March 18 to March 24

Yasushi Noro knew that it was not the right time to scale Hehuan Mountain (合歡). It was March 1913 and the weather was still bitingly cold at high altitudes. But he knew he couldn’t afford to wait, either.

Launched in 1910, the Japanese colonial government’s “five year plan to govern the savages” was going well. After numerous bloody battles, they had subdued almost all of the indigenous peoples in northeastern Taiwan, save for the Truku who held strong to their territory around the Liwu River (立霧溪) and Mugua River (木瓜溪) basins in today’s Hualien County (花蓮).

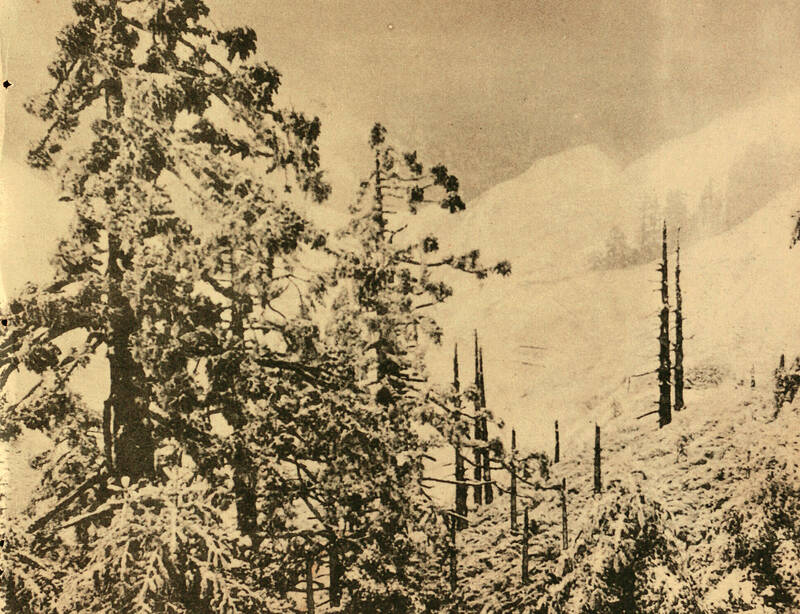

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The Japanese forces were somewhat familiar with lowland terrain, but even after 17 years of ruling Taiwan, they knew nothing of the Truku areas. After several failed survey attempts, time was running out with orders to complete the plan within the allotted time frame.

After praying at the Taiwan Shinto Shrine in Taipei, Noro, who was the expedition’s chief surveyor, led the 286-strong team from Nantou County’s Puli Township (埔里) toward the high mountains of the north.

It was a disaster. After scaling the peak, the group’s camp was pummeled by a massive storm that brought wind, rain and even marble-sized hail. The official death toll was 89 — all of them Taiwanese.

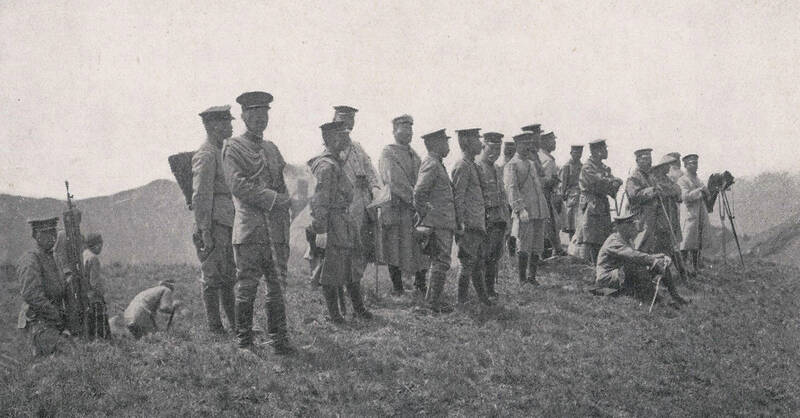

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Even though the Yasushi Noro Incident remains the deadliest mountaineering disaster in Taiwan’s history, remarkably, Noro was rewarded as there were no Japanese casualties.

He tried again in October and succeeded, paving the way for the 1914 Truku War.

MAPPING INDIGENOUS LAND

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Noro first arrived in Taiwan in 1899 as a survey technician. By 1902, he was supervising land surveying operations across the entire island. After assuming his post in 1906, new governor-general Samata Sakuma vowed to bring the remaining hostile indigenous areas under colonial control, as they contained valuable timber and camphor resources the Japanese hoped to exploit.

Noro worked directly under Sakuma in the Indigenous Affairs Agency. His first official expedition to indigenous lands was in November 1908, when they scaled Niitaka Mountain, known today as Yushan or Jade Mountain (玉山). It was during this trip that the Japanese realized Yushan belonged to a separate mountain range from the Central Mountain Range.

Noro first attempted to survey Hehuan Mountain in 1910, but turned back due to a storm. Another team led by police officers investigated the Liwu River basin in December 1911. But halfway into the journey they encountered about 40 Truku warriors who blocked their way. Since they were not familiar with the area, the Japanese opted to retreat.

In September 1912, a team climbed Nenggao Mountain (能高) and recorded the Truku villages along the eastern part of Mugua River and the paths the inhabitants used to traverse the thick forest. Then, they climbed the main peak of Chilai Mountain (奇萊山) and mapped the surrounding landscape.

However, they were stopped from going further east by representatives of the Butulan group of Truku, who refused to negotiate or allow the Japanese to meet their village chiefs.

PRECARIOUS ASCENT

The expedition set out in March 1913. It included 14 Japanese officers, 55 Japanese patrolmen and 64 indigenous guides as well as Han Taiwanese porters and frontier guards. The indigenous guides were led by Katsuzaburo Kondo, who moved to Puli in 1896 to trade with the indigenous Seediq and married the daughter of a local chief. In the early days, when few Japanese dared venture into hostile indigenous territory, Kondo was accepted into Seediq society and often acted as the main go-between for the government and different indigenous groups.

They had just reached Yingfeng (櫻峰) police station west of Hehuan Mountain on March 17, when it began to pour. They were forced to camp in the station for two days, and about 40 to 50 porters and frontier guards could no longer stand the cold and slipped away during the night.

The sky cleared on March 20, and porters arrived with fresh supplies. Unfortunately, these porters were forced to join the march up the mountain to replace those who fled, despite them not wearing the proper clothing.

Around noon the next day, the indigenous vanguards sent word that it was extremely cold and snowy on the main peak and advised the group to seek shelter in a forest on the side of the east peak. Kondo personally headed back to convince Noro, but Noro insisted on camping on the top. He was worried that the Truku would attack them in the forest, and preferred to stay on the peak where visibility was better.

Both sides refused to budge, and in the end Noro allowed the indigenous team to stay in the forest and meet them on the peak the following morning. Noro’s group reached the top by 4pm and set up camp.

DEADLY WINDS

They barely had an hour to rest.

The northeastern wind had been increasing in force under pressure as it traversed the narrow Liwu River valley up Hehuan Mountain. Upon reaching the top, with no barriers on either side, it exploded exponentially, hitting the camp with full force.

The entire campsite was destroyed, the team members futilely resisting the elements with soaking wet blankets. Then the hail started falling, and the temperature fell below zero. Most of the Han Taiwanese came from the plains and had never experienced such cold before, faring visibly worse than the Japanese. Many tried to flee in the dark despite Noro’s attempt to stop them.

The storm lasted until dawn. Between 50 and 60 people were missing, and they had lost everything except for the surveying equipment. Noro had no choice but to call off the expedition.

As the survivors descended, they found bodies scattered along the path, belonging to those who tried to leave during the night. A dozen fortunate ones were rescued by the indigenous team. More collapsed along the way.

Upon returning, Noro asked to be punished, but he was rewarded for “responding appropriately during disaster and safeguarding the lives of the team’s members.” Apparently, only Japanese souls counted.

Rescuers were able to retrieve 34 bodies. The victims’ families were compensated, but no plaque was erected and their names remain unknown.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name