan during its Martial Law era, which lasted from 1949 to 1987. He was also almost certainly one of the first to write about Taiwan with such streetwise cynicism.

Photo: David Frazier

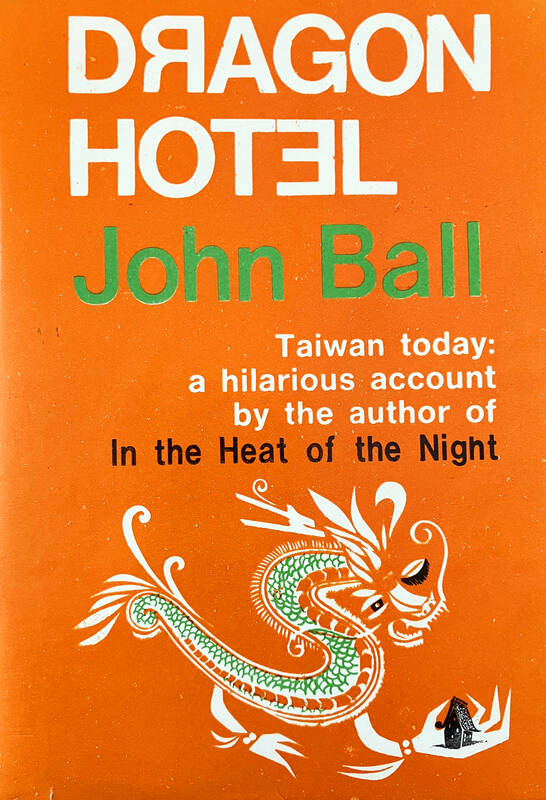

Poole’s novel came as part of a small cluster of three Taiwan books published by two American authors at the height of the Vietnam War era –– a time that saw a large influx of Americans into Taiwan including military and civilians. Two of these books were by Poole, Where Dragons Dwell and a dimestore sex guide called Taipei After Dark. The third was a travelog, Dragon Hotel, by the detective writer John Dudley Ball.

Poole and Ball could not have been more different writers.

Ball was a former US military man who flew the “Hump” during World War II in support of Chiang’s army, and by the time of his Taiwan visit was already famous for his 1965 detective novel In the Heat of the Night, which had been made into a Hollywood film starring Sydney Poitier.

Photos: David Frazier

Poole, the black-sheep scion of an upper crust New England family, was of the 1960s generation, and, though hardly a hippy, was a free-thinking, chain smoking hedonist who professed, “I could not make myself believe in objective journalism.”

‘BLATANT SEX CAPITAL OF ASIA’

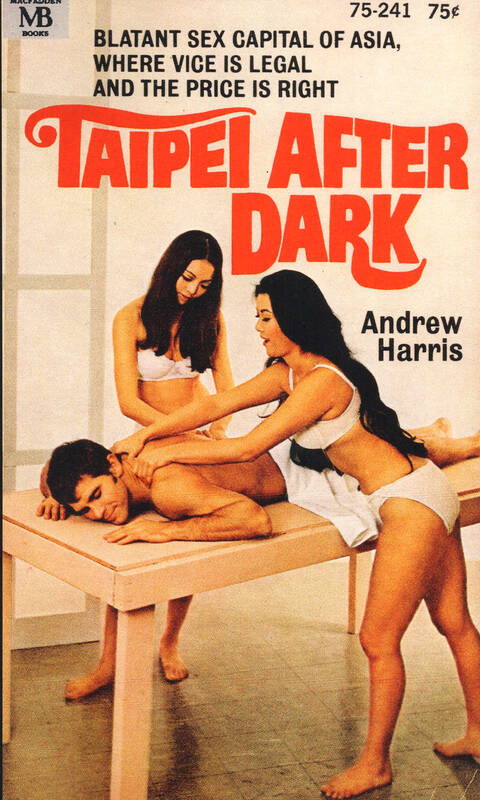

Poole first drifted into Taipei as a sort of gonzo typewriter-for-hire on an assignment to write the semi-factual, soft-core sex guide Taipei After Dark –– a 176-page pocket book sold in American drug stores, which on its cover proclaimed Taipei to be “blatant sex capital of Asia, where vice is legal and the price is right.” It was recently republished in a 50th anniversary edition available on Amazon.com.

Photo: David Frazier

Poole wrote the book under the pseudonym Andrew Harris, with chapters covering massage parlors, girlie bars, hotel sex, gay and lesbian scenes, fantastic orgy scenarios, and a discreet madame said to procure girls for international dignitaries and possess connections in Taipei’s elite corridors of government.

But beyond the sensual fluff, the guide presented an unexpectedly canny summary of Taiwan’s political situation, including several uncomfortable truths. For example, Poole wrote, “It is part of the tragedy of Nationalist China that it attracts the interest of so many small-timers from America,” including “discredited racist Southern senators,” “new-McCarthyite ex-FBI agents,” and smalltown newspapermen who “are treated as press lords if their views are sufficiently to the right.”

In both politics and sex, Poole’s book would likely have scandalized Ball, who arrived in Taiwan on a military cargo plane as a “distinguished guest” of the US Navy.

Permission to visit Taiwan, Ball noted in Dragon Hotel, required a high ranking officer to vouch for him, as “in the embarrassingly recent past another correspondent … had erupted into print with some ‘off the record’ information.”

“Such a violation of journalistic ethics is unheard of,” he continued. “As a result, everyone in the military-information business in Southeast Asia was particularly on edge.”

‘FREE CHINA’

Throughout Dragon Hotel, Ball consistently took the official line of referring to Taiwan as “Free China” or “the real China.” He described his first view of Taiwan from his airplane window, writing, “There, spread out like something created from an armchair traveler’s rich imaginings, was the landscape of China. Steep mountains shot up from the surrounding foundations of brilliantly green fields. Climbing their sides like fantastic water staircases were terraced rice paddies.”

Ball’s purpose for this trip was a Taiwan report, based on visits to Taichung’s CCK Air Base, military installations on the outlying island of Kinmen, the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) headquarters in Taipei and a British military attache.

The Dragon Hotel travelog was probably spun off as a side project. This “real” account centers on Ball’s comedic adventures while staying in a seedy Taipei hotel, where the staff is repeatedly amazed that Ball will not let them supply him with a girl for the night. Or the evening. Or the afternoon.

As Ball wanders Taipei, he captures vivid descriptions of the city, including now demolished landmarks like the Zhonghua Market (中華商場) –– “eight rectangular buildings…built along modern packing-crate lines” indistinguishable save for “big neon advertisements…erected on their roofs”–– and the Jiancheng Roundabout (建成圓環) on Nanjing West Road.

Ball also mentions a Taipei Foreign Correspondents Club –– also long since disappeared –– which featured hotel rooms and a 24-hour bar, where revelers drank till dawn.

Poole, meanwhile, moved in very different, civilian circles. In Where Dragons Dwell, characters frequent one of Taipei’s earliest expat hangouts, a Ximending “basement coffee house called the Barbarian, started two years earlier by a German and an American, now run by an absentee Chinese owner, still the only meeting place for foreigners in town.”

MENAGERIE OF FOREIGNERS

As for its denizens, “the visiting academic experts on Oriental studies all stopped there, as did the young scholars on foundation grants to learn Mandarin, plus the occasional true expatriate scrounging a living teaching, and a scattering of liberal Dutch and Belgian missionary priests.”

But, Poole continued, “Not that their meetings ever led to anything. They always seemed to be on the fringe.”

I recently confirmed the Barbarian was a real place with American journalist Don Shapiro, who first arrived in Taipei in 1969. By email, he noted, “the government shut it down not too long after I arrived as a hotbed of potential opposition.”

The plot of Where Dragons Dwell centers on a trio of expat naifs –– living mostly in Bangkok, but also in Tokyo, Taipei and Laos –– who become unhinged in various ways, until they are finally caught up in a tragic and senseless carbombing precipitated by CIA incompetence.

Poole gave the novel’s main character the name Andrew Harris, which was the very pen name he hid behind in authoring Taipei After Dark just two years previously. The character is almost certainly an alter ego for Poole himself, a 30-something failed US politician who drifts to Bangkok, ostensibly to write a smutty guidebook, but who loses himself in a destructive spiral of whores and alcohol.

The scene that sends Harris to Asia –– a New York job interview –– could well be a novelization of Poole’s own life:

“He remembered the paperback editor, sitting across from him in the anonymity of an East Side businessmen’s restaurant, explaining the work: ‘Don’t worry too much about being accurate. Just sexy…What you’re doing, remember, is basically a girlie book. But don’t forget to get into homosexuality. And for God’s sake don’t forget about lesbians and gigolos. Women buy these books too.’”

“‘If the truth be known,” the editor continues, “the writers don’t count for much in these operations.”

Harris of course takes the job but privately laments that he is writing a “sad hack book…to which he was ashamed to put his name.” The guide, he continues, is “geared presumably to old men who masturbate in Midwestern railway stations.”

Poole’s novel was praised by reviewers as “authentic” and offering “the best physical descriptions of Bangkok we’ve ever seen,” but derided for its “run-of-the-mill” story and characters who “never acquire substance.”

Though Where Dragons Dwell was published by literary-minded Harper’s Magazine Press, following poor reviews, paperback rights were quickly handed to sci-fi publisher Berkley Medallion, whose catalog included Frank Herbert’s Dune and titles by Robert Heinlein. There it was miscast as a dimestore thriller, with a caption added to the cover: “American adventurers find sensuality and deadly danger in mysterious Bangkok.”

It was too bad they tried to peg Poole as another James Clavell. They’d have done better to call him Asia’s Henry Miller.

PERSONAL FREEDOM

For me, the most enduring quality of Where Dragons Dwell is how it predicts the waves of Western expats who would follow the US military presence in Asia. Several remarkable passages describe the expat’s sense of awakening to personal freedom, including the realization of one female character, a flighty Bennington college dropout who drifts to Bangkok by way of Tokyo and Taipei.

In Asia, “She had not needed the years she thought were required to make contacts in New York, the linguistic and cultural jump that would have had to precede triumph in Paris, the studied calm necessary to movement in London. She leapfrogged the cities of the past.”

And once quickly established, “She was a singer who had found her voice, a starving child who had come upon food….The best that her own past had had to offer did not approach what was now in her grasp. Nobody’s dictates now governed her life.”

Following the failure of Where Dragons Dwell, Poole carried on in journeyman fashion, writing After Dark sex guides to Bangkok and Manila while at the same time authoring Asian-themed hardcover nonfiction for American high school libraries. In 1984, he finally co-authored a critically acclaimed book of investigative journalism, Revolution in the Philippines: The United States in a Hall of Cracked Mirrors, before eventually returning to the US to run “authentic writing” workshops in New Hampshire.

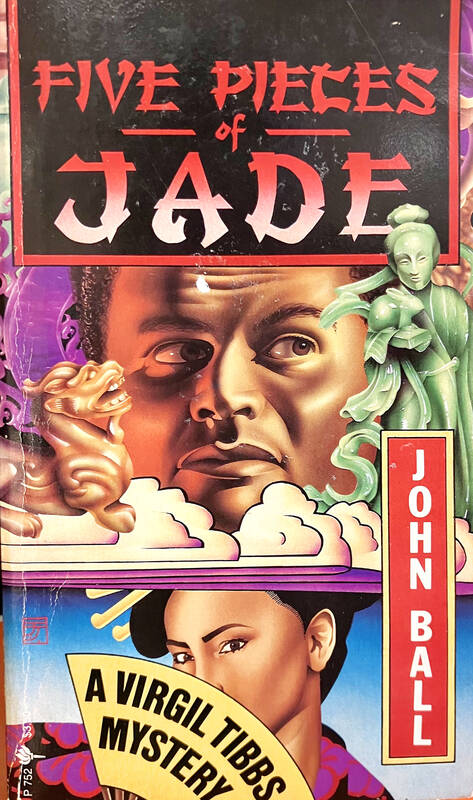

Ball was the more commercially viable of the two. He enjoyed consistent success with his Virgil Tibbs detective novels, many of them relying heavily on Asian story elements. His 1972 novel, Five Pieces of Jade, might even be construed as anticipating the current fentanyl crisis, as it involved a Chinese plot to flood the US with a synthetic opioid stronger than heroin. As the book however centered around the murder of a Chinese American man in California, it was reprinted in 1985, a year after the real-life Daly, California murder of Taiwanese dissident writer Henry Liu (劉宜良). But Liu of course was killed by KMT agents sent from Taiwan, while Ball could only ever imagine his fictional bad guys as being communist Chinese.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on